THE SHED: The Morning After With Liz Diller

After years of dreaming, designing and building, The Shed is finally a reality. The spectacular multi-use arts and culture facility in Manhattan’s new Hudson Yards district was the product of a team effort, bringing together the firms of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (they of Manhattan’s High Line Park and LA’s Broad Museum) and the Rockwell Group (known for interior environments of high-end theatricality, both of the commercial and actual theatrical varieties) as well as a host of engineers, consultants and specialists — all key players in realizing the novel, improbably mobile structure, its enormous shell sliding back and forth along steel rails at the push of a button. But of all the players involved, there is one for whom the project’s completion seemed an especially personal moment. “I got very teary,” says Liz Diller: 14 hours into the project’s opening event on April 5th, 2019, the co-principal of the New York firm suddenly recognized that her “baby,” as she calls the building, was now alive and kicking, and crawling off into the world.

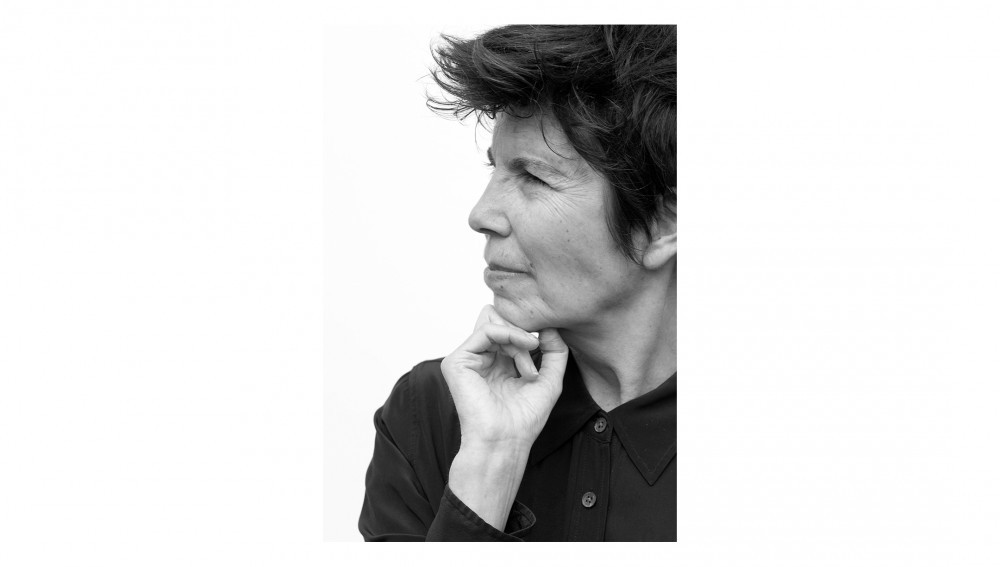

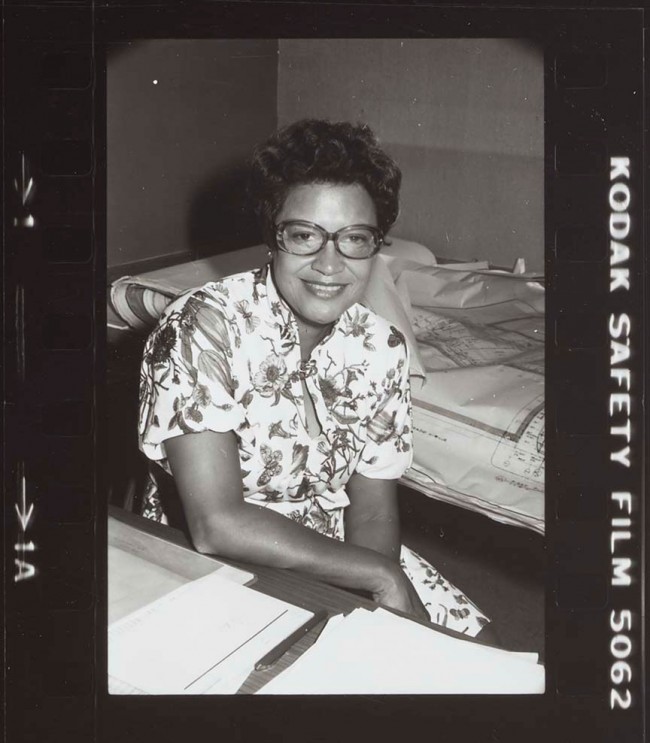

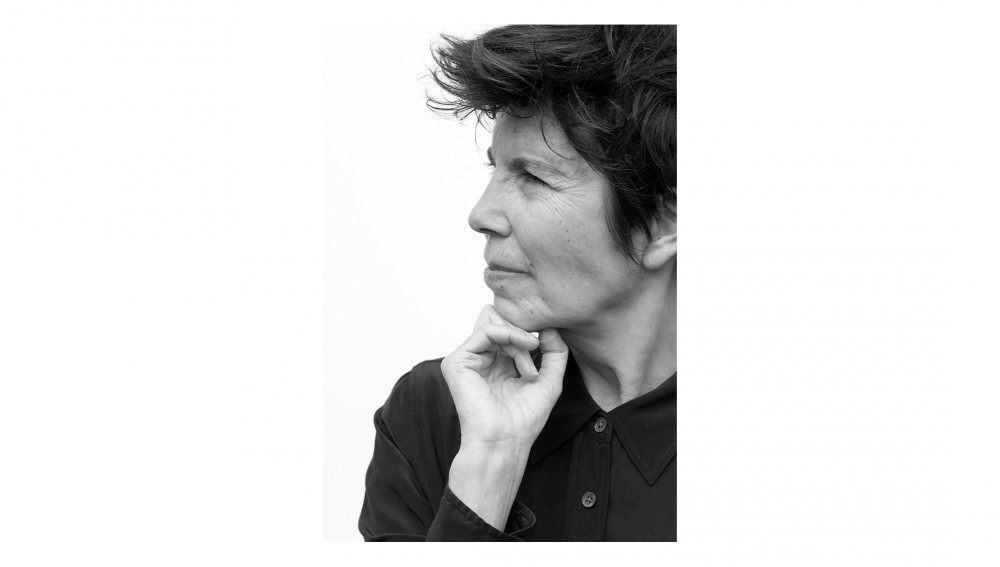

Liz Diller photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

Recovering from the festivities the following day (“At 10:45 PM,” she adds “my body just fell apart”), Diller now found herself in a curious position. She and her collaborators had been inspired in their concept and design for The Shed by Cedric’s Price’s celebrated Fun Palace proposal of 1961: a vision of architecture as pure potential, Price’s plan called for a simple frame and service infrastructure, supporting a space that could then be endlessly reconfigured according to the whims of its artist-users. The architect, in this scheme, was a sort of clockmaker god, setting the wheels going and then granting free will to humanity; since the project was never built, however, Price never had to cope with how users might feel about his creation, or how they might need his help in changing it. Taking up where the Fun Palace left off, The Shed is now a test case, not just for its designers, but for the whole ideological proposition that Price first advanced almost 60 years ago. And so — for Diller in particular — the question becomes: What now?

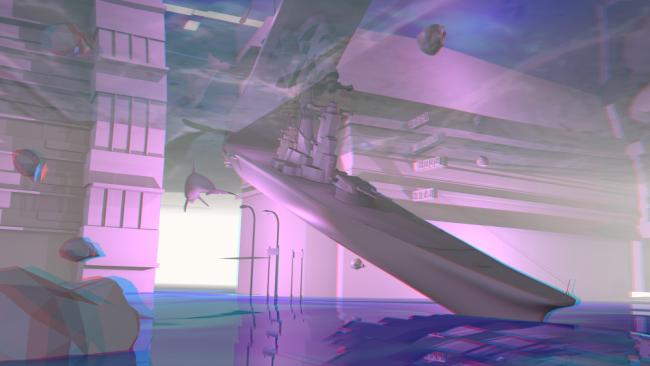

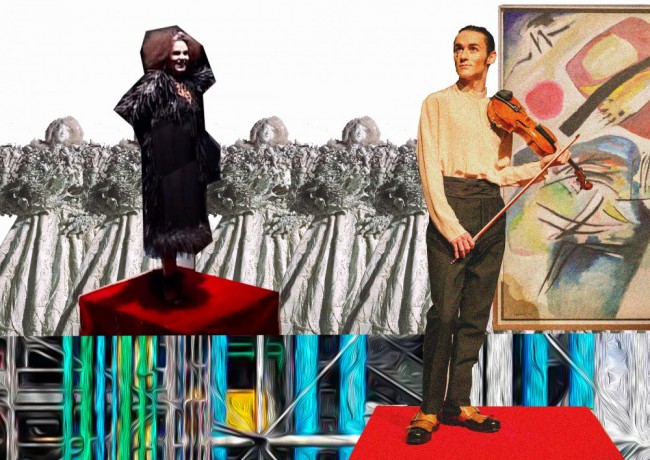

Reich Richter Pärt, immersive live performance installations exploring the shared language of visual art and music, premiered April 6, 2019, as an opening commission of The Shed in its Level 2 Gallery. Features music composed by Arvo Pärt, performed by Choir of Trinity Wall Street, directed by Julian Wachner. Images © Gerhard Richter 2018 (28112018). Photo by Iwan Baan. Courtesy The Shed.

There was a lot going on at The Shed during opening day — multiple music performances, talks with curator Alex Poots, the opening of the Gerhard Richter exhibition — was that the kind of simultaneous functionality what you envisioned?

Yes, it was a real validation to sort of see how curators and artists are able to deal with the space. We didn’t even know what all else was happening! And as the organization moves ahead with more programming, different aspects of the building are going to be utilized more and more and more. This group of artists actually started their work before they got into the building — all they saw was drawings and models. And now they’re in there and they’re saying, Wow, we all have this other potential! This bigness, this huge footprint! I think we’re going to start to see a kind of back-and-forth between the building and the users. I feel like their first impulse, was We have this toy, don’t tell us what to do; I would assume that they just have to get familiar with it, see how it endures with several successive shows. The project has been so collaborative, across many fields, that it is going to be an open discussion about it. The first order of business is just to get it as much done as possible in these next weeks and months. The building has a kind A.I., and it’s going to get smarter as it goes along.

So what is your role likely to be going forward?

Well, first of all, you know we finish it. There’s a lot of details work still to do, and we have to work on that. I think that as the project unfolds, so will the needs and desires of the artist and curators. I hope that the building’s logic allows a lot of things to happen. I’ve already seen a couple of things I think we should be thinking about changing. I would love to continue to follow the progress, and help the building adapt to whatever needs might arise. Also, I have to say I’m so connected to this project that I really want to continue to be engaged. But we’ve never had a formal discussion about what comes next.

Liz Diller photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

There kind of isn’t a roadmap for a building like this — it’s such an unprecedented typology. How do you even do post-completion follow-up?

We do have a history of sticking with our projects even in unconventional ways. Besides doing the new chunk of High Line, we also did the Mile Long Opera last fall, a live performance within the park itself. We recognized that that public space could be a place of creative reflection, to say something about the city as a whole; there was really no better spot that we knew that we knew of, and so we wanted to do that there. And with The Shed, there might be similar opportunities for involvement. We are of course going back and doing the conventional post-occupancy response stuff, but I can’t predict the next steps. The typical follow-up is just standard good practice, though how we go further is a good question. Naturally we’re going to see everything, every performance — I want to see it in action, and just appreciate it from the point of view of the audience, after having tried to imagine it from all different perspective, from the operations perspective and so on. There’s no one way to use the building, and we’re just excited to see what happens.

Evening view of The Shed, from 30th Street. Photo by Iwan Baan. Courtesy The Shed.

Text by Ian Volner.

Portraits by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.