Peggy Guggenheim, Inadvertent Patron Of Avant-garde Architecture

When you pass Peggy Guggenheim’s former Venetian home by boat, expect a rather enthusiastic greeting from its terrace. Standing, in permanence, on the edge of the Grand Canal at the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, is Marino Marini’s sculpture The Angel of the City. It is a bronze horse and rider — a nude, fully erect rider that is, whose arms, in Guggenheim’s own words, were “spread way out in ecstasy.” Both his eyes gaze upwards to the heavens, but his (once removable) phallus is aimed out across the waterway busy with passing tourists and locals alike. The member points toward the grand Palazzo of the Prefettura di Venezia, and has done since first being installed in the autumn of 1949 — quite a sensation at the time, as it remains today.

Marini’s sculpture is also, incidentally, symbolic of two themes that pervade tales about Guggenheim: sex and art. Allegedly she had quite a lot of both, resulting in the American art collector, bohemian, and socialite earning a reputation as the “Mistress of Modernism.” This moniker, however, impressive as it may be, does not do Guggenheim justice. It neglects to mention her indissoluble influence on Venice and its post-War rebirth as well as her impact on the architecture of the day. Guggenheim, who became an honorary citizen of the city in February 1962, is not only one of the most influential patrons of the art in modern history, but also a patron to one of the most illustrious cities in the Western world. Guggenheim was instrumental in reasserting Venice as an artistic and architectural hub in the late 1940s.

Poster for the 1948 Venice Art Biennale, the first after the end of the Second World War.

An important and undertold chapter in Guggenheim’s story is her exhibition at the 1948 Venice Art Biennale, a joint effort with architect Carlo Scarpa. A new exhibition paying homage to this collaboration is helping to revise Guggenheim’s legacy spotlighting how she helped foster some of the most admired architects of the time and how she greatly influenced radical experiments in exhibition design. 1948: The Biennale of Peggy Guggenheim, running May 25 to November 25 at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Guggenheim’s Venice home converted into a museum, celebrates the 70th anniversary of Guggenheim and Scarpa’s exhibition.

Guggenheim first appeared in Venice in 1947, fresh after the Second World War. Venice emerged from the war in far better state than elsewhere in Europe — largely free from physical damage, with only its surrounding industrial areas on the mainland bombed and destroyed. The crisis Venice faced was instead one of identity. For a city that remains very independently-minded, and had been quite accustomed to being internationally revered for its beauty and wealth, it felt the need for a healthy dose of what we’d now call “place-branding” in the aim of asserting “soft power.” Venetians were known for art, culture, talent, and taste, and they were determined not to let that reputation slip. When Guggenheim moved to Venice she was already a known entity in the art world having run the influential New York gallery The Art of This Century (and also having just recently divorced Max Ernst.) But it was in Venice that she’d really make her mark. At the time, the Italian city’s first mayor after liberation, Giovanni Ponti set about using art as a means to restore the city’s sense of pride, organizing art exhibitions to showcase the past and present of the city’s artists. A natural crescendo was to be the 1948 Biennale of Art, where the city would be on stage for the world. It was right at the moment the city was preparing for this monumental event that Guggenheim swept in.

The 1948 Biennale was set to be Venice’s grand return to the cultural world — it was to be the first since 1942 as the biannual event having been halted for the latter years of the war. Ponti, who had become president of the Biennale, and Rodolfo Pallucchini, its secretary general, sought to use the Biennale as a place to explore and promote the centrality of Modernism to the continent, drawing from the artistic centers of the time, Zürich, Brussels, Amsterdam, and most importantly Paris. Many of the greatest living artists were exhibited that year, including Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Mirò, Piet Mondrian, Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh. It was a heroic effort.

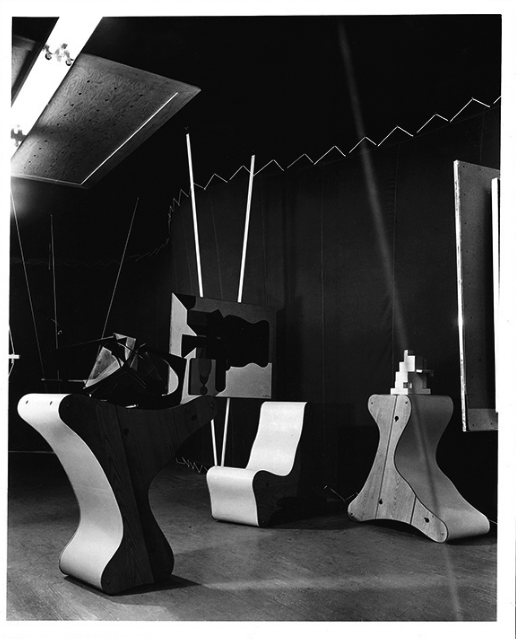

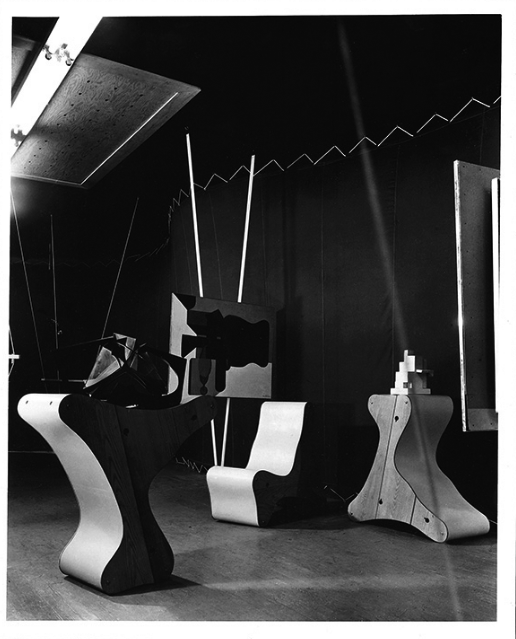

Photograph by Berenice Abbott of architect Friedrich Kiesler’s installation at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery in 1942. Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Importantly, this was also a moment of architectural revision, as well as a period marked by an incredible openness to new approaches to displaying works of art. And, Italians were leading the way. There was a desire to again make museums places of lively creativity; and, in terms of the Biennale itself, national pavilions ceased to relate to national style and began to explore architecture in new ways. The key experimenters of the time remain central names to Italian architecture: Carlo Scarpa, Franco Albini, and to some extent also Lina Bo Bardi, who left for Brazil in 1946. And so, for 1948, there was great expectation of not only what would be presented, but also how.

Peggy Guggenheim could not have been more perfectly placed than to be in Venice at this moment. She was a pioneering supporter of great Modernist artists, and she was notably open to very radical exhibition display, given her avant-garde collaboration with Austrian-born artist-architect Frederick Kiesler who designed The Art of This Century, which ran from 1942 to 1947. Kiesler and Guggenheim pushed the boundaries. In four galleries — the Abstract Gallery, the Surrealist Gallery, the Kinetic Gallery, and the Daylight Gallery — various architectural and design conventions were wiped clean, making way for new approaches to display and presentation. Walls were made of ultramarine canvas, or curved and painted black, making the viewer feel more like they were in a converted submarine than a midtown Manhattan gallery. Art was not simply hung on the wall. It was displayed using Kiesler’s “Correalist” furniture as easels, on massive spars protruding from the walls, or on ropes pulled taught between floor and ceiling. In some cases, visitors were invited to — quelle horreur! — interact with the art. At others, the lights of the gallery were set to flash erratically. It was part art gallery, part psychedelic avant-garde immersive experience. Needless to say, it was a non-commercial gallery.

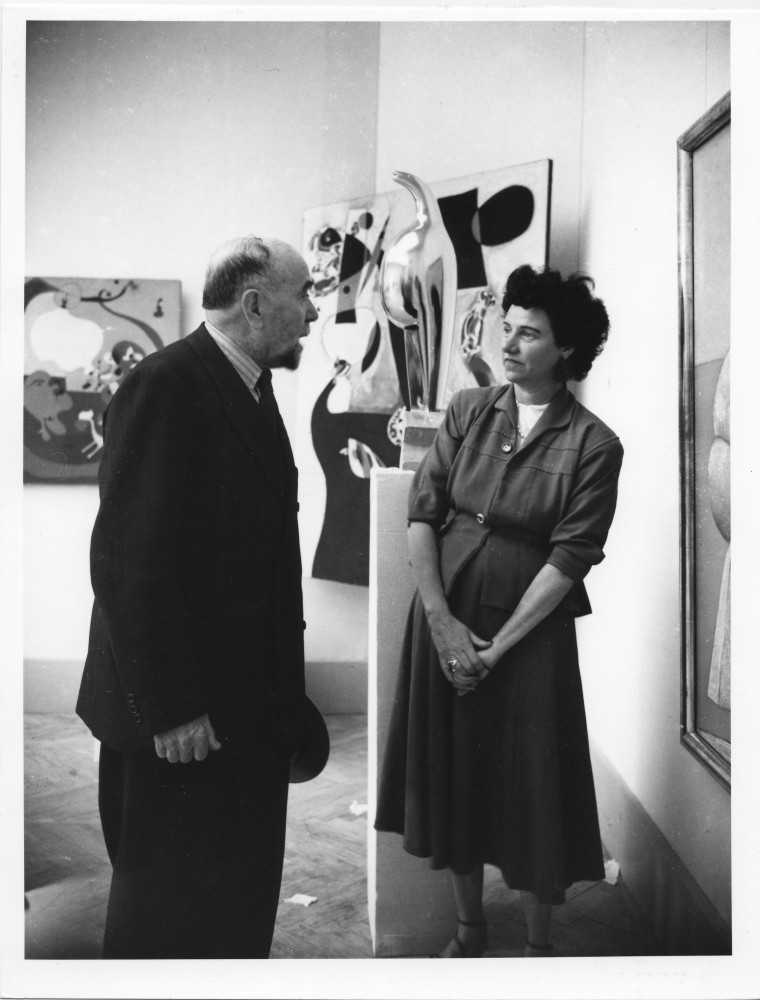

Peggy Guggenheim during the preparation of the Greek pavilion, where she exhibited her collection, at the XIV Venice Art Biennale, with Dutch Interior II by Joan Miró, left, 1928, Seated Woman II, center, 1939; 1948. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, photo Archives CameraphotoEpoche, Venice Savings Bank donation, 2005.

In Venice, Guggenheim’s reputation, and that of her art-collecting family, preceded her. As soon as she arrived in 1947, she ingratiated herself to some of the most important artists in the city — the painter Giuseppe Santomaso being the most instrumental of her new friends. The story goes that Guggenheim had introduced herself to him at a bar, the Sant’Angelo. It was Santomaso who then introduced Guggenheim to Rodolpho Pallucchini, and opened doors for her to exhibit in the Giardini. It was rare for a private sector entity like Guggenheim to have this opportunity as the Giardini is made up of national pavilions. Guggenheim was given use of the Greek Pavilion, a beautiful brickwork building with a triple-arched loggia. Unfortunately the Greeks at the time were in the midst of a civil war. Guggenheim was assigned by Pallucchini the then-41-year-old architect Carlo Scarpa to design the exhibition. Among the Modern architects, none today are as as tightly associated with Venice as Scarpa; Guggenheim herself came to refer to him as “the most Modern architect in Venice.” That year for the Biennale, Guggenheim’s pavilion was one of several projects that Scarpa worked on — another notable collaboration was Scarpa’s exhibition for Paul Klee.

For Scarpa, work with the Biennale would have been an immense opportunity. At the time, he had had few major works in his portfolio. It was an opportunity that he clearly took advantage of, 1948 being the start of collaboration between Scarpa and the Biennale that would last 24 years, and would produce such gems as the Biennale’s entrance gates and the Venezuelan pavilion. With the Biennale of Architecture only formalized in 1980, the role of the architect in the Biennale of Art was of much greater importance than today. Back then, exhibitions were seen as a principal platform for the architect's discipline.

Born in Venice, Scarpa was a skilled craftsman in furniture-making and glass — as you might expect given his birth city. He admired architects who valued craft, notably Frank Lloyd Wright. His reputation today is that of a man incredibly adept at interventions made to existing buildings — a perfect skill for the stately buildings that existed on the Biennale grounds at the time. His restoration of Castelvecchio in Verona (1958–74) is considered his masterwork in this respect. This expertise of Scarpa’s emanated from an interest in what MoMA curator of architecture and design Barry Bergdoll calls “a dialogue between a building and what was added to it.” Scarpa’s ability to create this conversation between old and new is a thread that continues through his body of work and influenced other architects such as Franco Albini.

Peggy Guggenheim on the steps of the Greek pavilion at the 24th Venice Biennale of Art in 1948, where she exhibited her collection. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, photos Archives CameraphotoEpoche, Venice Savings Bank donation, 2005

Scarpa’s inventive approach made him a great match for Peggy Guggenheim. She similarly understood the way an art was in dialogue with its surroundings. For her, the “framed picture” and the “sculpture on a pedestal” were not the default forms of display. Guggenheim truly lived with art. One example of the fluidity with which she enmeshed her life and her love of art is a silver headboard she commissioned Alexander Calder to create for her bedroom. Art in Guggenheim’s world could be touched and used. Art for her should be integrated in design and architecture. And, importantly, and in a pure vein of the Modernist movement, it was about self-expression — as such, it didn’t have to answer any questions, rather it could pose them.

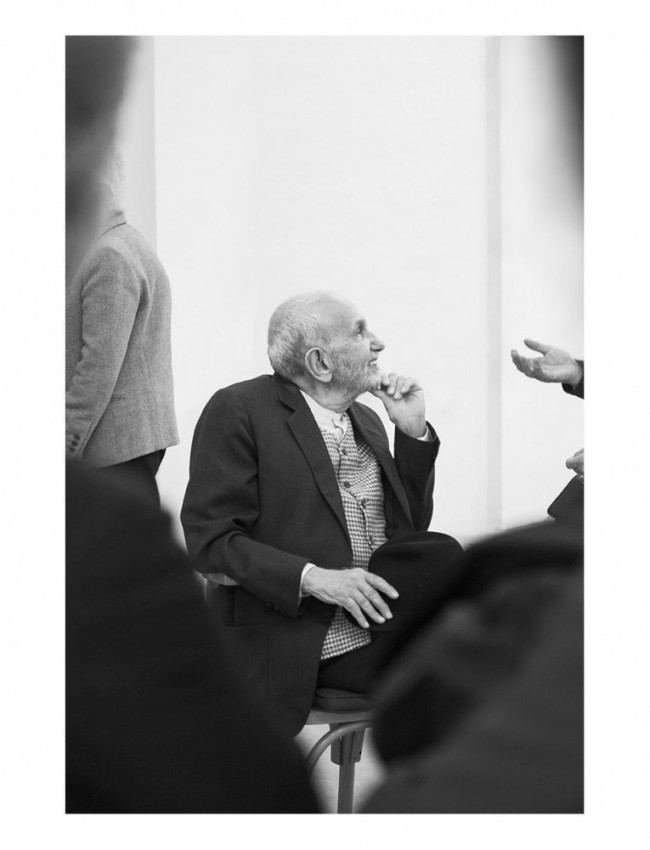

Guggenheim and Scarpa were both interested in imagining new ways one could display and encounter works of art. We see in Scarpa, whose legacy has never really faded and only grew in in the 1990s, “someone who has a dialogue between modernism and craft, and,” says Bergdoll, “interesting to people who wanted a sense of individuality, a sense of artistry, a sense of signature — but yet couldn’t really embrace Modernism.” Scarpa focused on materials and assembly; certainly this would have been apparent and incredibly appealing to Guggenheim at the time. (As a slight aside, it’s interesting to note that Scarpa had at least tried to solicit the help of fellow architect and designer, Ettore Sottsass, who was barely 30 at the time, in creating the exhibition for Guggenheim. It remains unclear whether Sottsass ever took him up on the offer. All we have are letters from Scarpa to Sottsass, and then from Sottsass to Pallucchini, all suggesting that the joint effort would be a nice idea.)

Peggy Guggenheim with the painter Arturo Tosi in the Greek Pavilion of the Venice Art Biennale 1948. In the background: Two works by Joan Mirò, Interior of the Netherlands II, 1928, and Donna Seated II, 1939, as well as the statue of Constantine Brancusi Maiastra, 1912. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, photo Archives CameraphotoEpoche, Venice Savings Bank donation, 2005.

Guggenheim and Scarpa’s installation of 136 works of art had to be done in an astonishing three days, yet ended up as one of the most popular and groundbreaking exhibitions of the year. And, as the works for the United States pavilion had not yet arrived when the Biennale opened, Guggenheim also became a de facto representative of the her home country, in a year when many national pavilions also remained closed. Seventy years later, the results of Guggenheim and Scarpa’s collaboration for the 1948 Biennale still rings of experiment and progress. It was an exhibition that few since have rivaled in Venice. Gražina Subelytė, who curated the foundation’s current exhibition that pays homage to 1948, sees the interplay between Guggenheim and Scarpa as a genuine collaboration. Various artistic movements were distinguished in the display — early European abstraction, Surrealism, American abstract expressionism, something which Scarpa would not have been familiar with. Yet, throughout the installation, there was “a genuine architectural touch,” says Subelytė. For instance, certain paintings were arranged one above the other: a 1938 composition of Mondrian sat at the center of a group of other paintings that seem to grow from it, scaling the walls around it in an organic pattern. Another decision was made to hang some paintings in the very corners of the room, something Subelytė attributes to Scarpa, and that was antithetical for the time.

For both Guggenheim and the majority of critics, the Biennale collaboration with Scarpa in the Greek pavilion was a triumph. In her 1960 autobiography, Guggenheim notes, “My exhibition had enormous publicity and the pavilion was one of the most popular of the Biennale.” Similarly, in one review, in Il Corriere Democratico newspaper, critic Garibaldo Marussi raved that “the Guggenheim collection contains the entire explosive potential of the XXIV Venice Biennale.” While Guggenheim’s impact on the arts is undisputed, her influence on architecture is a lesser known part of her legacy. It’s a pivotal role that she continued to play until her death and beyond, as the lasting relevance of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection attests. Post-war Venice provided a space of great possibility during which many boundaries were pushed (some of which we’ve since seem to have reconstructed). It is no coincidence the so-called “Mistress of Modernism” was very much at the heart of it all.

Text by David Michon.

All photographs courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.