Wearables Exhibition Spotlights Intimacy and One-Off Economics

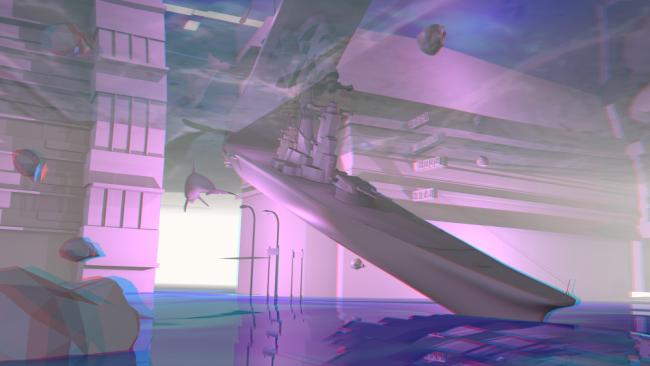

Three baby sweaters joining imaginary hands are tacked to the wall of a gallery in central Copenhagen. Nearby, a nondescript white baseball cap dumps a steady stream of water into an absorbent mesh cylinder, while a tent with long, billowing sleeves for arms and legs makes itself known as the only Coronavirus-approved design object in the room, a technicolor “disaster kit” offered nearby for additional security. Across the room, a teddy bear family inhabiting CFGNY’s hot pink mesh gown is poised for escape upon handling. (Here, like in any self-respecting fashion establishment, touching is encouraged).

-

Tent and disaster kits by Lucy + Jorge Orta, part of Wearables at Étage Projects. Photo by Robert Damisch

-

Wearables curated by Jeppe Ugelvig in on view at Étage Projects January 28 to March 28, 2020. Photo by Robert Damisch

-

Wearables includes a hot pink dress with teddy bears by CFGNY. Photo by Robert Damisch

Strung along rails and suspended off hangers under flattering gallery spotlights, these are clothes, in the sense that they approximate, to a greater or lesser degree, the human form. And for the most part, they definitely feel like clothes; made from recognizable fabrics, the jeans, shirts, and scarves are in turns squishy, scratchy, smooth, or sticky — depending on what you grab. But they’re also at once wearable sculpture, affordable art, and functional design, forecasting a viable future for fashion production in an increasingly commercialized and casualized creative labor landscape.

“There is a long but scattered history of clothing made by artists,” explains Jeppe Ugelvig, the curator of Wearables, running through March 28 at Étage Projects. Ugelvig is the author of Fashion Work 1993-2018: 25 Years of Art in Fashion, which traces a quarter-century history of artists occupying the fashion industry. Selecting 23 artists and collectives whose practices slip fluidly among art, design, and fashion — many of whom are part of Étage’s roster — Ugelvig presents a show that sits between a store and gallery, presenting objects and wearables that are born out of a studio setting logic. “We wanted to embrace the spatial experience of the shop as an exhibition format,” explains Ugelvig, “But also have a very sensory and available component — trying things on, touching things, bringing a level of intimacy to the experience.”

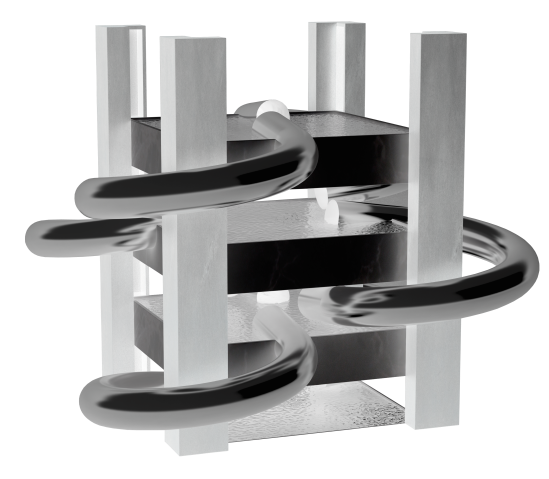

For Ugelvig, it was important that the exhibition presents a broad range of practices, so it stays light on its feet and avoids hierarchical distinction. Artists Lucy + Jorge Orta (who are behind the aforementioned tent and disaster kits) appear alongside a drunken banana-hued bikini by fashion designer Sinéad O’Dwyer. The maker of the baby sweater, artist Victoria Colmegna, has worked previously in fashion but this was her first experience outsourcing knitting jobs. Design duo Soft Baroque’s collection of accessories riff on a PoMo pastiche of brick, wood, and stone CGI finishes, taking their super-sensory design aesthetic to the realm of wearables for the first time; the feeling of a brick-patterned scarf on skin is squirmy, alien and thoroughly bodily.

-

Wearables curated by Jeppe Ugelvig in on view at Étage Projects January 28 to March 28, 2020. Photo by Robert Damisch

-

Wearables curated by Jeppe Ugelvig in on view at Étage Projects January 28 to March 28, 2020. Photo by Robert Damisch

-

Wearables curated by Jeppe Ugelvig in on view at Étage Projects January 28 to March 28, 2020. Photo by Robert Damisch

“Reification is central to the whole mythology of art, whereas fashion is inherently about the everyday — even if it’s expensive,” says Ugelvig. In a sense, an object’s wearability grounds it through functionality and a direct relationship with the body, while the format of a one-off wearable hits a sweet spot between affordability and a collectible artist’s original.

While contemporary art tries its best to muddy the origin story and trade routes of its material process, resulting in many zeros being added between the artists’ production of the work, it sitting in a Swiss shipping container for 10 years, and its final sale price at auction, fashion insists on addressing how objects circulate in real time as cultural commodities. In other words, it can teach art a lot about affordability and access — and about bridging the topic of finance between artist and gallerist — a conversation that former is often left out of. “It was super important to discuss pricing with the artists and the gallerist, asking what we hope to achieve in terms of sales,” recounts Ugelvig. Curious how this model of transparency looks on the fashion side of the fence, I ask Ugelvig about the exhibition’s opening reception, staged during Copenhagen Fashion Week. “It was packed with art and fashion students,” he shares. “They are all seeking) out new models and new scales of production. In an industry that has a history of marginalizing practices that don’t sit neatly in categories, it’s important for the next generation of designers to ask, how can you make a living doing what you’re doing.”

Text by Alice Bucknell.

Installation photography by Robert Damisch. Courtesy Etage Projects.