Sarasota Art Museum Takes Over A High School And Rudolph-Designed Ancillary

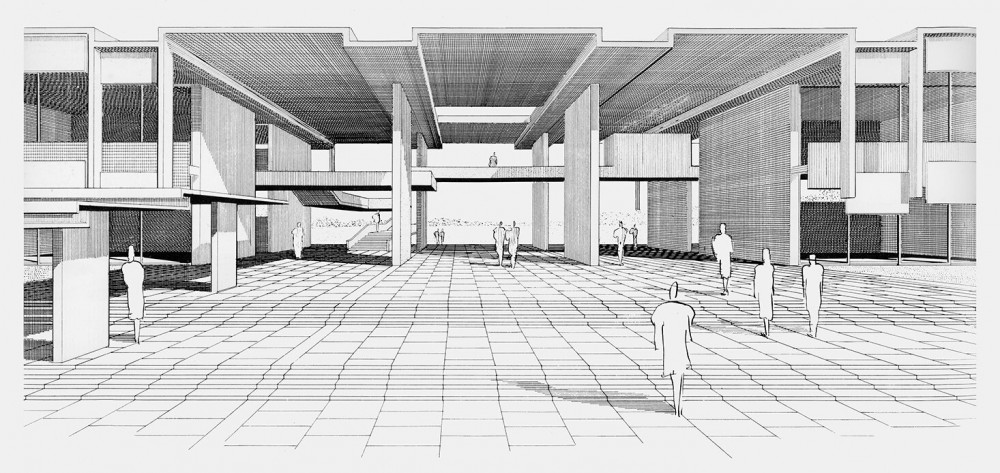

A new contemporary art museum in Sarasota, Florida marries a three-story red-brick collegiate-Gothic building with a low-slung Modernist one. Designed by Terence Riley — a principal of New York-based firm Keenen/Riley and former director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami — the Sarasota Art Museum of Ringling College gives new life to this odd pair of buildings, which were originally a high school. In 1951, a young Paul Rudolph built an addition to house trade classes behind the M. Leo Elliott-designed brick-and-terracotta structure, which dates back to 1926. The fact that the Rudolph building looked to the future while the Elliott building looked to the past wasn’t the only challenge when making the museum. Riley also had to reorganize the site, making the courtyard between the buildings the centerpiece. “Before it was a dumping yard for garbage,” he deadpans. What used to be the Elliott building’s rear is now the museum’s main entrance, to which Riley has added exposed concrete shadow boxes that mirror the façade of the Rudolph building opposite, putting the two structures in conversation and activating the courtyard space.

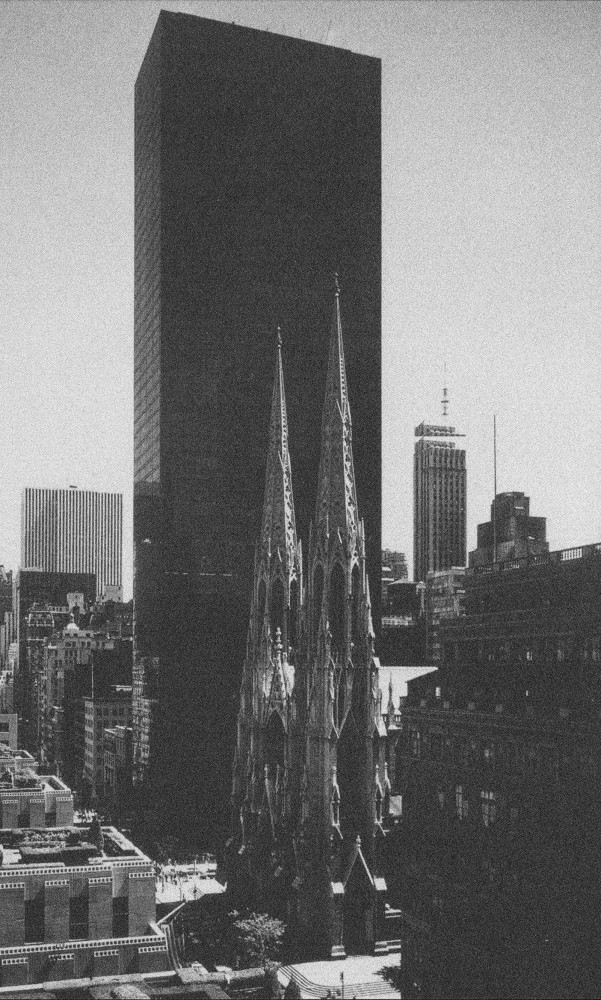

A vintage postcard showing the 1926 Sarasota High School building, now converted into the Sarasota Art Museum.

The new museum, which opened in December, spotlights Sarasota’s mid-century-Modern heritage largely influenced by Rudolph. In 1952, historian Henry Russell Hitchcock declared in The Architectural Review that “the most exciting new architecture in the world is being done in Sarasota.” Fresh out of Harvard, Rudolph had moved to Florida in 1947 to partner with Ralph Twitchell, an architect nearly 30 years his senior, who’d set up shop in Sarasota before World War II and, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, begun experimenting with reinforced concrete and glass. Twitchell and Rudolph’s work attracted other architects to the area like Gene Leedy, Tim Seibert, Jack West, Victor Lundy, William Rupp, and Carl Abbott, giving rise to what became known as the Sarasota School, which flourished into the mid 1960s. One of the surviving Modernist landmarks is the still-operational Rudolph-designed Sarasota High School (1958–60, on the same block as the Sarasota Art Museum), a study in white-concrete folded planes with an open-air breezeway connecting classrooms, and cantilevered brise-soleils.

-

The new museum’s main entrance is through

the courtyard, where the original 1926 structure meets Paul Rudolph’s 1951 addition. Photography by Ryan Gamma -

The main building of the Sarasota Art Museum was originally built in 1926 to house the Sarasota High School. Photography by Ryan Gamma

-

The new museum’s main entrance is through

the courtyard, where the original 1926 structure meets Paul Rudolph’s 1951 addition. Photography by Ryan Gamma -

Riley reorganized the site to activate the courtyard space: “Before it was a dumping yard for garbage.” Photography by Ryan Gamma

Rudolph built an identical sculptural canopy nearby at the then high school of which a 10-foot section was removed when construction on the museum began to allow trucks to enter the site. This “caused a global shit storm amongst Rudolph preservationists,” according to Sarasota Art Museum executive director Anne-Marie Russell, who was able to save the rest of the canopy from being bulldozed. “This museum was headed for a train wreck before Anne-Marie and I came on board,” recalls Riley (who, in 2015, launched Parallel, with John Keenen and Joachim Pissarro, a consultancy uniquely geared towards buildings for the display of art). “There was initially a plan in place designed by an architect who specialized in assisted living facilities. One totally ridiculous part of his design was a double-height artist’s studio where people visiting the museum could overlook the artist working, like in a zoo.”

A sketch from the late 1950s of the still-in-use Sarasota High School (1958–59) designed by Paul Rudolph.

Russell, who oversaw the entire renovation since becoming director in 2015, has big plans now that the structure is finally open to the public. Conceived as a Kunsthalle, with no permanent collection, the Sarasota Art Museum opened in December with a retrospective of Brazilian-American artist Vik Muniz as well as Color. Theory. & (b/w), a group show running until July 2020. The latter features heavyweights like Sheila Hicks and Kara Walker as well as local artist Christian Sampson, whose installation Vita In Motu conscripts Sarasota’s main attraction: the sun. Its rays filter through colored gels projecting an ever-changing light painting on the gallery wall — “a reminder,” says Russell, “that we’re on a spinning globe.”

Text by Whitney Mallett.

Photography by Ryan Gamma. Courtesy Sarasota Art Museum of Ringling College.