Big Ideas Economically Realized At The Lisbon Architecture Triennale

“Architecture is based in a type of rationality that is not Cartesian,” declares architect and educator Éric Lapierre, chief curator of the 2019 Lisbon Architecture Trienniale, which he has titled The Poetics of Reason. “In architecture, one and one don’t make two, but three at least. Architecture is an added value… that goes beyond simply producing a functional building.” And this, in a nutshell, is the key to deciphering the very rich and varied offer put on by the triennial team — all of whom teach under Lapierre at the École d’architecture de la ville et des territoires Paris-Est — which takes the form of five exhibitions displayed at sites all over the Portuguese capital this fall.

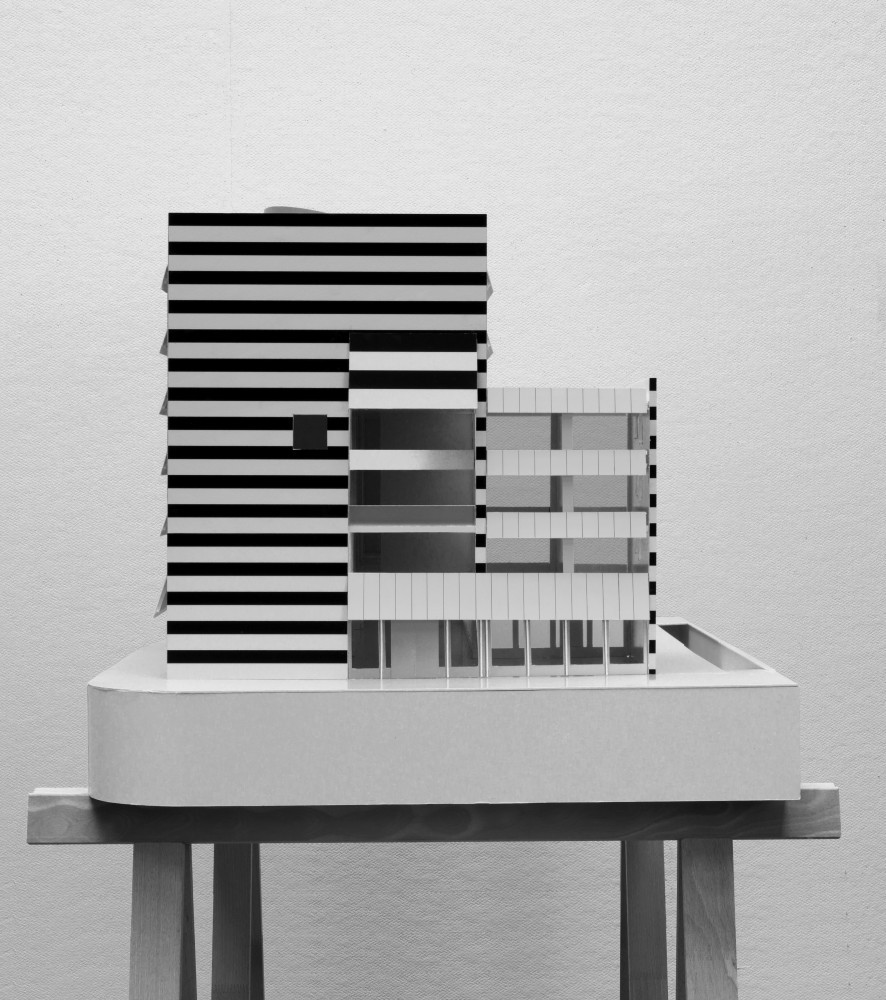

The principal exhibition, curated by Lapierre himself, is being shown in a former power station in Belém that now forms part of Lisbon’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. Entitled Economy of Means, it sets out to demonstrate how constraints and limitations can stimulate creativity, producing a poetics that is assimilable to poetry itself, an art which (epics aside) is often about making very little do an awful lot, whole worlds being evoked in just a few lines. Given this subject matter, the onus was on the curatorial team to make the exhibition itself a demonstration of a certain economy of means. And it has to be said that they’ve pulled the rabbit out of the hat with a certain flourish.

-

Installation view of Economy of Means. Photography by Fabio Cunha.

-

Installation view of Economy of Means. Photography by Fabio Cunha.

-

Installation view of Economy of Means. Photography by Fabio Cunha.

One of their accomplishments is making, without much of a budget, an interactive installation that meditates on the relationship between typology and architecture. Typology — “a kind of matrix repeated during a long time whose reinterpretation allows the creation of an infinity of solutions,” as the wall text puts it, is set in opposition to architecture as “mere invention” intended solely to astonish. To suggest this the curators papered a giant wall with small-scale printouts of type plans and suspended binoculars from the ceiling so that visitors can zoom in, birds’-eye style, on this city of archetypes. “The economy of void” is another of the exhibition’s themes — spaces of congregation, from churches to town halls to trade-fair complexes that require very wide spans so as to accommodate large gatherings in ideal conditions (paradoxically not always the most structurally economical building type). Faced with the impossibility of bringing these spaces to the show (the eternal problem of architecture exhibitions), the curators laid the buildings' printed-out floor plans on the ground, suspended their roof plans from the ceiling, and let visitors’ imaginations take flight from where they stand in between. And making that room work even harder, they filled one entire wall with a reproduction of René Magritte’s 1959 La Chambre d’écoute (a canvas depicting a giant green apple completely filling the volume of a bedroom). You only catch partial glimpses when in the room itself but can contemplate the image in full through a tiny hole cut into the wall of an upper level room dedicated to the theme of “small is meaningful” — a section that includes a house by Kazuyo Sejima whose bedrooms are “reduced to the size of the beds.” (Claudia Mion and Sophie Dulau are behind the exhibition’s ingenious scenography which does so much more with so very little.)

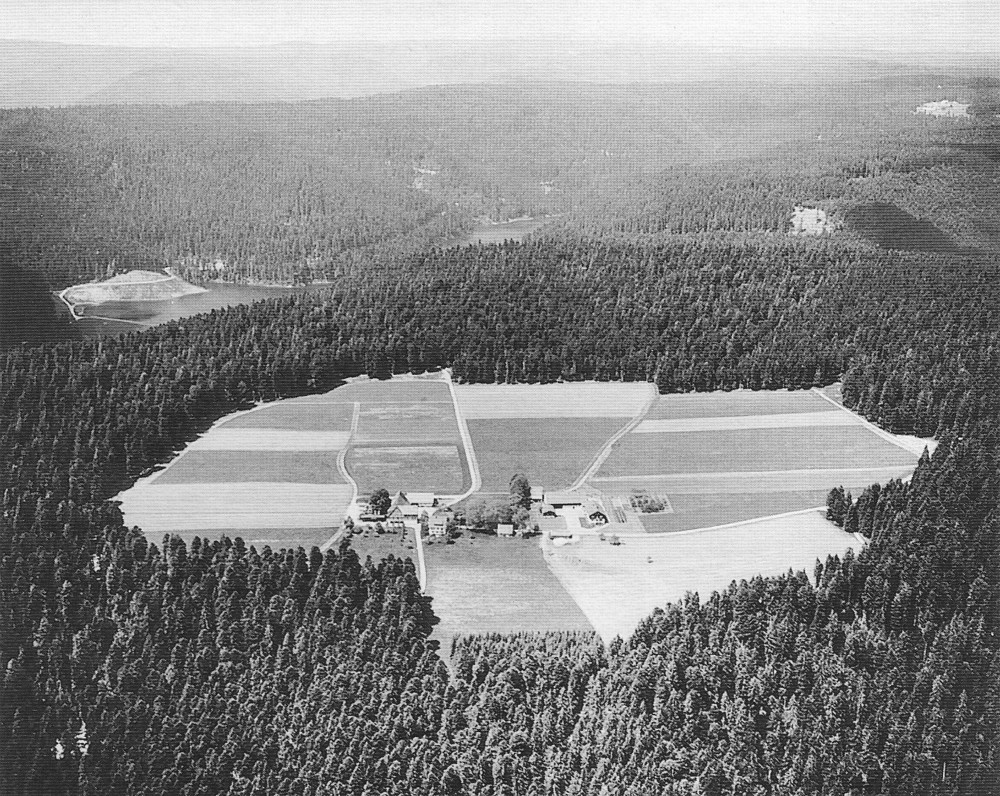

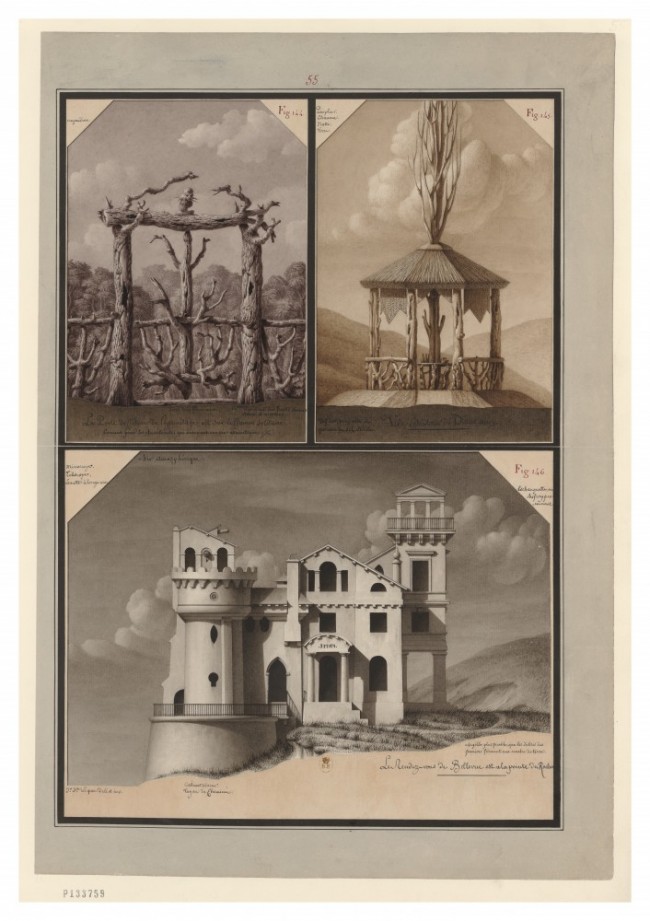

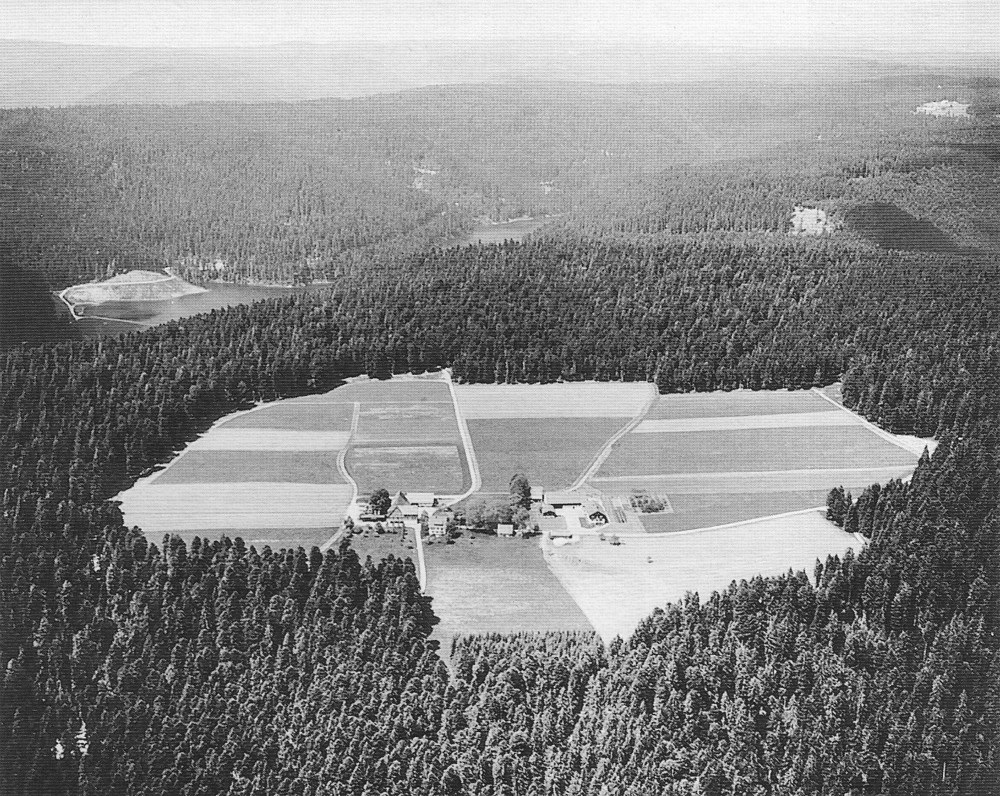

Meanwhile, just up the road at the Garagem Sul, scenography was pretty much entirely absent from philosopher and historian Sébastien Marot’s exhibition Taking the Country’s Side: Agriculture and Architecture. Like Philip Johnson pipping Mies to the post with his Glass House, Marot has got this one in just before Rem Koolhaas’s big countryside show opens at New York’s Guggenheim in February. But where OMA will enjoy big Guggenheim bucks, Marot, as he pointed out at the opening, had just 60,000 euros (as, indeed, did all the other curators at the triennial) to fill 2,000 square meters of former underground car park. His solution, for an exhibition overflowing with ideas, was that old classic of sticking a book up on the wall, or in this case hanging it from the ceiling since walls are on the scarce side in the Garagem.

-

Clairière Culturale. Courtesy Wladyslaw Sojka.

Agriculture and Architecture

-

Agriculture and Architecture: Joel Sternfeld, McLean, Virginia, December 1978. © Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

There’s little need to bother with the show at all since Marot has also produced an actual book to accompany it, a handy pocket edition that’s perfect for the subway or the john and allows you to dip at bite-sized leisure into a fascinating compendium of information. “The basic hypothesis of this book and exhibition,” writes Marot in his introduction, “is that no sound reasoning will develop on the future of agriculture and architecture, which both emerged as the twin fairies of the Neolithic revolution (and thereafter of the Anthropocene), unless those two fields of concerns, and their associated modes of living, are reconnected and fundamentally rethought in conjunction with one another.” Covering everything from the arrival of orthogonal architecture in the Neolithic period to the rise of agrochemistry and mechanization thanks to the 20th century’s world wars, not to mention the emergence of ideas of sustainable permaculture in the post-war era, it forms what Marot describes as “a treasure trove of ideas and principles that significantly challenge the core concepts of architecture and urbanism today... a poetics of reason for the Anthropocene.” The only unconvincing note was the rather hastily drawn potential future scenarios at the end of the show — to be taken seriously they would have needed a whole exhibition to themselves.

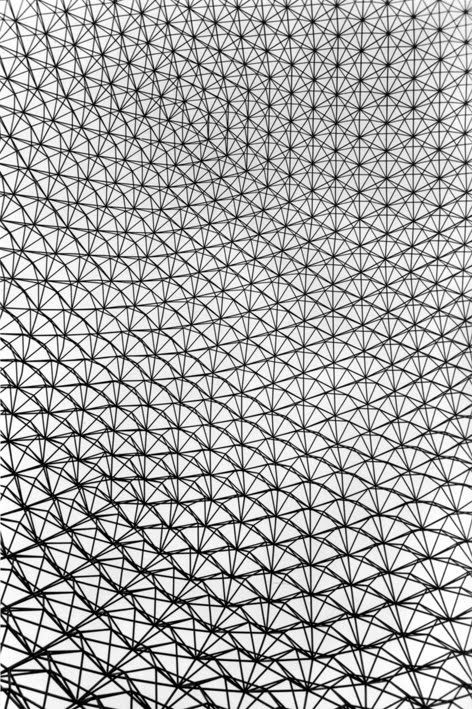

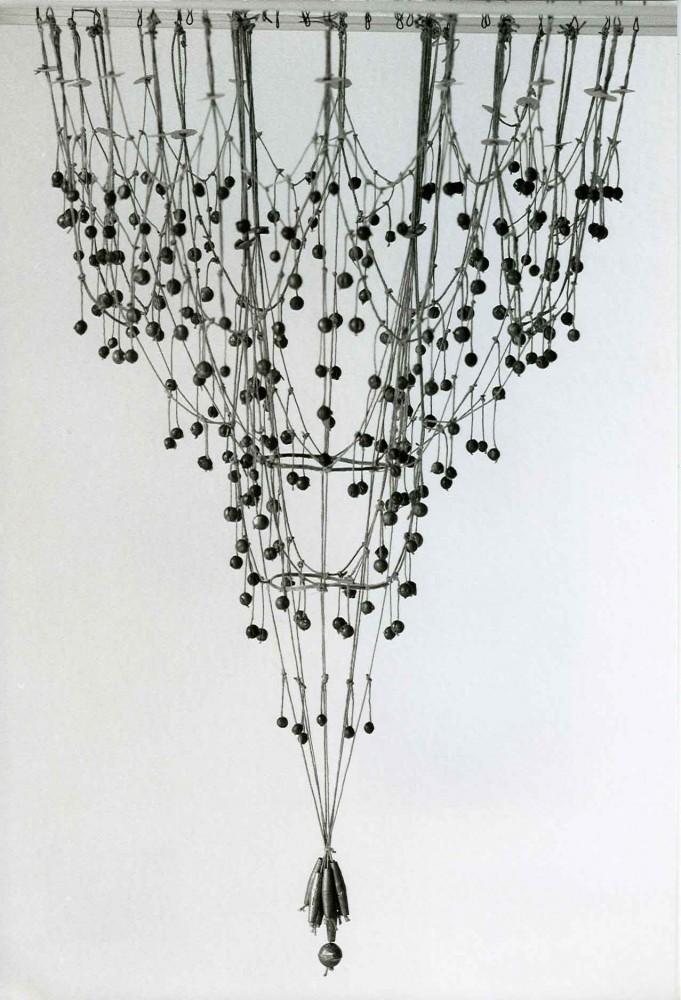

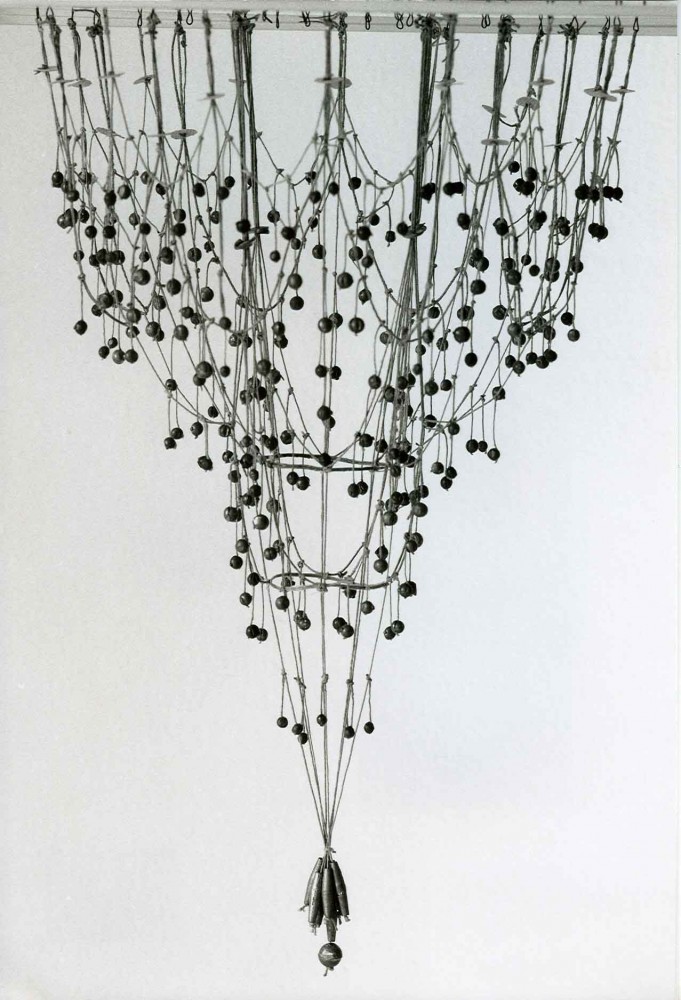

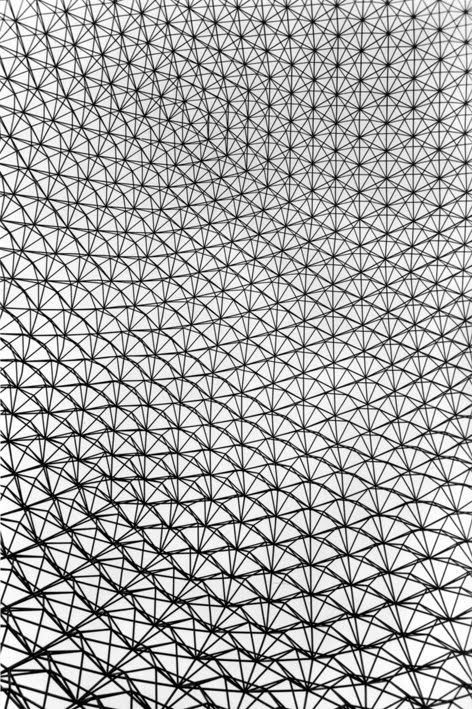

A similarly rather literal economy of museological means is in operation in Lisbon’s old town at the 18th-century Palácio Sinel de Cordes where Natural Beauty: Meanings of Construction has been put on by Laurent Esmilaire and Tristan Chadney. Here the theme is a poetics of construction, demonstrated through photographs of buildings such as Buckminster Fuller’s Biosphere, Édouard Albert’s Tour Croulebarbe in Paris, or OMA’s Maison à Bordeaux, as well as one of the string-and-weights models developed by Gaudí to develop materially minimalistic self-supporting vault systems. “By natural beauty,” write the curators, “we mean the inherent harmony and coherence of an artifact that transforms it into a structured organism, where all parts are linked to one another in highly interdependent relations, from the parts to the whole and from the whole to the parts.” In this reading of the poetics of the economy of means, the structural and the decorative become one, and it could thus legitimately have been included in the fourth of the triennial’s exhibitions, What is Ornament?

-

Gaudí model in Natural Beauty.

-

Natural Beauty: Detail of Richard Buckminster Fuller, Biosphere – formerly US Pavilion for Expo 67, International and Universal Exposition, Montreal, Quebec – Canada, 1965–1967.

This study of ornament is shown on the other side of town at Culturgest — the cultural arm of the Caixa Geral de Depósitos, which is housed in a striking example of Portuguese PoMo by Arsénio Cordeiro (a building that probably wouldn’t have made it into the triennial curators’ canon of reason, even if its façade structure and decoration are one and the same thing). Here scenography is crucial. Brussels-based artist Richard Venlet was called in to turn Culturgest’s giant ground-floor hall into a series of spaces that curators Ambra Fabi and Giovanni Piovene have filled with a thematic dissection of ornament into six categories: moldings, columns, walls, patterns, vessels, and fireworks (the latter being the idea of ornament as applied to the city at a macro scale). More than a century after Adolf Loos’s Ornament and Crime, say the curators, “the discussion about ornament is far from settled… Today it seems natural to investigate the contemporary form and proportion of a column; to carefully consider the junctions among elements; to question the nature of cladding, as a project rather than as a consequence; to design expressive façades with images and typography; and to dress surfaces with patterns, motifs, textures, materials, and colors.” All sorts of examples are provided in various forms — drawings and photographs of course, but also actual bits of façade, column, and moldings — as well as a British contribution from architect Sam Jacob and writer and curator Priya Khanchandani entitled Pattern as Politics, for which 15 artists, designers, and architects were asked to create work responding to Owen Jones’s influential 1856 book The Grammar of Ornament. Published at the height of British imperialism, according to the curators, the tome “flattens histories and cultures through its categorizations,” employing “disparaging language about nations that were colonized by the West.” Here the problematic nature of appropriation is addressed. “Our project attempts to remarry the decorative and symbolic strands of pattern making,” explains Jacob, “and in so doing aims to reveal that politics, as much as pleasure, is central to the design of pattern.”

Inner Space: George Bailey, View of Various Architectural Subjects belonging to John Soane Esq. R. A. as arranged in May MDCCCX, c.1811. © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

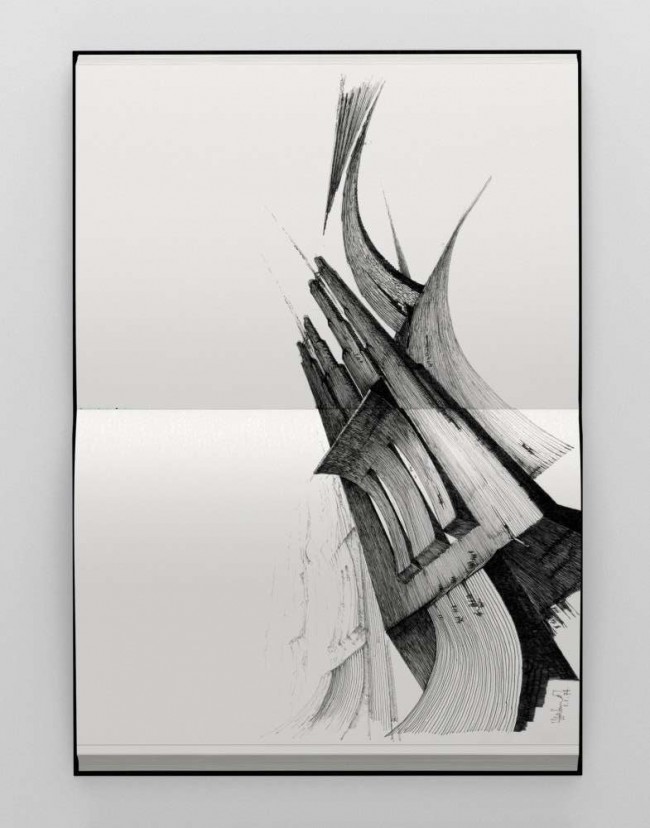

Of the five triennial shows, critics have been unanimous in praising Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli’s Inner Space, at the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado, as the most accomplished. But the Italian duo arguably had the easiest time of it where the business of putting on an exhibition is concerned since their chosen subject — “the dialectical confrontation between creative imagination and rational thought” and the “different ways the cognitive process of imagination takes place and how it gets transformed into an architectural work” — naturally expresses itself in media that fit very happily into a gallery context. This is not to diminish the intelligence of Fabrizi and Lucarelli’s approach, however, which explores themes ranging from mapping and musées imaginaires to monuments and cyberspace. You’ll find everything here from George Bailey’s 1811 section of Sir John Soane’s house — “the most notable example of a Wunderkammer built by an architect” — or a model of Wittgenstein’s Norwegian hut, an “enhancer of the philosopher’s thought” — to Ustwo Games’ Monument Valley I and II, video adventures that stage “impossible spatial configurations” in a range of styles “from ancient monuments to brutalist architecture” — or The Landlord’s Game (1904), a precursor to Monopoly. There’s mapping and digital documentation by Forensic Architecture, classics such as Vriesendorp and Koolhaas’s 1972 The City of the Captive Globe, and countless pieces by artists, including Grayson Perry’s 2013 A Map of Days, “a self-portrait of the artist in the form of a fortified town.” The ultimate space-ideas machine on show is perhaps Giulio Camillo Delminio’s 16th-century Theatre of Memory, which takes Cicero et al.’s “method of loci” or “mind palace technique” for rhetorical speaking and attempts to use it to archive all human knowledge in a building layout based on Vitruvius’s description of a Roman theater in De Architectura.

-

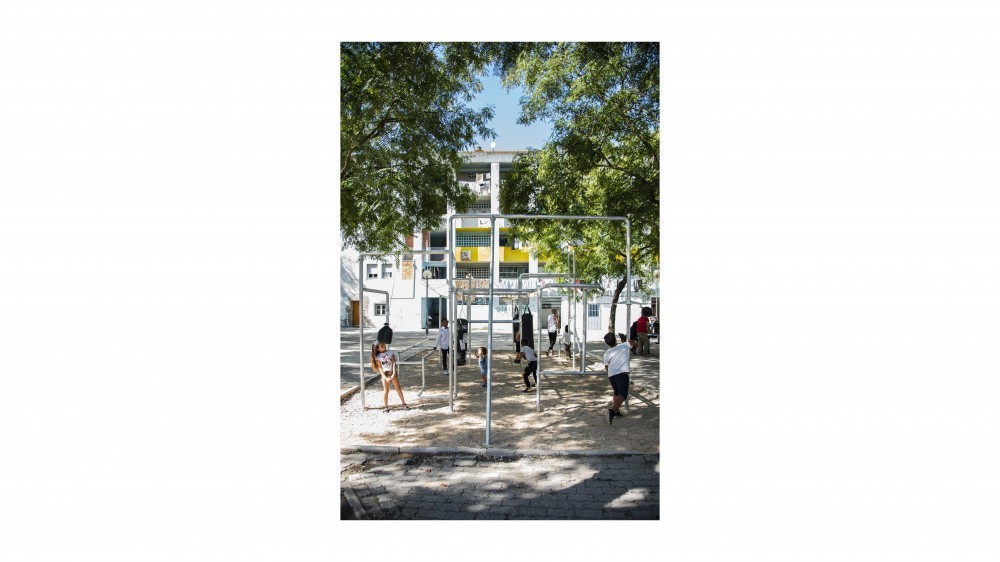

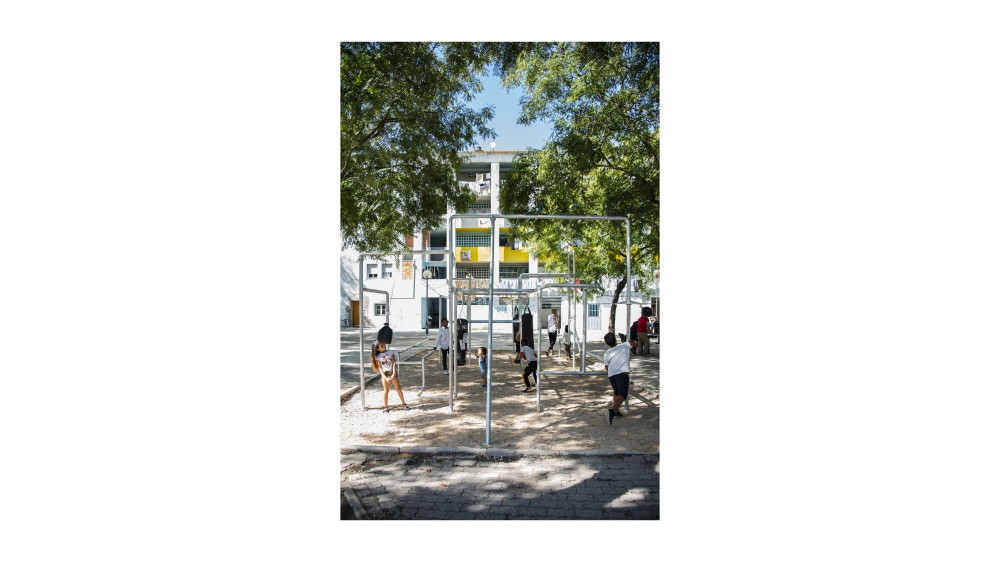

Daniel de Léon Languré, Boxing Boxes (2019).

-

Daniel de Léon Languré, Boxing Boxes (2019). © Hugo David

-

Daniel de Léon Languré, Boxing Boxes (2019). © Hugo David

In addition to the five big shows, there were many ancillary events and installations at the triennial — far too many to list here. But one in particular stood out, since it perfectly illustrates the overall theme. In a crumbling housing project out at Olaias which, due to an administrative anomaly, has essentially been abandoned to the care of its impoverished inhabitants for the past 30 years, Mexican architect Daniel De León Languré has installed Boxing Boxes, a sort of jungle gym made out of welded scaffolding poles from which various sizes of punching bags have been suspended at different heights. Whatever one’s feelings about boxing as a sport — for De León it’s “a tool of self-discipline” that “channels violence” to become “part of the civilizing process” — there’s no denying that the installation has been an instant hit with kids of all ages living at the housing project, who have absolutely no other play facilities on offer. Built for a mere 6,000 euros, it elegantly, economically, and radically transforms the courtyard where it stands through what De León describes as an act of “urban acupuncture.” A simple yet highly effective poetics of reason, it proves that in architecture two plus two can indeed make rather more than just four.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Installation photography by Fabio Cunha and Hugo David.