Lina Bo Bardi's Glass House

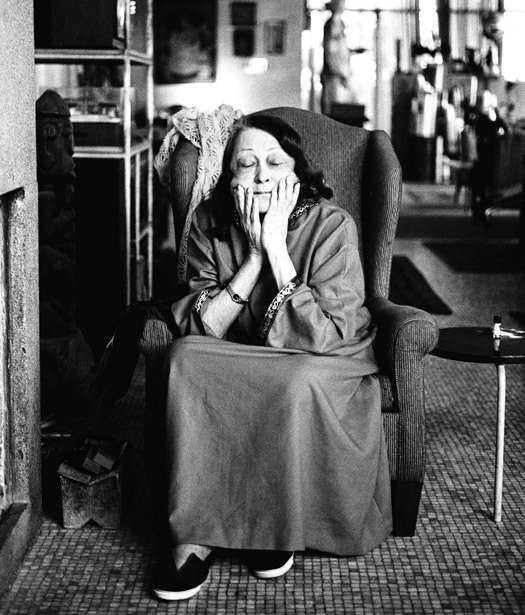

Portrait of Lina Bo Bardi (1914–92) by Juan Esteves.

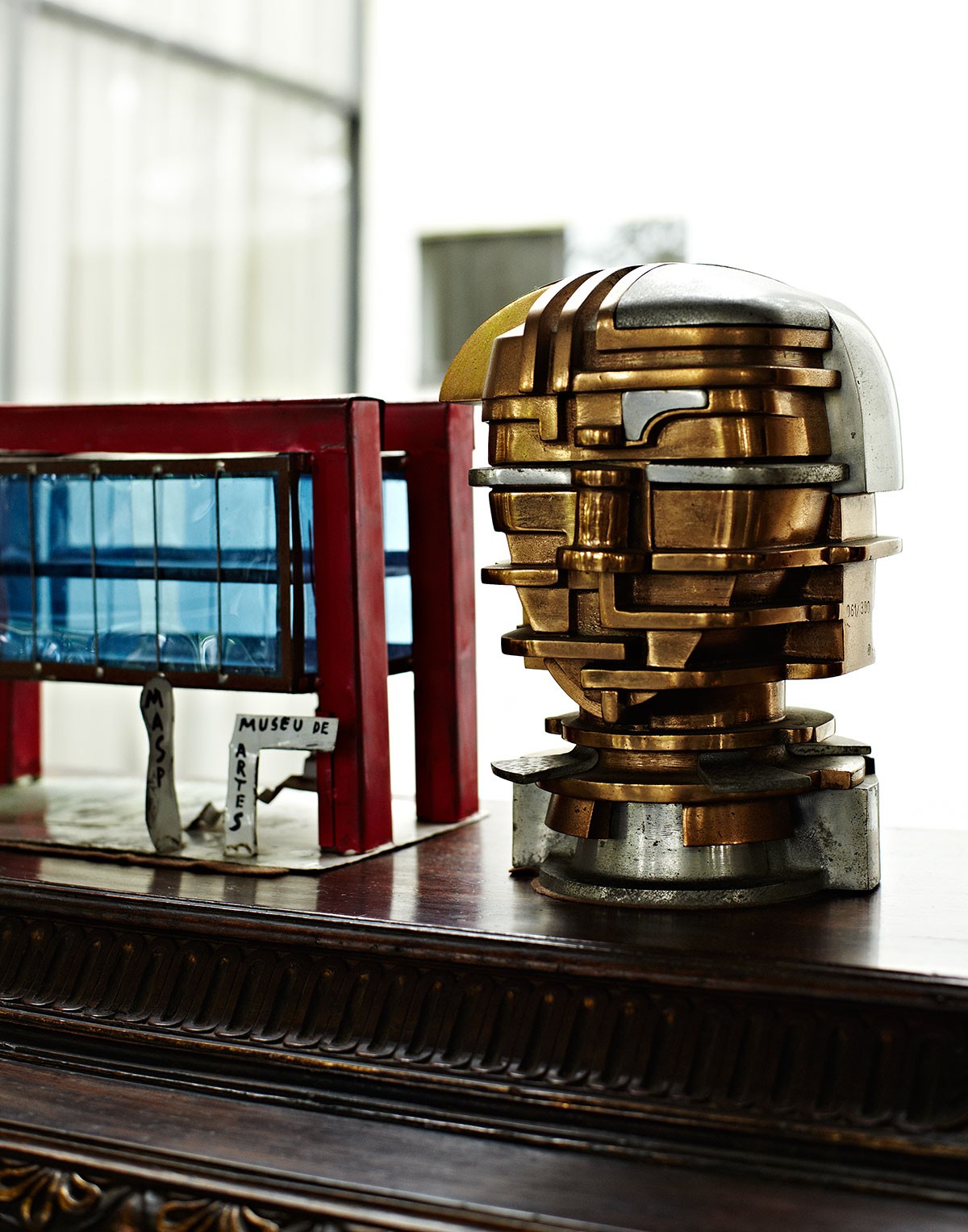

With its harmonies of light and geometry, density and apparent weightlessness, Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro (Glass House) in Morumbi, São Paulo, is one of the most beautiful of all architect’s homes. It is also one of the most important works of 20th-century Latin American architecture, forging ideas and motifs that Bo Bardi would extend and rework in her later projects such as MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo, 1957–68) and the SESC Fábrica da Pompéia (1977). The Casa de Vidro was completed in 1951, the year of Bo Bardi’s naturalization as a Brazilian, five years after her relocation from a devastated Italy. Following the war, she wrote that “in Europe man’s house is now rubble.” The Casa de Vidro, instead, defiantly looks out onto its forest surroundings with a sense of optimism, rebirth, and renewal, appearing to be both grounded within and floating above its environment. Since the deaths of Bo Bardi and her husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, a respected art critic and art historian, the couple’s former home has housed the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi. After extensive renovation work, the building reopened to the public in 2013, making the Bardis’ world available to a new audience. The Insides Are on the Outsides | O interior está no exterior, whose title is borrowed from a work by Douglas Gordon, was the final phase of a three-part exhibition that began in September 2012 and ran until May 2013. Conceived as a homage to the house’s creator, as well as an assertion of the ongoing relevance of the Casa de Vidro for today’s architectural and visual practice, it included individual works by architects and artists within the house, garden, and studio. The diversity of participants — which included architects Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and SANAA, and artists Gilbert & George, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Dan Graham, and Philippe Parreno — is testament to the enduring influence of Bo Bardi’s work across many fields.

Lina Bo Bardi's Glass House in São Paulo, photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

The works in the show, all commissioned, tell stories that reveal aspects of the house and its history that are invisible to the naked eye and create a Gesamtkunstwerk around the building, from its domestic function, scale, and form, to the trees in the garden and the institute’s archive and the late couple’s vast collection of art and artifacts. A number of exhibitors even had personal links to Bo Bardi, such as Mendes da Rocha who, like her, was a key figure of the Escola Paulista (as São Paulo Modernists became known). Prelude, the first phase of the exhibition, also showcased two drawings of the Bardis made by Alexander Calder in 1948 during his first visit to Brazil, when invited by P.M. Bardi to show his work there. Other participants never met Bo Bardi but have a clear creative connection to her work: Kazuyo Sejima of SANAA, for instance, included a prominent display of Bo Bardi’s designs at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2010. SANAA developed a new set of furniture for the library space and offices at the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, inspired by Bo Bardi’s original designs. Gilbert & George spent a day at the Casa de Vidro as living sculptures, and the photographic documentation was turned into postcards distributed to visitors. Starting from research into the Bardis’ record collection, the artist Cinthia Marcelle put together an orchestra to perform a polyphonic soundtrack for the house.

Lina Bo Bardi's Glass House in São Paulo, photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

When experiencing museums, there is often a neutral suspension of the everyday time of the world outside. The time of the home, on the other hand, is highly individual and nontransferable. As a way of exploring the idea of the exhibition as something that not only occupies space but also time, I have curated a number of shows in domestic spaces and house museums, including Huerta de San Vicente, home of Federico García Lorca in Granada (2007–08), the Casa Luis Barragán in Mexico City (2002–03), Sir John Soane’s Museum in London (1999–2000), and the Nietzsche Haus in Sils-Maria, Switzerland (1992). In these projects, as an antidote to the art world’s relentless drive to “go large,” I have tried to recover something of the intimacy of my very first exhibition, The Kitchen Show, curated in my kitchen in 1991. As the home of an unconventional couple, the Casa de Vidro has a particularly domestic feel, even if the relationship wasn’t always without tension. Cildo Meireles evoked this with his multisensory contribution to the show: while ascending the staircase to the living room, the visitor is greeted by the smell of coffee and a male voice booming, “Lina, va fare un caffè!” (“Lina, go make some coffee!”), evoking Bardi’s habit of sending his wife to the kitchen whenever a political argument was about to erupt.

Taken from PIN–UP 14, Spring Summer 2013.

Interior photography by Adrian Gaut.

Portrait by Juan Esteves.