CRITICAL CONDITION: Interview With CCA Director Mirko Zardini

The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) is a peculiar place. The Montreal-based institution was founded 40 years ago by the now nonagenarian powerhouse Phyllis Lambert. Lambert collaborated with architect Peter Rose on the design of the late-80s postmodernist masterpiece that holds the CCA’s archive, exhibition spaces and offices, and envelopes a 19th-century mansion which Lambert saved from demolition in the 1970s. Despite the implications of its title, the CCA exhibits and collects without national cultural obligations and so operates with a fierce independence. Its collection is broad and eclectic, from Siza to snow globes, Le Corbusier to Lego, and grows with an intellectual rigor matched by its research, publication, and exhibition outputs.

For the last 15 years, the CCA has been directed by Mirko Zardini, an Italian curator and architect with an appetite for the disruptive. His leadership has seen the center consolidate its position at the edge of Western architectural discourse’s intellectual (and geographical) mainstream with exhibitions and publications that are critical above all else. Curatorial projects dissecting healthcare, Canada’s fractured relationship with its natural landscapes and, more recently, happiness, have under Zardini’s watch been unleashed on the Montreal public and beyond. Where in the U.S., U.K., and elsewhere the need to reach broad publics for funding purposes can result in lukewarm or patronizing work at ostensibly similar institutions, the CCA often appears unafraid of challenging its audiences. This approach is not without its criticism and CCA projects have been seen as aloof or overly intellectual. That said, it’s an approach for which Zardini provides eloquent defense. PIN–UP visited the CCA and spoke with Zardini on the occasion of The Museum is Not Enough, a new project questioning the role of architectural institutions in the context of the CCA’s 40th anniversary.

How does The Museum Is Not Enough relate to the CCA’s 40th anniversary?

The Museum Is Not Enough comes out from a frustration that I have with the role that institutions are playing in the contemporary situation. I feel that institutions are not really taking clear cultural and political positions and they are not really contributing to an advancement of the debate or critical thinking that is needed today. I’m not saying all institutions. But most of them. They are playing very safe, reproducing a very traditional idea of an institution.

They are protecting themselves under the loyalty to a mission that they have. But if you look at all the missions of the institutions they are always good. Did you ever find a mission that is wrong? No. So the problem is not the mission, the problem is how you interpret that. And I have to say that the mission of the CCA in itself is “To make architecture a public concern.” If you critically analyze how this mission has been interpreted at the beginning of the CCA and how the CCA is interpreting that today, it’s very different. At the beginning, “To make architecture public concern” was part of a very specific idea of architecture as an intellectual autonomous practice. History played an important role. It was more about establishing recognition for architecture as a discipline and as an intellectual practice, more than really contributing to a critical debate. My objective was to go back to some of the genetic components of the institution, for example the intention that was expressed at the beginning, to create an imaginative and polemic institution.

Giovanna Borasi, Chief Curator. Photography by Stefano Graziani for The Museum Is Not Enough. © CCA

What do you think is at the root of the failure of these other institutions to think more critically? Is it a question of getting people through the door? Is it a lack of imagination? Or to put it another way, what do you think allows you and the CCA to approach the idea of the institution differently?

The first important thing is for an institution to be independent. And if you want to have an intellectual or cultural or political position, you have to be ready to pay for that. We have lost some grants. Our objective was never to have a large public. We’d like to have a large public but that is not an objective. Our objective is to build a discourse and everything else is a tool to build this discourse. So an exhibition is never an objective, it’s always a tool. A book is never an objective; it’s always a tool. The website is not an objective, the objective is not to increase the number of visitors. The objective is how can we build a conversation that would be interesting and then how can we make this a conversation shared with a larger group of people. But clearly one works in a position of minority; you don’t expect that what you say will be good for everyone. You accept that. Most institutions want to be accepted by everyone. They want to have a large number of visitors, they want to be successful in terms of quantity. If you look at how most institutions are dealing with social media, it’s simply a way to get bigger numbers. To engage the public and to engage a larger public, on the basis of what? Of values and considerations that are typical of the 19th-century in which the institution has an educational role. The institution knows and it will tell you the truth. This is simply unacceptable. So that’s why we abolished the education department and we have the conversation department.

In The Museum is Not Enough, you write, “I’m very attracted to this idea of edges, perhaps because when I’m there I can be freer from the pressure of norms and can have a better vantage point to make sense of this rapid change.” Could you speak a bit more about this idea of an edge condition? In terms of being on the edge of the discourse, but also what does that mean geographically? Being here in Montreal does that play a role in this edge condition somehow?

Yeah I have to say the fact that the CCA is in Montreal offered me the opportunity to rethink the institution. Immediately I realized that one couldn’t build the public conversation with such a large number of people as you could do in New York. Before I accepted the position of director, I asked a lot of people, and they were simply telling me, “Very nice institution, but it’s in the wrong place.” In reality, we have the opportunity to be out of the pressure and the expectations. The idea that I tried to develop was to have an institution that was in Montreal but was also in other places — the idea of an institution as a network. The digital component was part of this, but also CCA c/o and CCA elsewhere (events and programs taking place outside of Montreal), these are ways to have an institution that is in different places at the same time. So the idea to be at the edges is interpreted also in cultural terms. To be always at the edge offers an interesting position because you are never outside and you are never inside. So the idea of the edge is offering an incredible position because if you are completely outside you become irrelevant and if you become completely inside you become irrelevant.

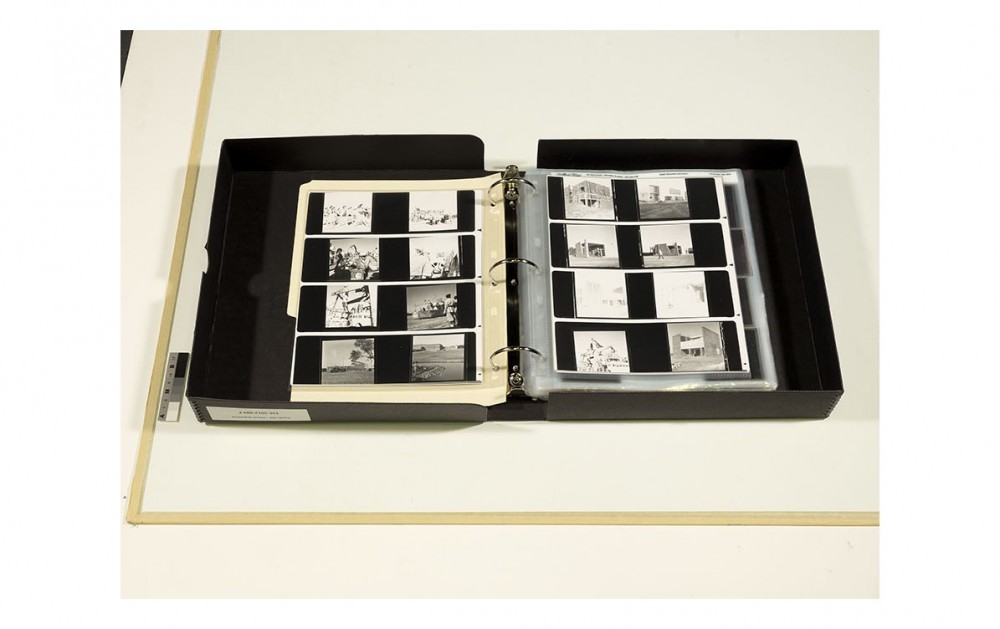

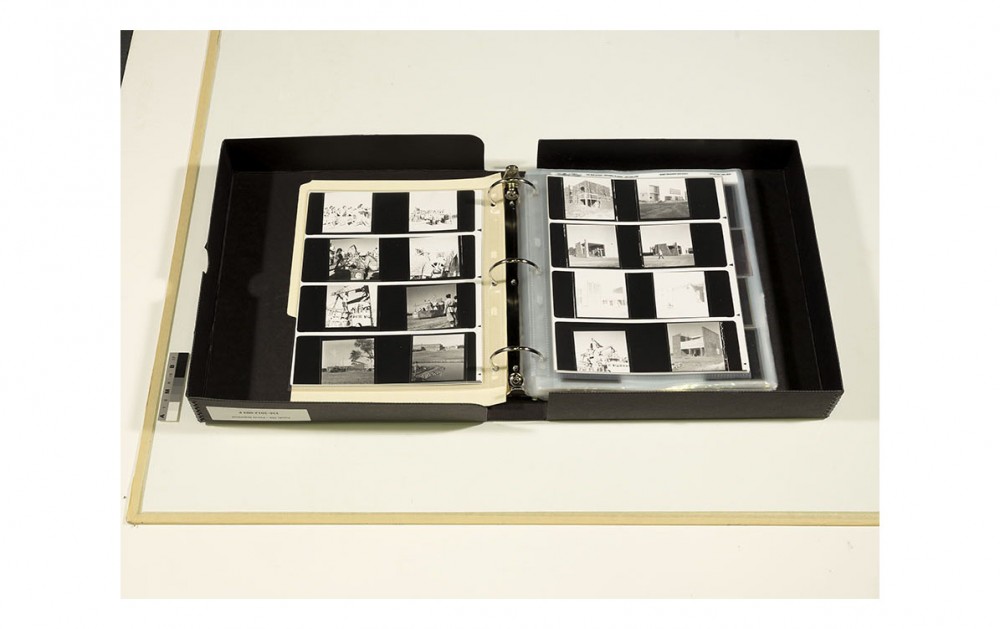

Contact sheets. Pierre Jeanneret fonds, Photographs, Collection Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret. Photography by Stefano Graziani for The Museum Is Not Enough. © CCA

Going back to thinking about Montreal, we are in the center of the city here. What do you think it means for the city itself that the CCA has been around now for 40 years?

It means a lot of different things for different people because for a lot of people the institution is still considered a traditional institution. We are happy to welcome these people. But in reality our public in Montreal is mainly a younger public, students and professionals, but also very multidisciplinary.

Is that a recent development or is that something that’s been consistent throughout its history?

It’s happened in the last ten to 15 years.

So that roughly equates to the time that you’ve been director.

Yes, I pushed for that. When you go to speak with professionals they say, “Who is your public? Let’s analyze your public.” And then, “This is what you have to do to make your public happy or interested.” My point is that the public does not exist. You have to build your public. My intention was to build the public that I like. And to establish a conversation with a public or a group of people that I was interested in. And I found in Montreal that component of a younger public coming from sociology, from political studies, and not only from architecture, was more interesting than only the architectural public.

Albert Ferré, Associate Director, Publications and Louise Désy, Curator, Photographs. Photography by Stefano Graziani for The Museum Is Not Enough. © CCA

How do you see these cultural institutions changing in the years to come?

I am not very optimistic because I think most of the institutions would rather take the short way to pretend to solve problems and offer solutions than to develop a critical voice. For example, when there was the financial crisis, a lot of institutions were proposing themselves or art as a way to heal the stress, the conflict, the situation, these kind of things. So that is what I call a “consolatory role” in this kind of situation. It’s not what I would like. I would like the institution to take a very clear critical, even political position. But I don’t know if they are ready to articulate a conversation that is not acceptable for everyone, that might be dissonant with some part of their public.

And how about you? You’ve been here 15 years, are you sticking around.

(Laughs.) This accident is making me think it was a sign of destiny. Look, I really want to consolidate this transformation of the institution before giving up. The tendency of an institution is to freeze. They are very conservative bodies. As soon as they find a condition, they try to maintain that. So the problem is how you can create a culture that will maintain an institution in a transformative line? How you can engineer permanent elements of friction? How can you raise questions you didn’t already think of? Ask you things you aren’t ready to answer, putting you in a crisis? At the same time you need a core of the institution stable enough in order not to dissolve. So it’s a balance between the core and the crisis. You balance this in order to have a proper transformation.

So if I understand you correctly, you’ll be happy to move on when you know that the institution can keep evolving without you? That it can keep manufacturing its own crises without you?

Yes, because for the moment I have been the one that created a lot of the crises.

Text by George Kafka.

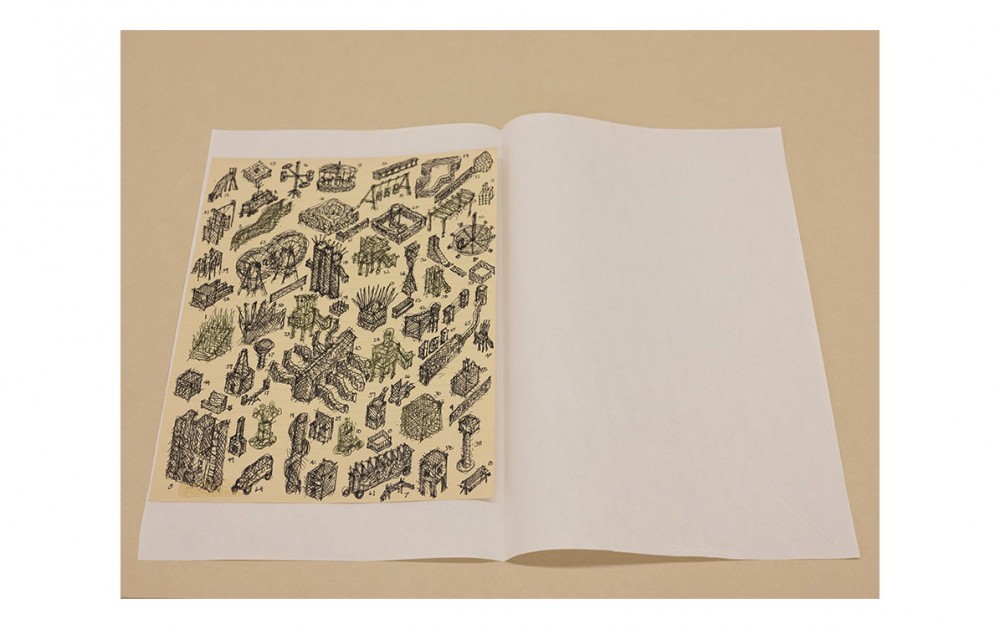

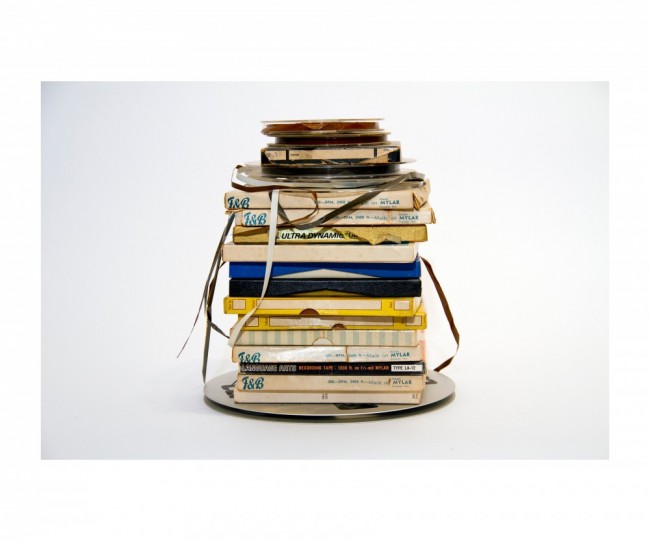

All images are photographs of CCA workspaces and collection material by Stefano Graziani for The Museum Is Not Enough.