WHITE MALE PROBLEM: A MoMA SALON ON INSTITUTIONAL INEQUALITY

This past spring, Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of the Department of Architecture & Design and Director of R&D at MoMA, began a salon themed around the “white male” explaining that the impetus for the conversation-driven event came out of anger — a response to the #metoo movement, growing fascism around the globe, and outrage-inducing statistics. The salon was the 30th in a series Antonelli started in 2012 aimed at showing people that museums “can be useful in everyday life” and “a place where one convenes to discuss even difficult topics.” And this topic proved to be the most difficult yet. In organizing the White Male Salon Antonelli’s team encountered more knee-jerk reactions than past events because the title is such a punch in the gut. You can’t help but react. Antonelli and salon producer Samantha Ozer received many refusals from the potential artists and thinkers they reached out to participate. In her opening remarks, Antonelli mentioned that many of those who demurred were not white men, a note of surprise in her voice.

Google Image search results for "CEOs" show mostly photos of white males.

The idea of stereotypes was at the crux of the event, and according to the organizers, it’s about time that we stereotype white men — though Antonelli qualified that nuance is necessary because like all identities, white men are not a monolithic group. Perhaps Homi K. Bhabha, a scholar and critical theorist, framed the subject best with a pre-recorded video, by simply asking the question “what is white male culture?” The event was preceded by a rigorous reading list, composed predominantly of articles from liberal journalism outlets with the occasional hard-hitting academic chapter. The reading list’s subthemes included: white male entitlement, power and normativity, white men in the workplace, white male anxiety and perceived discrimination, the insecure response to our first Black president, the white male online, and from white supremacy ideology to violence.

Throughout the various presentations, the audience — Upper East Side-type women wearing pearls mingling with what’s left of New York’s intelligentsia, at least the segment who decided "sure, I guess I'll go to midtown after work” — was provoked to confront some of their own biases. In recent years the narrative that systemic privileges have allowed white males to dominate the upper echelons of society, specifically the spheres of business, technology, politics, and of course art has become increasingly acknowledged in the mainstream. The bravery of the MoMA R&D department acknowledging this uncomfortable reality, reactions be damned, and in doing so indicting their larger institutional apparatus, cannot be understated. In her presentation writer Aruna D’Souza, one of the salon’s most engaging speakers, made explicit the irony of the event’s context, pointing out the problem of racial and gender inequality in the museum’s own collection and programming. While CEOs named John and Jack outnumber women CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, D’Souza noted that MoMA exhibitions by artists named Richard and Robert vastly outnumber exhibitions given to non-white, non-male artists.

Stock photograph of a white male.

As Antonelli pointed out in her opening, social and economic polarization, thanks in no small part to the information we consume in filter bubbles, results in our becoming more biased, not less. To that effect, the White Male Salon at MoMA is a step (albeit a small one) in the right direction toward revealing our biases to ourselves, holding up a metaphorical mirror and revealing things we didn't know were there, and part of realizing our less than desirable qualities is understanding that we need to change, as architects, as designers, as curators, as writers — but most importantly as members of society at large.

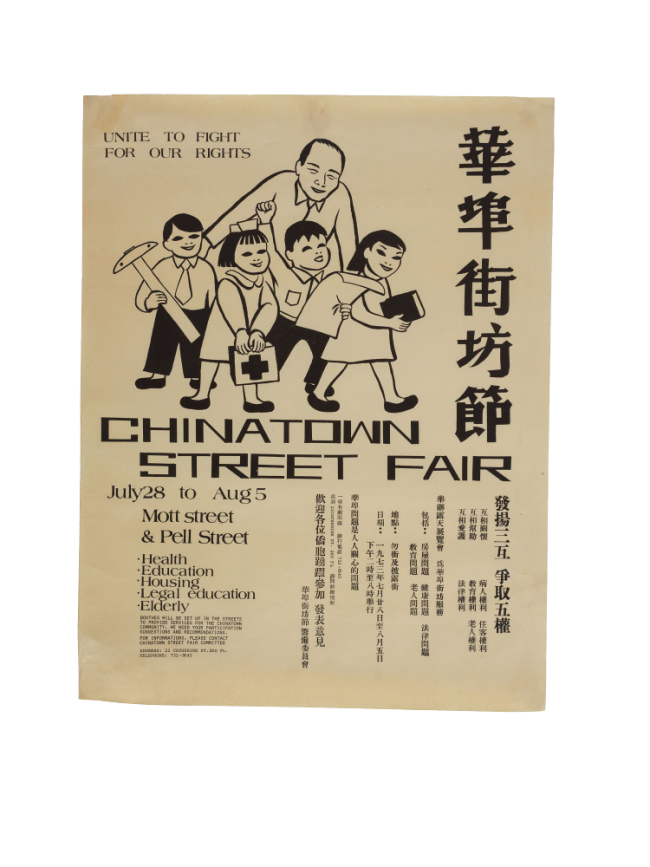

D’Souza used the groundbreaking 1994 Whitney Museum exhibition Black Male curated by Thelma Golden as a foil to ask the question “What would an exhibition called White Male include?” She referenced Pastiche Lumumba’s Woke Gentrifier Starter Pack, a brilliant détournement of Internet meme logic lodged against those who fancy themselves cultural warriors behind keyboards. As a matter of historical record, this hypothetical exhibition could include all the Roberts and Richards, but also for example artists like canonical street photographer Garry Winogrand whose work like the series “Women Are Beautiful” epitomizes the white male gaze. As a corrective counterpoint, D’Souza suggests we also include Laurie Anderson’s photo series which flips the script. In the 1970s, Anderson responded to cat calls hurled at her on the street by taking photos of her hecklers, the men’s responses included as text below each image.

Woke Gentrifier Starter Pack (2019), Pastiche Lumumba. Courtesy of the artist.

A short film by the Guerilla Girls presented during the salon can be interpreted as a warning to MoMA regarding their future exhibition programming, calling out the undeniable fact that “most of the work and most of the money in the art world go to white male artists.” A particularly incisive moment in their video presents “3 WAYS TO WRITE A MUSEUM WALL LABEL WHEN THE ARTIST IS A SEXUAL PREDATOR” for the official portrait of Bill Clinton by Chuck Close. Oof!

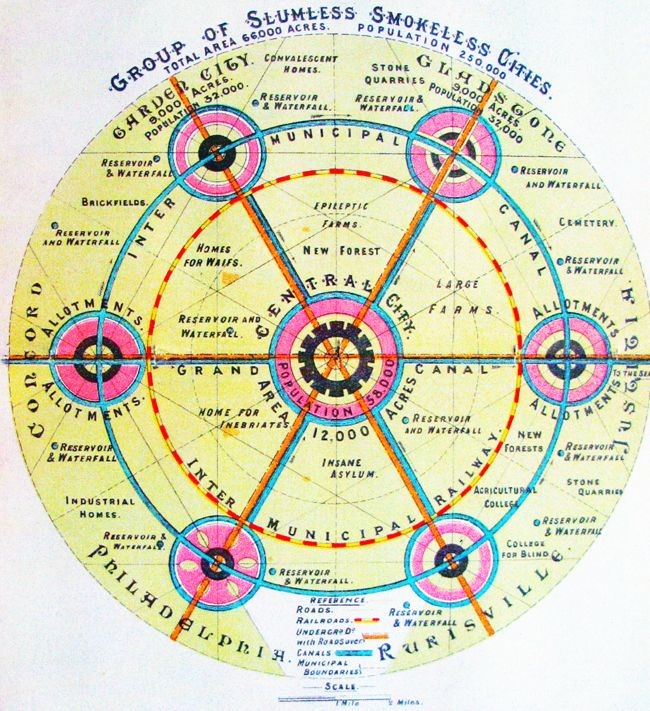

Museums, like all large institutions, are not monolithic places. In MoMA’s case, it is really the institution’s collection, exhibitions, and public programming that sets the public tone and establishes its priorities. With this in mind, would the world be okay without another Richter and Rauschenberg retrospective? After all, these are choices, not inevitabilities. There is in fact a great diversity of exciting monographic artist exhibitions scheduled for the museum’s grand re-opening this October, including Lygia Clark, Betye Saar, Dorothea Lange, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a personal favorite). Furthermore, the newly renovated museum will have dedicated spaces for the relatively recent Department of Media and Performance founded in 2013 which has been leading the way in making progressive changes at MoMA, in part thanks to a younger generation having more influence over the collection and programming. How else could the museum disrupt the status quo? The upcoming March 2020 Donald Judd retrospective could acknowledge the contributions of his women collaborators and partners. The current Lauretta Vinciarelli exhibition on view at the Judd Foundation is a fantastic example of this approach that dismantles the myth of the sole genius toiling away in his studio with his paint and canvas.

Stock photograph of a white male.

While Jean-Luc Godard (a white male) may be a problematic person to quote here, I find his words useful: “The problem is not to make political films, but to make films politically.” The challenge for MoMA R&D Salons could be formulated similarly: not to make political events, but to make events politically. The missing link between all the themes laid out — the truly foundational layer that intersects all the various sub-themes identified by the reading list and the presenters themselves — is the museum’s unavoidable financial prowess as the institution that attracts big-ticket gifts simply because of its position as elder statesman in the cultural landscape and the self-proclaimed carrier of the torch of Modernism. If the only result of a brave and risky initiative beginning to decolonize an institution is to assuage that institution's guilt about its history in creating the very thing it now seeks to undermine through performative empty gestures, then we have a problem. If that single event is the end of the conversation, it will be seen as artwashing, a counterproductive donor-mollifying one-off, a pawn in a larger conversation about cultural white supremacy. MoMA wants, needs, to be relevant and if it is indeed to be relevant, then the only way to ensure that relevance is to take concrete steps to divest from economic structures that reinforce these inequalities.

An anecdote that cuts right to the heart of the interrelated economic and racial dynamics: three weeks after the salon Antonelli tweeted an internship opportunity in MoMA’s R&D Department noting both “must be Greek or of Greek descent” and “slim salary.” In addition to flouting employment anti-discrimination laws, this “altruistic gift,” presumably from a wealthy Greek family, funds a position with a salary so meager that it requires a disclaimer from Antonelli, revealing (as the semi-anonymous Google Doc currently circulating of museum worker salaries also does) that even institutions with progressive programming quietly perpetuate white supremacy when their employees are so low paid it implies that these positions are reserved for a white male, or at least someone in the white male wealth bracket; the meager financial compensation potentially supplemented by inheritance or a trust fund.

Fyre Festival founder and felon Billy McFarland. Rich Benjamin's salon presentation discussed McFarland in the context of the luxury of failure for white males.

My own position as a white male who has had every advantage in life puts me in a somewhat ridiculous position to even write this review. Yet at the same time, perhaps someone who intimately understands the codes of this stratosphere of society, recognizes the structures it perpetuates, and wants to be an ally in dismantling it from within, has a uniquely privileged position to write from? So from a position of pre-canceling myself, read this review with a grain of salt with regards to its own problematic identity politics. Recognizing that institutions like MoMA are slow-moving cruise ships in the landscape of cultural spaces — their programming planned years in advance and difficult to abruptly change course — my hope is that if MoMA as an institution will respond to any critique at all, it might be that of a white male, politely urging in the way I know they might listen: please do better, I’ve had enough of seeing myself reflected back at me in your institution, there is no excuse. The mere act of the White Male Salon is already crucial, and productively framed so as not to alienate the museum’s donor class; but please, don’t stop there.

Text by Jesse Seegers.

Jesse Seegers works between architecture, design, writing, editing, publishing, and research practices.

Images courtesy of the artists unless noted otherwise.