IN PRAISE OF SHADOWS: Paola Jose wants us to Reconnect with Darkness

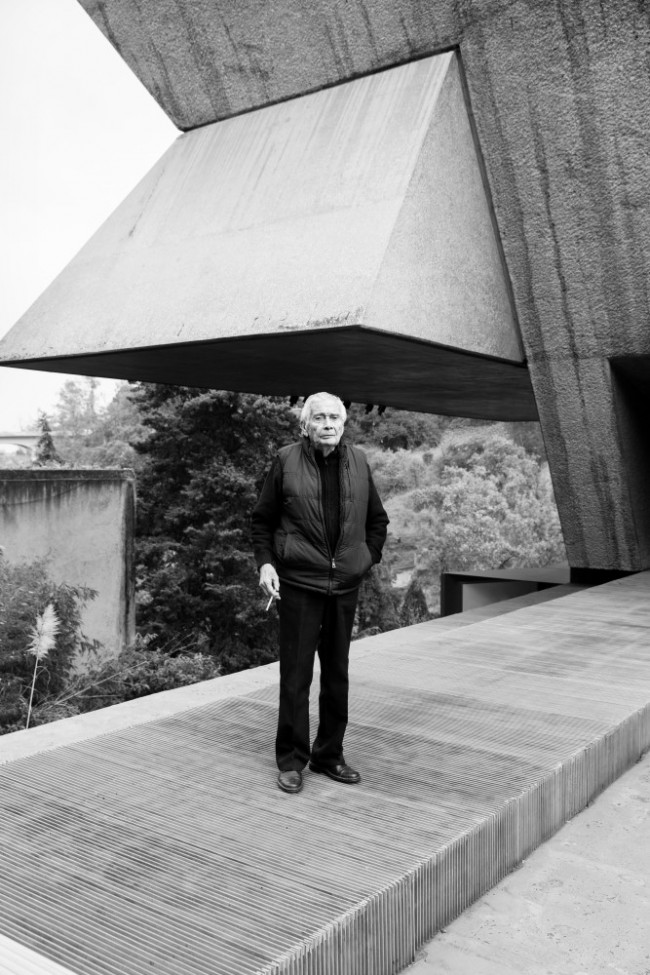

Portrait of Paola Jose by María Jaber.

The stars rarely shine in Mexico City, a metropolis of over 9 million inhabitants flooded with ambient light. Halogen streetlamps and neon signs stain the thickly polluted air a hazy orange. When the designer Paola Jose was growing up in the neighborhood of Colonia Navarte, she longed to know darkness: not just the inky black of the night sky but shadows that could throw the city’s light into sharp relief. In 2016, she founded her firm SOMBRA — Spanish for “shadow” — around the principles of low, sustainable lighting. Since then, she’s produced some of Mexico’s most exciting work in the field, like the hanging lamps she designed for Monte Uzulu, a boutique hotel that opened in 2019 on the rugged Oaxacan coast. Jose drew on indigenous craft traditions, enlisting local artisans to work from a straw called popotillo, to cast dappled light on the hotel walls without obscuring nocturnal views of the Milky Way. These shadows were meant to mimic the waves of the ocean. “Darkness is like silence,” she said. “It’s become a luxury. We don’t need that much light; we need to reconnect with darkness.”

Paola Jose’s Yacamán series, photographed by Andrea Cinta for Base Agency.

Jose’s bible is the 1933 classic In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanizaki — a manifesto of wabi sabi design that celebrates natural imperfection. “We delight in the mere sight of the delicate glow of fading rays clinging to the surface of a dusky wall, there to live out what little life remains to them,” Tanizaki wrote of his fellow Japanese, scorning the electric lights that had then become popular in his hometown Kyoto. “We never tire of the sight, for to us this pale glow and these dim shadows far surpass any ornament.” For Salon Rosetta, Jose’s most significant project in Mexico City that opened earlier this year, she installed small, dimmable Murano glass luminaires on the tables in the intimate cocktail bar atop the popular, eponymous Roma restaurant. Light subtly glints off the jade lacquerware and green velvet couches.

Paola Jose’s Yacamán series, photographed by Andrea Cinta for Base Agency.

Jose studied mechanical engineering at the University of Texas, Austin, where she was especially drawn to the physics of optics. Eager to apply her skills in a more creative way, she pursued a Masters in Architectural Lighting Design at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. She was shocked when her first assignment was to bring in a picture of her favorite light. She presented a photograph of a sunset on the beach in Oaxaca — not far from where she would later collaborate on Monte Uzulu. Upon graduating, she began collaborating with light artist Paolo Montiel-Coppa, and in 2014, she managed the technical installation of James Turrell’s Encounter skyspace in Culiacan, Mexico. Set within an earthen mound in a dense jungle botanical garden, Encounter — like all of Turrell’s skyspaces — is activated at sunrise and sunset, and finely tuned for the specific natural light at its location. Like the work that Jose would soon produce as SOMBRA, it’s art designed to be responsive to the sky.

Paola Jose’s Yacamán series, photographed by Andrea Cinta for Base Agency.

Jose’s keen eye for shadows has made her a natural collaborator over the years. In 2019, she produced the stage lighting for a cycle of six dances choreographed by dancer Diego Vega at Loot, a gallery in Mexico City. The project doubled as new architectural lighting for the gallery by employing the Ketra system, which Jose adjusted in real -time using an app on her phone. They reprised this collaboration in November of last year, this time at the Casa Estudio Luis Barragán. Jose took a very different approach to her June 2021 collaboration with Ananas Ananas, a Mexico City-based collective, at a 1950s Buddhist temple in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. She housed yellow and orange lights in Japanese lanterns and sunk them in piles of sand and dried palm leaves to light an experiential meal that attendees consumed with their hands off bricks and adobe tejas. The raw, low lighting, she told me, was meant to enhance the sensory experience: “When you see less, your taste becomes more activated.”

Paola Jose’s Yacamán series, photographed by Andrea Cinta for Base Agency.

When Jose and I met at Casa Naila last year, a beautifully austere villa designed by Alfonso Quiñones on a remote stretch of the Oaxacan coast, the house was playing host to the inaugural edition of the Mexico Design Fair. SOMBRA was one of over a dozen exhibiting artists, and she had produced a new line of lamps for the occasion. She named it Yacamán series, for her late father, who passed away recently. Her grandfather, a doctor who emigrated from Syria, passed on his medical practice to her father along with his collection of antique surgical lamps. As a child, Jose loved visiting the office and playing with their swiveling robotic arms. On one of her Yacamán lamps, a shallow silver dish reflects the light from a bulb. Attached by a leather strap to a cone of Mexican volcanic rock called racinto, it looks like an antique medical headlamp — or a minion from the cartoon film Despicable Me. An elegant chandelier, meanwhile, looked slightly out of place in Naila’s spare interiors, with its gentle cascade of golden dishes catching the last rays of the sunset through slatted walls.

Paola Jose’s Yacamán series, photographed by Andrea Cinta for Base Agency.

At nightfall, while we spoke, an enormous sea turtle wandered up the dark beach and began to dig a hole in which to lay her eggs. Fairgoers were warned not to shine their camera lights in her direction. As we watched nature at work, Jose noted, “Before electric light, it wasn’t possible to receive medical treatment at night or in a dark room. I think it’s beautiful to consider the ways that light can heal.”

Text by Evan Moffitt

Evan Moffitt is a writer, editor, and critic based in New York City.