POM-POM-PIDOU: FRANCESCO VEZZOLI REVERTS THE LEGENDARY PARISIAN MUSEUM INTO A FUN PALACE

Programmed in 1969 by France’s then president, the Centre Georges-Pompidou turns 40 this year. The future — for futuristic was how Piano and Rogers’s exoskeleton supermarket of art appeared to its very first visitors on February 2, 1977 — is now middle-aged. A whole year’s worth of celebrations has been organized at 40 sites all over France, but the highlight of the birthday festivities arguably took place on October 19 in the building itself. For just one evening, levels five and six were given over to the enfant terrible of Italian contemporary art, Francesco Vezzoli, who had carte blanche for an extravagant performance-cum-artwork-cum-soirée.

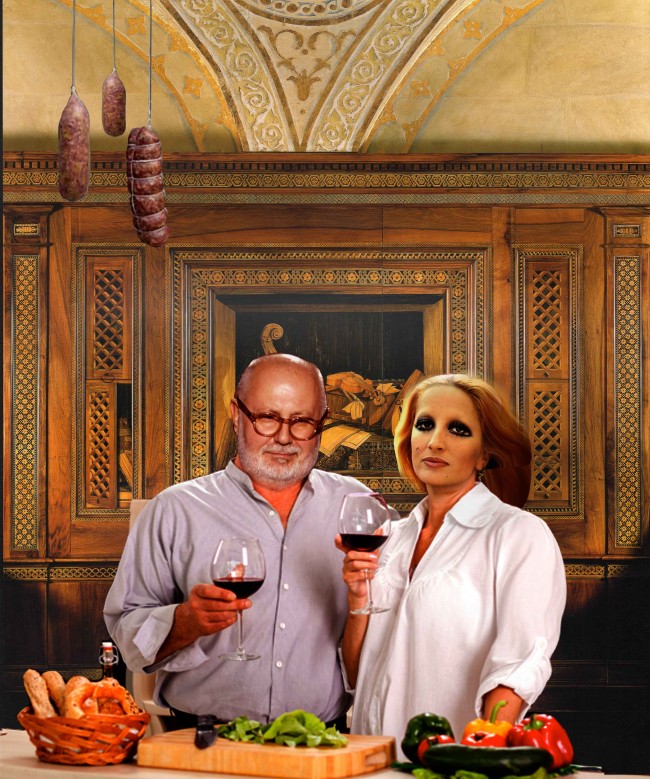

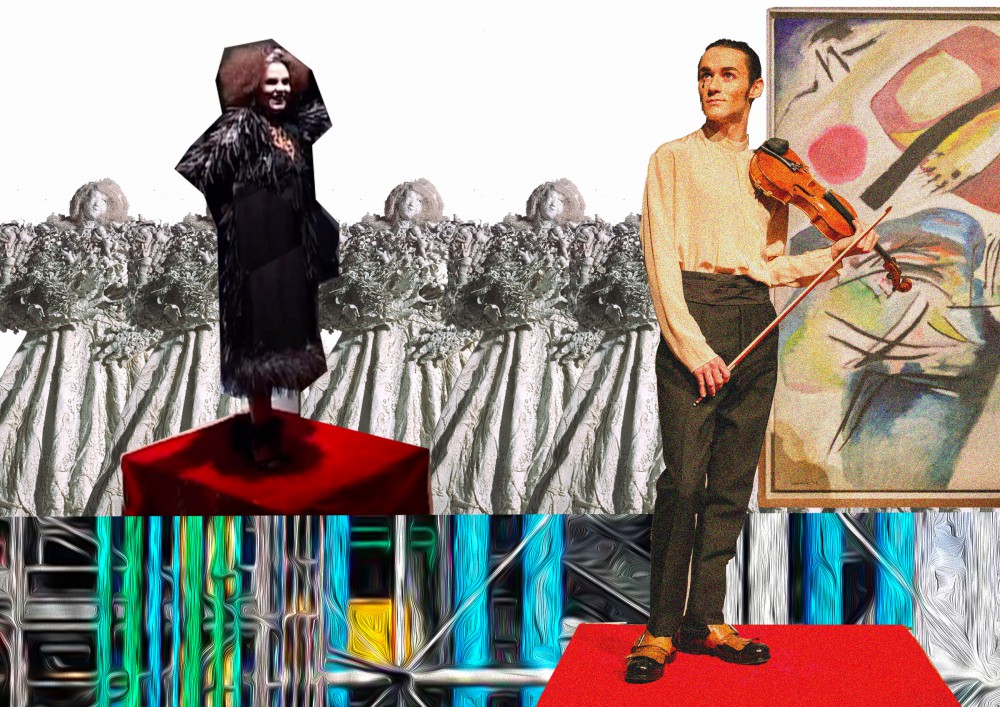

Le tout Paris (and what seemed like half of Milan) showed up for the event, which was organized by Les Amis du Centre Pompidou. In the words of Pompidou president Serge Lasvignes, and the director of the Musée national d’art moderne, Bernard Blistène, it was all a question of icons. Vezzoli had chosen 14 “iconic” works currently on display in the Modern collections, which he paired up with iconic personalities from the past — Madame de Pompadour, Jean Cocteau, Elvis Presley, etc. — and musical icons — from Verdi and Puccini to Jacques Brel and Judy Garland — with a little help from the singers and instrumentalists of the Opéra national de Paris: dressed by Prada, they took on the role of each personality as they sang or played the tune in question. While some of the pairings seemed self explanatory — Elvis performing Maria from West Side Story in front of Warhol’s Ten Lizes, for example, or Marchesa Luisa Casati giggling Offenbach’s Je suis un peu grise (“I’m a little tipsy,” from the operetta La Périchole) in front of Niki de Saint Phalle’s La mariée — others were more elusive. What was the connection between Madame Moitessier — the Second Empire society hostess portrayed by Ingres in 1856 — and Sylvia von Harden, the Weimar-era journalist so unflatteringly rendered by Otto Dix in 1926? The music gave us the clue: Tu che di gel sei cinta (“You who are enclosed by ice”) from Puccini’s Turandot (a tale of a terrifying Chinese princess who sets her suitors riddles and has them executed when they fail to provide the right answer). But why was the notoriously homosexual Count Robert de Montesquiou singing La donna è mobile (“Woman is fickle” from Verdi’s Rigoletto) to Francis Picabia’s naked Femmes au bull-dog? Heavy irony one presumes, just as in the coupling of Gertrude Stein with Marc Chagall’s Bella au col blanc (Bella appearing like a very idealized version of Alice B. Toklas) to the tune of Jacques Brel’s Ne me quitte pas. On an art-historically ironic note, Christian Schad was paired up with Kandinsky’s Mit dem schwarzen Bogen: although influenced by Kandinsky’s expressionist abstraction in his youth, Schad’s Neue Sachlichkeit work, which made him famous, took the complete opposite tack with its cold realism inspired by the Renaissance. Kandinsky’s canvas shows a rainbow (Regenbogen in German) of colors organized around a series of black arcs (Bogen), and it was thus with Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of Oz that the painting was serenaded…

Mixing with these historical icons was a whole host of present-day idols — Catherine Deneuve, Michèle Lamy, Carole Bouquet, Olivier Rousteing, Anna Cleveland, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and a shrieking gaggle of splendid drag queens all showed up — making the evening into a multi-faceted Gesamtkunstwerk of high and low culture and all the arts — rather as Charles Garnier intended for his celebrated Opéra, where the audience and the clothes they wore were just as staged as the singers who were actually performing. For it to be a true Gesamtkunstwerk à la Garnier, there had to be dance of course, which was duly provided by a late-night disco on level six. DJed by Vezzoli and Florian Sailer, the set mostly consisted of fabulously cheesy classics from the past 40 years that got the crowd bopping away with delight, fueled by the copious spirits on offer at the open bar. There was something intensely elegiac in this orgy of nostalgia, both on the dance floor and during the performance, which pushed the soirée far beyond the mere sum of it parts and made of it a reflection on the history of the Centre Pompidou itself, and the bittersweet regret of what might have been. For while Beaubourg, as it’s locally known, is principally home to a modern-art museum — with all the institutional, bureaucratic, fixed-and-rigid connotations that term implies — things weren’t originally meant to be that way. The 1971 competition brief called for a multidisciplinary building that would be a place of happenings and production, a constantly changing, adaptable center of public participatory activity (the presence today, on levels two and three, of a large public library is a dangling plot line from that narrative). And both Beaubourg’s initial program and its Piano-and-Rogers building were directly inspired by a legendary but never-realized British proposal: Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace of 1961.

“Choose what you want to do — or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle tools, paint, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favorite tune. Dance, talk, or be lifted up to where you can see how other people make things work. Sit out over space with a drink and tune in to what’s happening elsewhere in the city. Try starting a riot or beginning a painting — or just lie back and stare at the sky.” So read the publicity pamphlet for the Fun Palace, which featured drawings by Price showing a structure of steel gantries from which all sorts of equipment and spaces could be hung, linked by giant escalators — pretty much exactly what Piano and Rogers initially proposed, since their exoskeleton was intended to allow the plugging in and out of different units, as well as the display of billboards and neon advertising. While his carte blanche didn’t stretch to modifying the building, for the space of just one evening Vezzoli brought something of the original Centre Pompidou-Fun Palace dream to life. Packed with the “quivering of a whole crowd which observes and knows itself observed” (as Garnier described his Opéra), it became a pure palace of entertainment, where the erudite and the popular commingled amorously, embracing the entire city of Paris from the outdoor sculpture courts, which inevitably became giant smoking terraces — like the patios of a collective Case Study House, suspended over Paris just as Pierre Koenig’s House No. 22 is suspended over L.A. Of all the many types of nostalgia, among the most powerful is that for what came just before or around our birth (whence millennials’ obsession with the 80s), which for Vezzoli (born 1971) would mean that seemingly sunny neverland of post-war-economic-miracle optimism, the trente glorieuses that, before they ended in a bang with the first two oil crashes and Italy’s anni di piombo, produced the heyday of la RAI (the subject of his most recent show at the Fondazione Prada), the California of Hockney’s A Bigger Splash (currently on show at Beaubourg), or the France of Pierre Paulin, Concorde, the Citroën DS, and a thoroughly Modernist-minded president named Georges Pompidou

Text by Andrew Ayers. Collages by Carlo Hunbrach.

For more images of the performances click here.