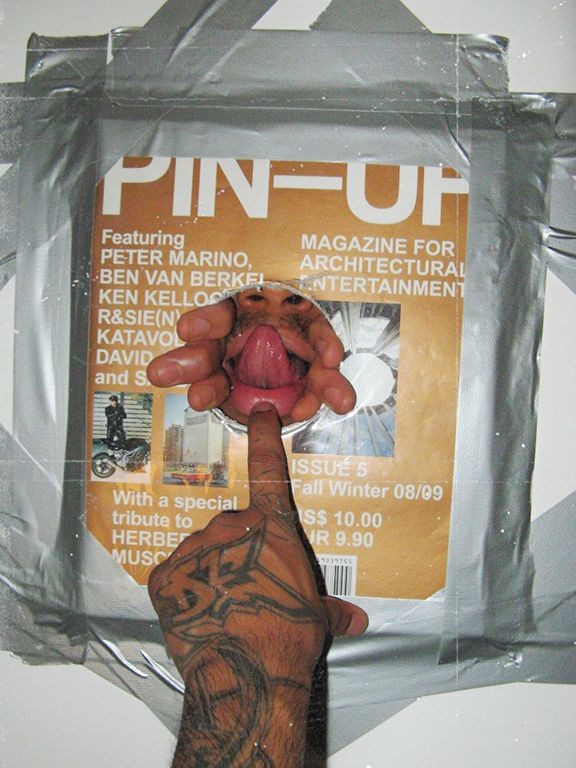

LAST CALL: Is Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Arc a Triumph?

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021) by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, photographed in Paris by Tanya and Zhenya Posternak.

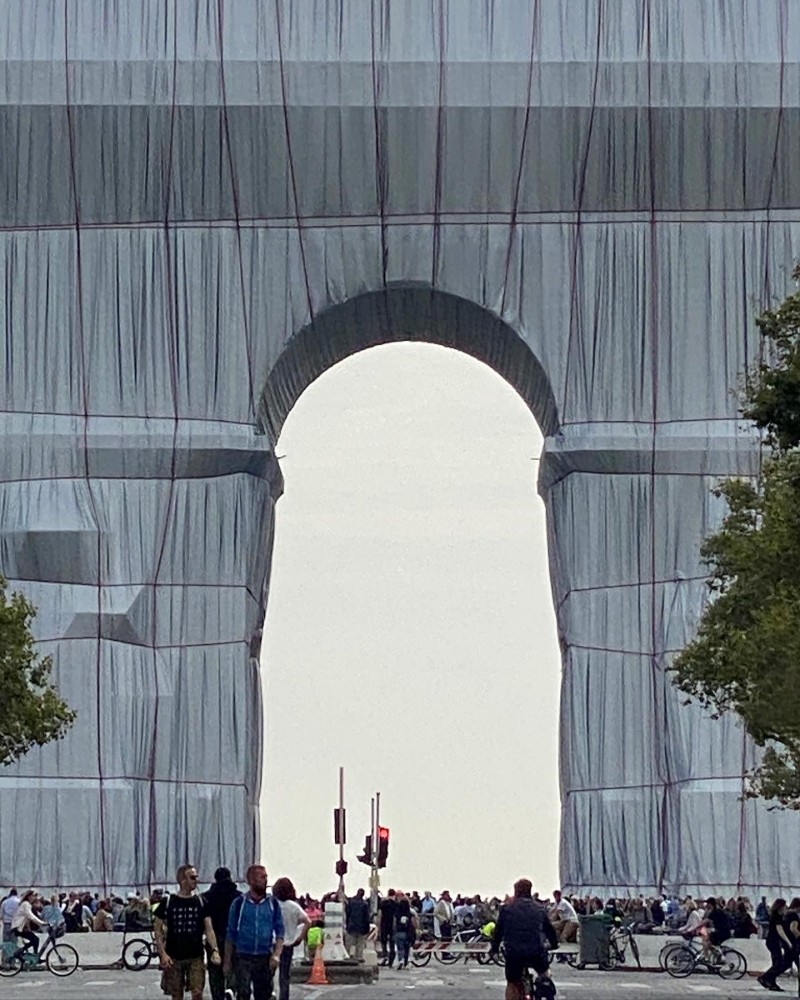

“TAKE MORE PHOTOS” urges a sticker on a street sign at Paris’s Place Charles de Gaulle, home to the bombastic Arc de Triomphe, the world’s largest triumphal arch. Chances are the Napoleonic monument will never have been photographed so much as right now, thanks to Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935–2009), the artist duo collectively known as Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Their L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped was already all over Instagram and Twitter a week before its official inauguration on September 18. Back in 1962, the Arc was among the first monuments Jeanne-Claude and Christo proposed to package, and the realization of the project six decades later can be seen as a posthumous triumph for the Franco-Bulgarian pair. But does this victory from beyond the grave have a slightly Pyrrhic taste?

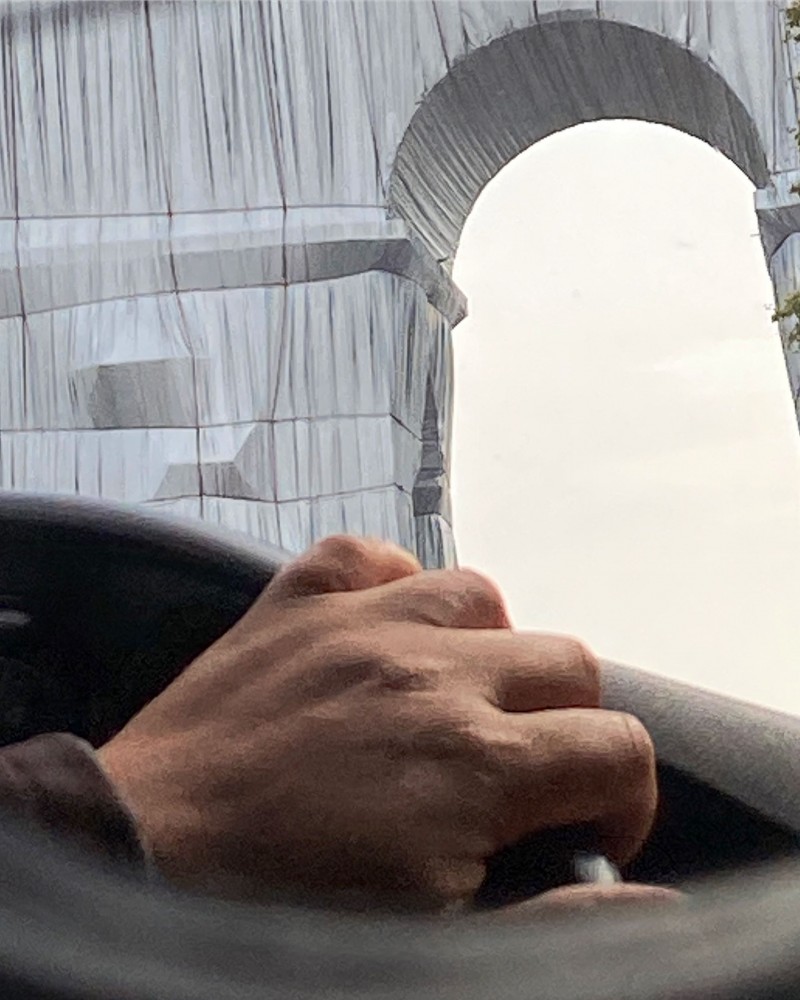

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021) by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, photographed in Paris by Tanya and Zhenya Posternak.

Fifteen years before Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s birth, in 1920, the American artist Man Ray made The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse, a black-and-white photograph of a mysterious object wrapped up in cloth and string — a Singer sewing machine, as it turned out. Man Ray was unlikely interested in the fortune made by Singer’s invention or the way it had revolutionized working women’s lives, the choice of object referring instead to the celebrated line in Ducasse’s novel Les chants de Maldoror: “He is as fair … as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

Four decades later, a penniless, stateless defector from the communist bloc began to package the everyday objects of Western consumer society. However much Jeanne-Claude claimed their art was a purely aesthetic endeavor, at its best the couple’s work always had a political edge. Christo himself admitted as much when he explained that he’d pulled the plug on Over the River, the project planned at the U.S.-government-owned Arkansas River. His reason: he did not wish to benefit the new “landlord,” whose name he refused to pronounce (it was then-president Donald Trump). On the occasion of the duo’s best-known and most audacious project, the 1995 wrapping of Berlin’s Reichstag, Christo explained, “The Reichstag would have meant nothing to me had I not been born in a communist country.” Art is a scream of freedom was the duo’s rallying cry.

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021) by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, photographed in Paris by Tanya and Zhenya Posternak.

Freedom for the Christos also meant financial independence. According to their official website, L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped receives no public funds and is “entirely funded by the Estate of Christo V. Javacheff, through the sale of Christo’s preparatory studies, drawings, and collages of the project as well as scale models, works from the 1950s and 1960s, and original lithographs on other subjects.” When they wrapped the Reichstag, they didn’t just hire the building itself but also the perimeter around it, so that no unauthorized commercial exploitation of the event could take place; when they realized The Gates in New York’s Central Park, in 2005, they paid the city $3 million in rent so that no movies or TV shows could be filmed on site during that time. But what no one ever talks about are the implications of this independence: the Christos were running a multi-million-dollar business whose rights they tightly controlled.

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped has officially cost €14 million, which is cheap in comparison to the reported $15 million spent on Over the River before the project was aborted. Does one really raise those kinds of sums through the sale of preparatory drawings? Certainly there’s a whole Christo spin-off industry that has sprung up around their projects, as evidenced by the current Christo exhibitions in (Paris)(Hyperlink: https://www.cahiersdart.com/en/gallery/), Zürich, and New York, the two new books on the Arc de Triomphe project, as well as a Sotheby’s sale. Moreover it’s a business that can carry on postmortem. Toward the end of his life, Javacheff estimated that in his half century of realizing large-scale wrappings he had successfully completed 23 works but failed to secure permission for a further 47; if Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe buildings can be erected decades after they died, there’s nothing to stop Christo plans being put into action for another century to come. The artistic freedom Javacheff found in the West was entirely rooted in the market economy, and that is perhaps the ultimate political statement the couple’s art makes.

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021) by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, photographed in Paris by Tanya and Zhenya Posternak.

“Respectable?! Of course I’m respectable, I’m old!” yells John Huston in the 1974 movie Chinatown. “Politicians, whores, and ugly buildings all get respectable if they last long enough.” Jeanne-Claude was born into the establishment — the daughter of an aristocrat who was a general in the French army — but rebelled when she left her then husband for the impoverished, position-less, working class Javacheff. He, meanwhile, claimed always to have felt an outsider in the West, even after decades in his adopted hometown of New York. Twenty years ago, it would have been unthinkable for the Arc de Triomphe to be wrapped; but now that the last French war veterans of the two world wars have died, that the country’s relationship with its military has evolved, and even the memory of the Cold War is beginning to fade, the gesture no longer appears the least bit controversial. To package the Arc, the entire spectrum of the French authorities — the government, the army, the City of Paris — had to be brought on board. Where once a Christo work was a polemical act, it has now been fully accepted as “merely” art. Is this then the Christos’ fate? To have become official, respectable, inducted into the dead canon of the academy? A cash cow for their heirs and descendants? Their eminently Instagrammable wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe an eviscerated, irrelevant — not to mention wasteful — gesture from another age?

Text by Andrew Ayers

Photography by Tanya and Zhenya Posternak