INTERVIEW: Frida Escobedo on Tiles, Skincare, and the Joys of Voyeurism

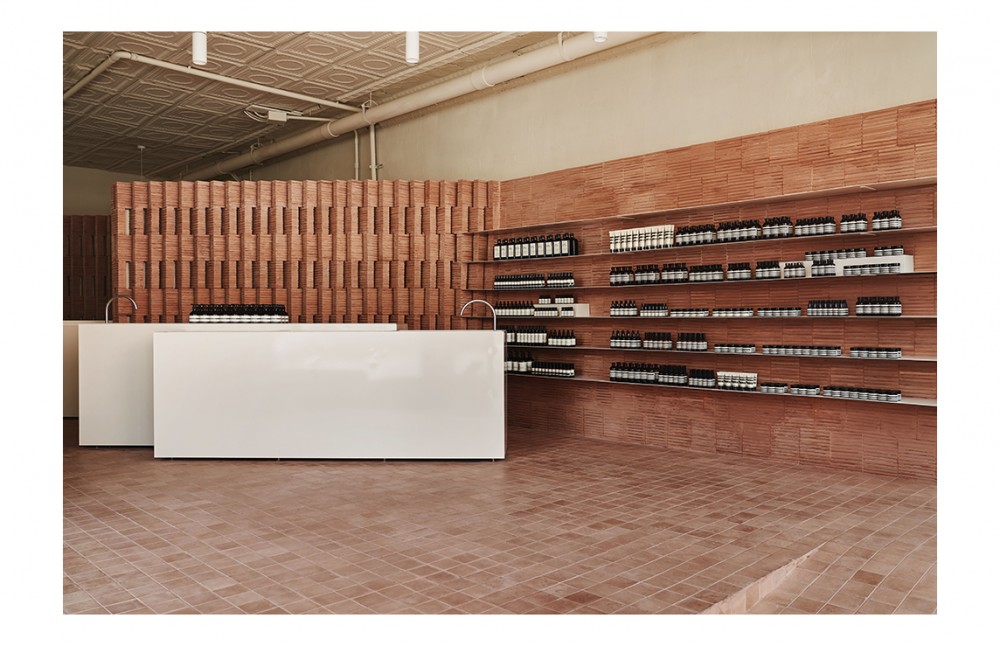

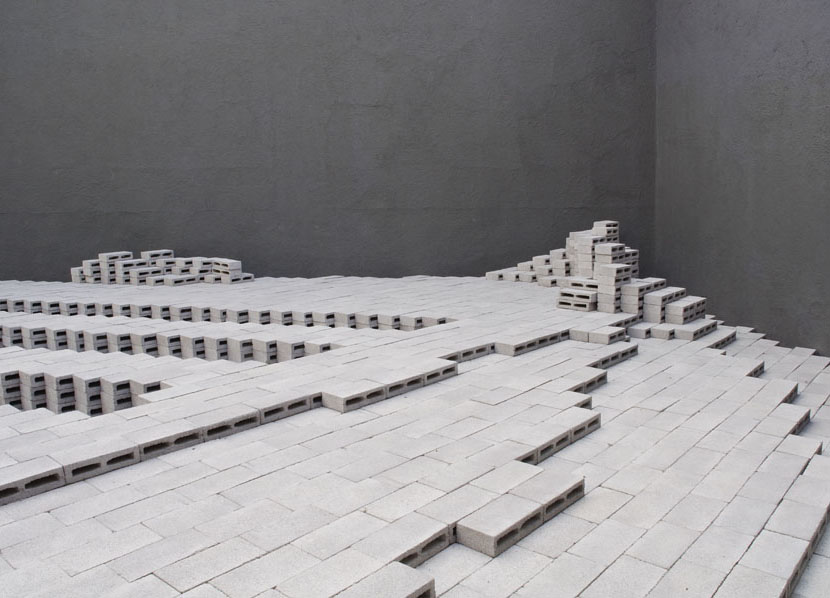

Aesop store in Park Slope, Brooklyn (2019).

Last summer PIN–UP caught up with Mexican architect Frida Escobedo just as her design for the Serpentine Pavilion in London was poised to open. Escobedo is the youngest architect and only the second ever woman to win the prestigious commission, a three-month summer activation of the palace-adjacent Kensington Gardens, awarded annually since 2000 by Serpentine Galleries. For the contemplative temporary structure Escobedo interlaced locally sourced tiles in a woven tapestry-like style, allowing for the dance of light and shadow while a triangular-shaped pool inspired reflections. Since the pavilion closed in October 2018, Escobedo has been juggling countless projects taking her all over the world. We met with her again during a recent stay in New York, for the opening of a new Aesop store in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, the seventh location she’s designed for the Australian skincare brand.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP.

You’re a bit reluctant to do commercial projects and the stores for Aesop are the only retail spaces you’ve ever done. What gives the brand the honor?

Aesop is different because they allow us to experiment with things. They didn’t ask us to create a corporate identity or signature identity. And if you look at all the stores that we’ve done with them, each one of them is completely different. That’s why we keep working together.

What is special about this one here in Park Slope?

It used to be a cat clinic. The first time we came to see the space it was full of partitions, little rooms, and small cubicles to treat the cats. There was a technical complication because all the plumbing was in the center. So that was quite a challenge. In the end it worked out well because we were able to create these faults and pockets that broke up the space. We also redid the entrance and made it bigger, stretching over the whole corner. Now the doors almost embrace you with open arms. In the traditional store layout you have the sales counter near the exit; here the point of sale happens later, deeper inside the space, so you get to experience the products first. The idea is that you move around the space, look around, try something here and there, and the room draws you further in.

Which of the existing elements did you keep?

There were these beautiful layers of history that we discovered: the drop tin ceiling, which was really interesting and beautiful; the height is amazing. We painted the original brick wall. I think it’s pretty obvious when you walk around Park Slope, there is a tradition of intricate brick walls and facades, many different iterations of lines and patterns. I immediately felt this tradition needed to inform what were we doing. This was a material we wanted to work with because it connects to the surroundings.

The brickwork you installed inside the space has a different feel than the one used for the façade, for example.

We didn’t want to use local materials because it felt a little bit artificial to bring that back. But we also didn’t want to use industrially made material either. So we got in touch with a company in Mexico that I’ve worked with in the past and we produced these tiles with them. They’re handmade from compacted earth so it is more about the process rather than efficiency; they took over eight weeks to make. The pigment is natural from the soil sourced from the Mixteca region in Oaxaca — a bright, beautiful red color, very intense. When you mix it with other components to make it more stable, it turns into this soft hue, like a blushy pink. Both the production and installation are part of the cultural conversation we wanted to create.

Tell me about the structure of the walls.

It was inspired by the local architecture, these patterns, this ordinance in the façades. It was almost like twisting the brick. We were using the same raw materials, but just offsetting them in little shifts so they would create a different rhythm. I always think of this type of texture as weaving. Kind of a binary combination: one on, one off. The result is a complex structure that plays with light, and as you move through, it changes, opens up.

Aesop store in Park Slope, Brooklyn (2019)

How did your collaboration with Aesop start?

In 2013 we did a temporary store inside a gallery space called Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn, not very far from here. The interesting thing about that collaboration was that we could investigate and ask questions like: “What is a pop-up store? What does this time limit mean?” Back then we played with the notion of temporality and installed this shifting ornament made of sand. I thought that it was really nice because they allowed us to experiment with materials, with techniques, and with the context of the space.

Is there an Escobedo signature in these spaces?

I don’t know. Maybe I should ask you that question. What do you recognize as Escobedo language?

The idea of temporality, which I would ascribe to your early earthquake memories in Mexico City, but also the way you treat the public and the private.

Yes. I guess retail is an interesting space because when you design, let’s say, a private house, which is a closed environment, very private. But retail is in this between-space, particularly retail for something as private and intimate as skincare.

-

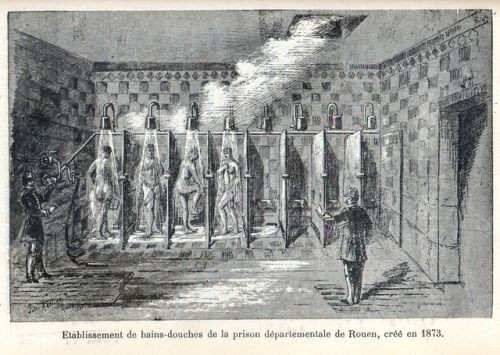

Aerial view of Frida Escobedo’s 2018 temporary pavilion for the Serpentine Galleries in Kensington Gardens, Hyde Park, Central London.

-

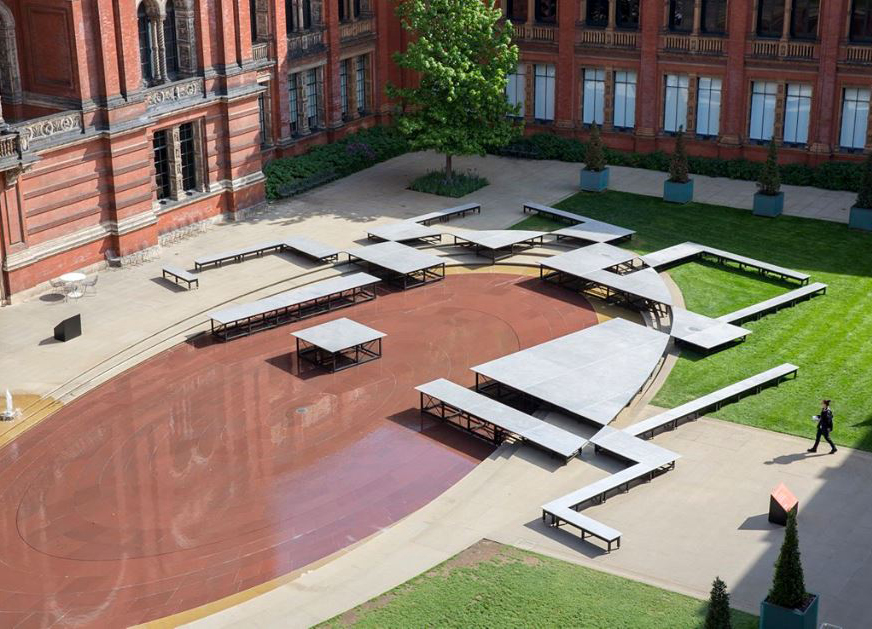

You Know, You Cannot See Yourself So Well as by Reflection, an installation by Frida Escobedo at the V&A in London in 2015. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

-

El Eco Pavilion by Frida Escobedo for the Museo Experiemental El Eco, Mexico City, 2010. Photography by Rafael Gamo.

I think questions of discretion are another Escobedo signature. You once told me you became interested in architecture as a child watching through windows people going about their lives.

My dad is a doctor and sometimes he would pick me up from school and take me to the hospital until he finished. When he had surgeries in the afternoons, I would have to entertain myself. There was this apartment building in front of the hospital, and one of my favorite things to do was to look out of the window and watch people. It was really interesting to see how each one of the apartments had a completely different life even though it was the same façade, to some extent even the same apartment. I think this was my first moment of realization that what happens inside a home depends on how it is constructed. It’s a dual thing. On the one hand it is determined by the building itself, but then all these nuances kick in. The way people decorate their spaces and how decoration is not just ornament but also an expression of who you are, your expectations or aspirations versus history. What ideas are in your head and how are they presented in the space? Watching the people I was telling myself stories about them. I was very voyeuristic.

What else are you currently working on?

We’re doing two hotels in Mexico, some private houses, and we’ve been working on the exhibition design for the Ettore Sottsass and the Social Factory exhibition, which just opened at the ICA in Miami. We’ve also been developing some furniture.

Aesop store in Park Slope, Brooklyn (2019)

What kind of furniture?

We just finished a screen, something for the bedroom. It is something our grandmothers would have had to change behind, because the idea of the bedroom as this private space for one or two people is relatively new. In our piece, you have this mirrored screen and it is transparent, so when you light it from behind, it becomes transparent and if you don’t, it remains a reflective screen. The piece allows you to both reveal and conceal. It has these different moveable elements — blinds you can adjust, which create texture. You can control the amount of light and transparency. Then you have these flexible mirror parts that can cover your face and give you something to play with proportions. It’s a really playful and fun project.

Here’s the voyeur in you again.

And the exhibitionist! (Laughs.)

Text by Eva Munz.

Portraits by Dorian Ulises López Macías.