ONE NIGHT IN... The New TWA Hotel at JFK Airport

Did Michael Kimmelman stay in the room next door to me at the TWA Hotel?

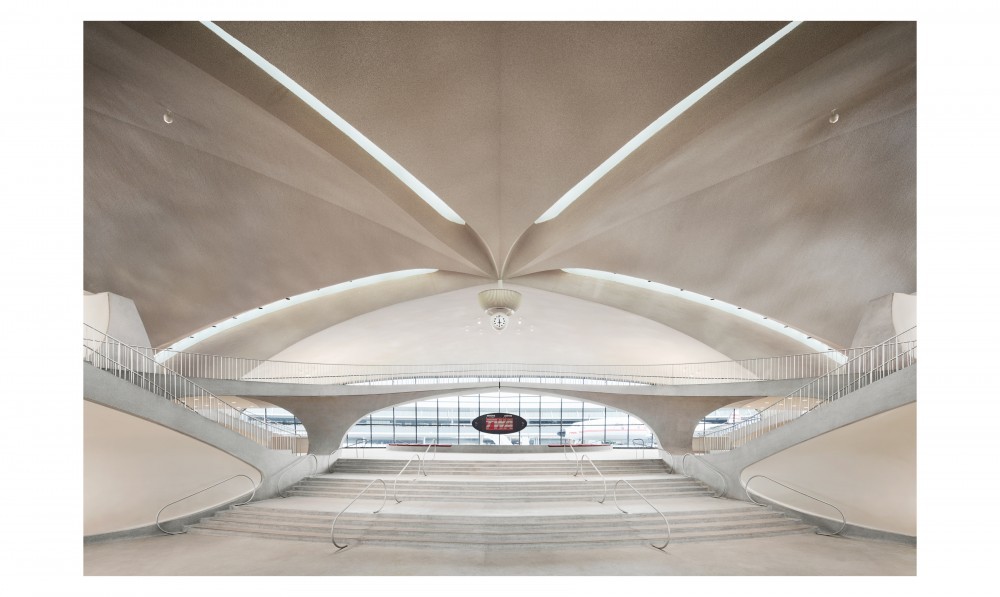

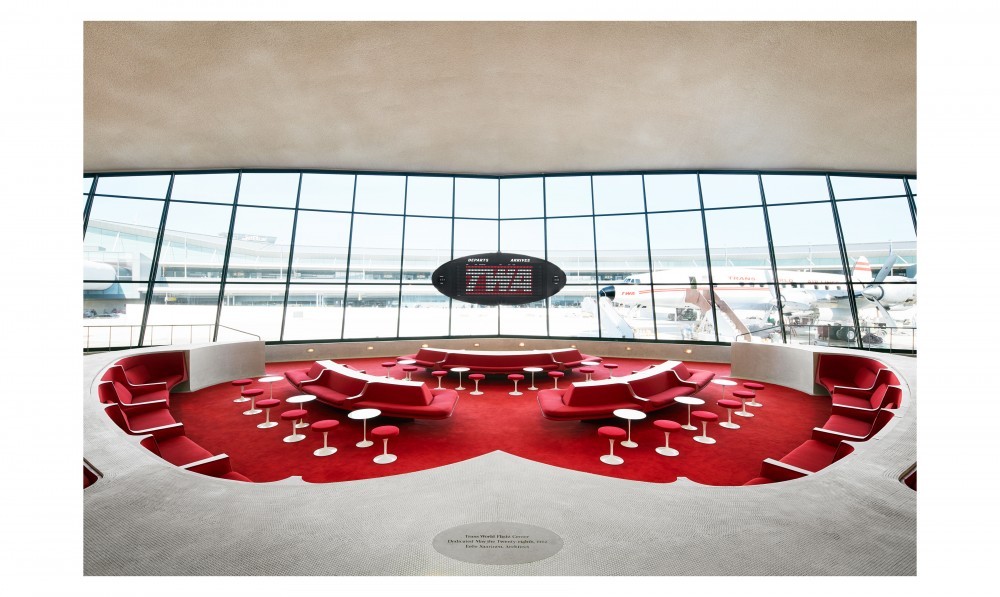

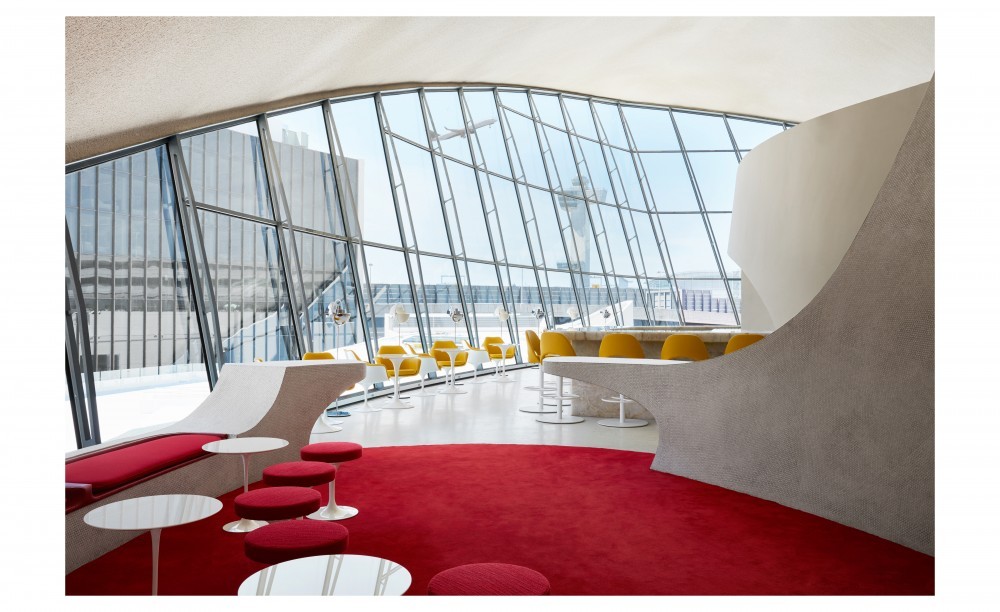

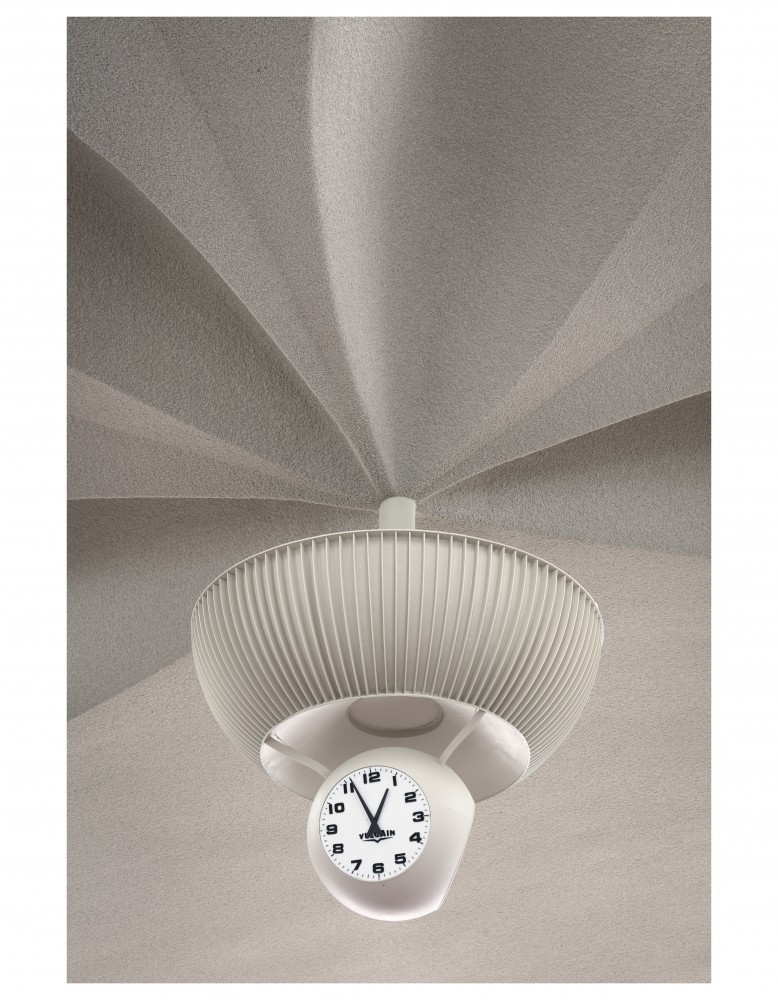

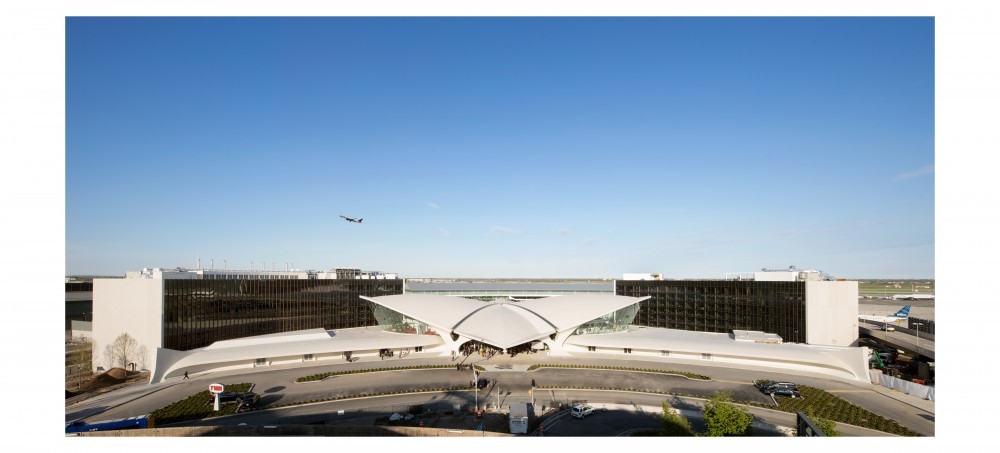

In the earnest, mannerly tones which have been his hallmark since assuming the position eight years ago, the architecture critic of the New York Times penned a mixed review earlier this month describing a stay at the just-opened, much-anticipated hospitality complex at his hometown’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. He had a lot to take in: sandwiched between two large outbuildings containing the guest rooms (the work of architects Lubrano Ciavarra, with interiors by Stonehill Taylor), the hotel lobby occupies what was once the Trans World Airlines Flight Center, Eero Saarinen’s 1962 jet-age masterpiece, arguably the finest building of his career and now lovingly restored by the firm of Beyer Blinder Belle. With a below-grade event center by INC Architecture and Design, as well as restaurants, shops, a full-service gym, and even a Phaidon- and Herman Miller-branded reading room, the hotel is — quite possibly — the first thing of any cultural significance to happen at an American airport since Dustin Hoffman descended an escalator in the opening scene of The Graduate. I went for a 24-hour stay, and by the end of it I can say I was positively dazed by the experience, though that could be as much a credit to the hoteliers as to the companion I took along.

-

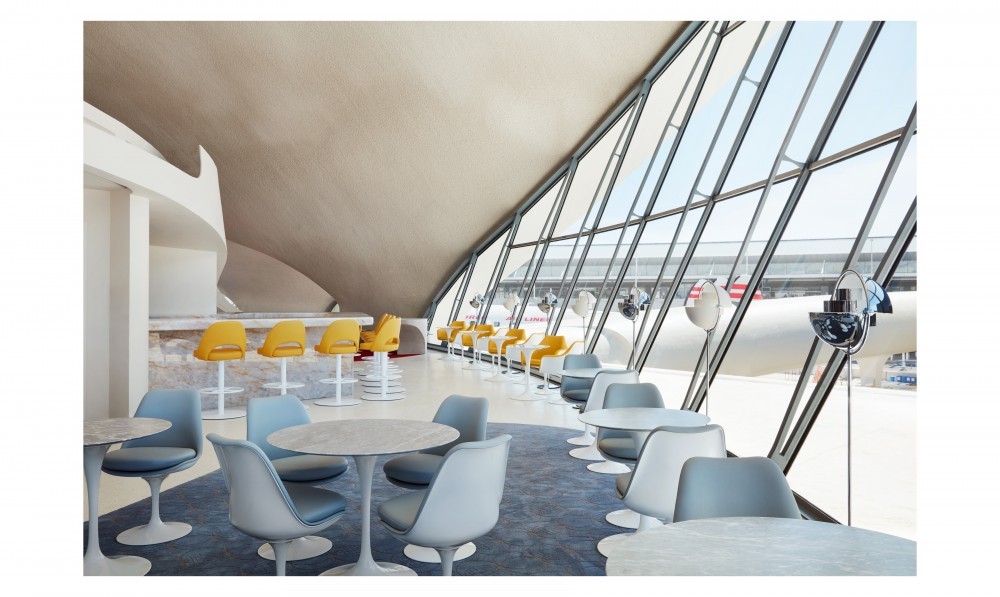

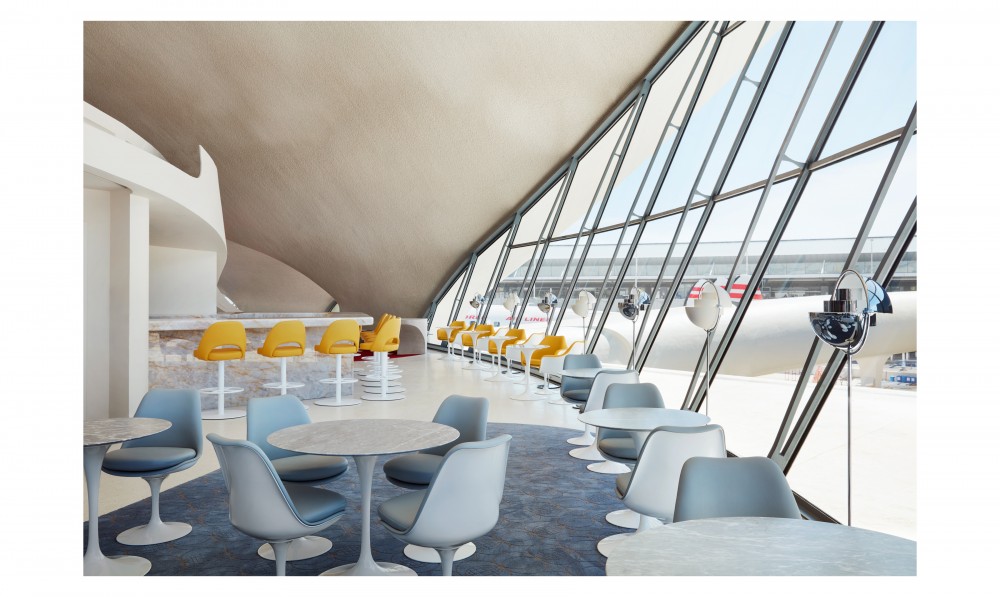

The Paris Café by Jean-Georges at the TWA Hotel offering a view of the tarmac. TWA Hotel/David Mitchell.

-

Flight Tube No. 2 at the TWA Hotel. © Christopher Payne/Esto.

-

View of the lobby at the TWA Hotel. TWA Hotel/David Mitchell.

Then why didn’t Michael Kimmelman like it?

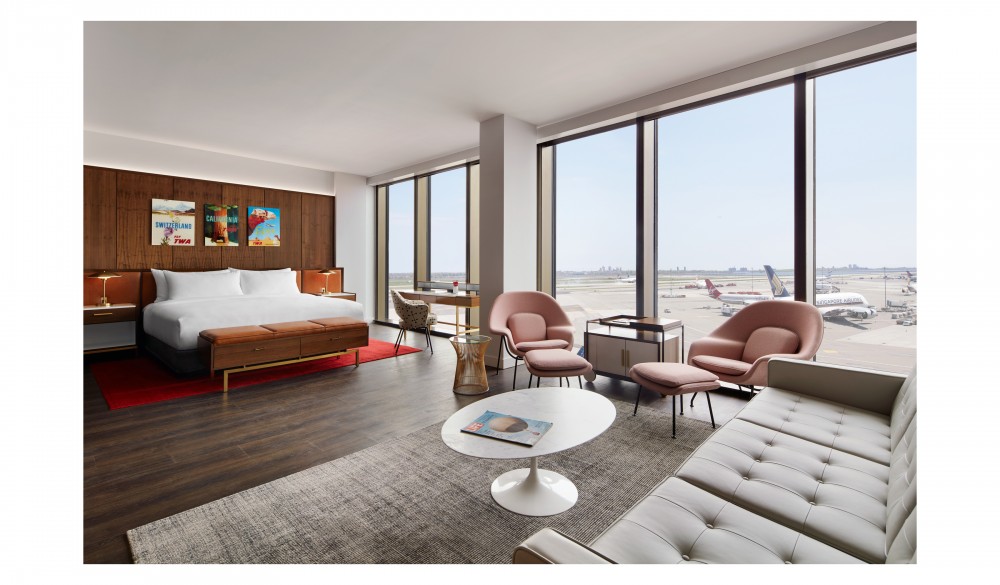

He didn’t not like it. The project poses a particular problem for a critic of Kimmelman’s stripe: He is a stalwart preservationist, credited with saving an endangered Frank Lloyd Wright house in Arizona; by his lights, that’s a mark in TWA’s favor. He has been an unfailing advocate for architecture as a public service, and for buildings as civic amenities; that gets the project a qualified thumbs-up, it being something like a piece of infrastructure (it does connect to the actual airport, via Terminal 5) but now estranged from its former utility, rendered into something closer to a private space for private fun. Finally, it is exceedingly high on camp, luxury, and commerce, all things that make Kimmelman distinctly oodgy. No expense has been spared to make even the newer spaces feel like blasts from the midcentury past, as well as to monetize that nostalgia via tote bags, posters, pencils, and almost anything that could be emblazoned with the familiar red initials. The hotel also tends, at least for the moment, to put showmanship ahead of function, and the Times critic was especially nonplussed by the inoperable window shades and occasional power outages. He might have mentioned that the shower pressure was not nearly enough for two people to enjoy simultaneously, and that the room phones (Bell 500s, natch) would not connect to the front desk, even when the occasion demanded the immediate delivery of Bing cherries and Cool Whip. Kimmelman’s final assessment was that the remade Saarninen was “exhilarating,” but that the hotel had yet to find “its groove.” He stayed, he noted in passing, with his wife.

So were we there at the same time or not?

Maybe. I knew he would be there that week, having been informed — to use a Times-ian formula — by a high-ranking figure with access to sensitive information. I thought I saw him once, going into the elevator at the end of my floor. I can’t be sure. I checked for him at dinner in the Jean-Georges-operated restaurant, and out by The Connie, a retired aircraft converted into a cocktail bar and sitting on a fake tarmac to the rear of the Flight Center. Looking out over the runways, watching real planes take off and land (a most therapeutic exercise for a hopeless aviophobe), I waded into the rooftop pool; my companion, in a period-inappropriate but otherwise unimpeachable swimsuit, asked me why I kept looking around the bar deck. I told her I was checking to see if the architecture critic from the New York Times was there. She grimaced and sipped off her mojito.

-

The TWA Hotel’s 1958 Lockheed Constellation “Connie” airplane has been transformed into a cocktail lounge. TWA Hotel/David Mitchell.

-

The TWA Hotel’s rooftop infinity pool and observation deck overlooks JFK runways. TWA Hotel/David Mitchell.

-

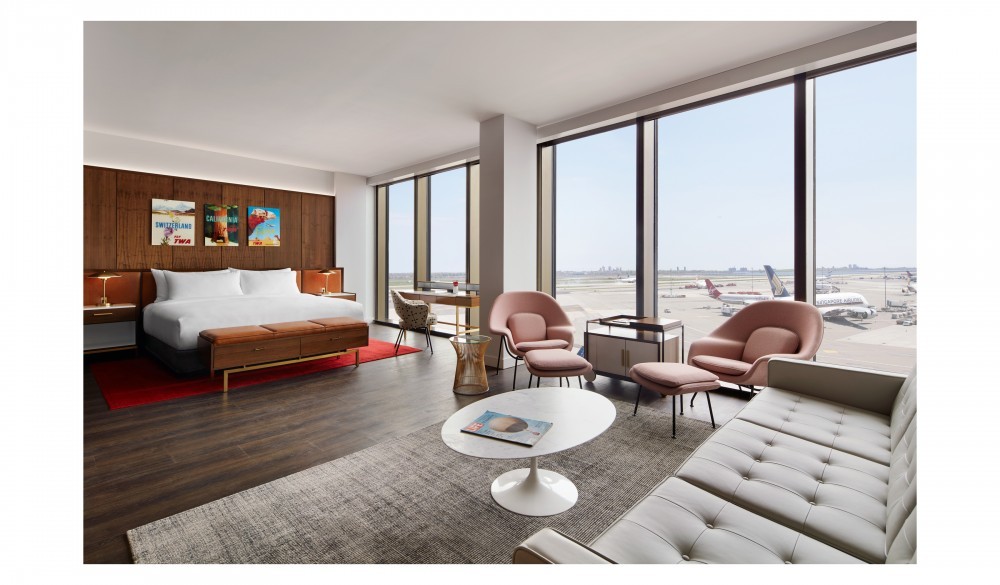

Guest room at the TWA Hotel. TWA Hotel/David Mitchell.

Okay, but what difference does it make?

As it transpired, Kimmelman revealed in his article that the pool had yet to open when he was there, suggesting I might have missed him by as little as a day. This is as well: the TWA Hotel is, in the main, not a place where one wishes to be either seen or, say, heard through a wall by anyone within one’s general professional ambit — least of all by anyone from the New York Times. The vibe at the new hotel is one of superlatively louche escape, the romance of the 1960s structure combining with the otherworldly oddness of simply partying at the airport to suffuse the whole environment with a giddy eros: nitrous oxide for the architectural soul. Custom and convention always go by the boards in airports, places where people routinely sleep on floors and drink at 11AM; TWA takes the same atmosphere, refines it to its quintessence, and then sets a hefty price tag on the whole affair. And it is this that puts not just Kimmelman, but all of us, in a bind: Saarinen’s building was always (to recall Christopher Rawlin’s book on Horace Gifford) an architecture of seduction, daring you to keep your critical cool and not get swept up in its lushness. In its revived form, it does the same thing all over again, only more so. Try as I might, I couldn’t resist it, and as I write this now — wearing, I would add, my new red TWA t-shirt — I still can’t.

Text by Ian Volner.

Images by David Mitchell unless otherwise noted.