INTERVIEW with MARTHA ROSLER, The Artist Who Speaks Softly but Carries a Big Shtick

Martha Rosler in her livingroom.

Martha Rosler knows that a well-formulated suggestion is far more likely to change the world — or at least someone’s mind — than any command or decree. “Every single thing I have offered to the public has been offered as a suggestion of work,” says the 75-year-old Brooklyn-born artist. Whether it’s her photomontages or videos, her sculptures or her installations, each offering retains a lively air of possibility and buzzes with the connective creative energy of a sketch — a feat made all the more impressive by her choice of subject matter: consumerism, feminism, gentrification, poverty, and war. Floating free of cynicism and buoyed by compassion, Rosler’s work can be devastatingly funny or amusingly devastating, and often both. “By boiling her subject matter down into small slices of life — indeed she often consciously mimics the look and feel of ‘high art’ — she is able to situate her work in a familiar context,” says Darsie Alexander, chief curator at New York’s Jewish Museum, where Irrespective, a survey show of Rosler’s work from 1965 to the present, is taking place this fall. “All her work still feels very immediate and urgent, especially when it comes to the omnipresent power of the media to shape public opinion and influence private reality,” Alexander continues. For this interview, Rosler took a break from completing several new pieces for the Jewish Museum show to invite PIN–UP into her Greenpoint brownstone, where we discussed her trailblazing work on housing and the built environment, and how she continues to bring the big issues home.

Stephanie Murg: Over the course of your 50-year career you’ve mastered a broad range of media, from collage, to painting, to photography, sculpture, and video. How do you decide which medium to work in?

Martha Rosler: Quite honestly I started as a painter, and those other things were a way of expressing something that wasn’t abstract, because I was trained as an Abstract Expressionist painter. So the other things were just things that artists did as a way of saying, “I actually do have something to say that can be translated into images as opposed to abstractions.” I remember being heartened by the realization that, as far as I could tell, abstract painters also took photographs, and made drawings and cartoons, and even photomontages. So gradually I realized I’d rather do those things, although I kept painting for quite a while.

Another important aspect of your work is the ability to collapse complex cultural, political, and social issues into a very personal kind of view — not necessarily the view of a single person, but making it so that the viewer gets an individualized perspective on these massive, usually faceless problems.

I think that’s a good way to put it; I like to bring issues, which are relatively abstract, down to the level of the personal. I was always interested in addressing people, primarily women but not only women, with the idea that you recognize me for other human beings. Even on the level of clothing, in thinking about my anti-war work, I was very interested that the people we were fighting didn’t look like us, and it was very easy to demonize them. So, in effect, using clothing as a substitute for humanity, for our world, there was one installation I did where I put the name, date of birth, and prisoner number of some female political prisoners imprisoned by the South Vietnamese government on American clothes (Some Women Prisoners of the Thieu Regime in the Infamous Poulo Condore Prison, South Vietnam (1972)).

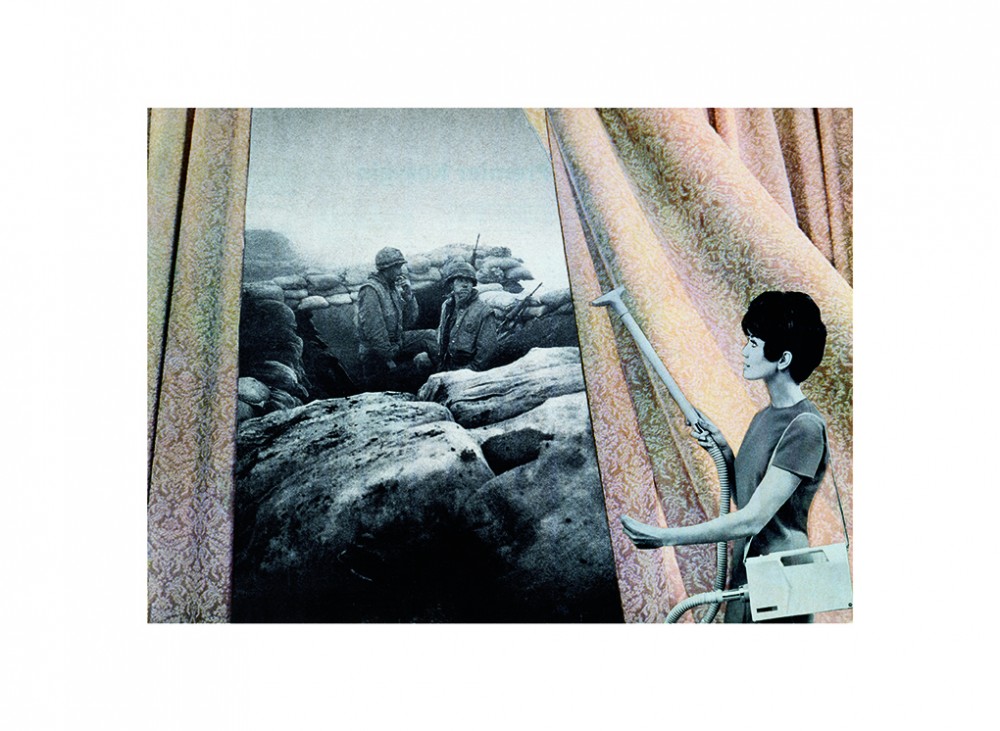

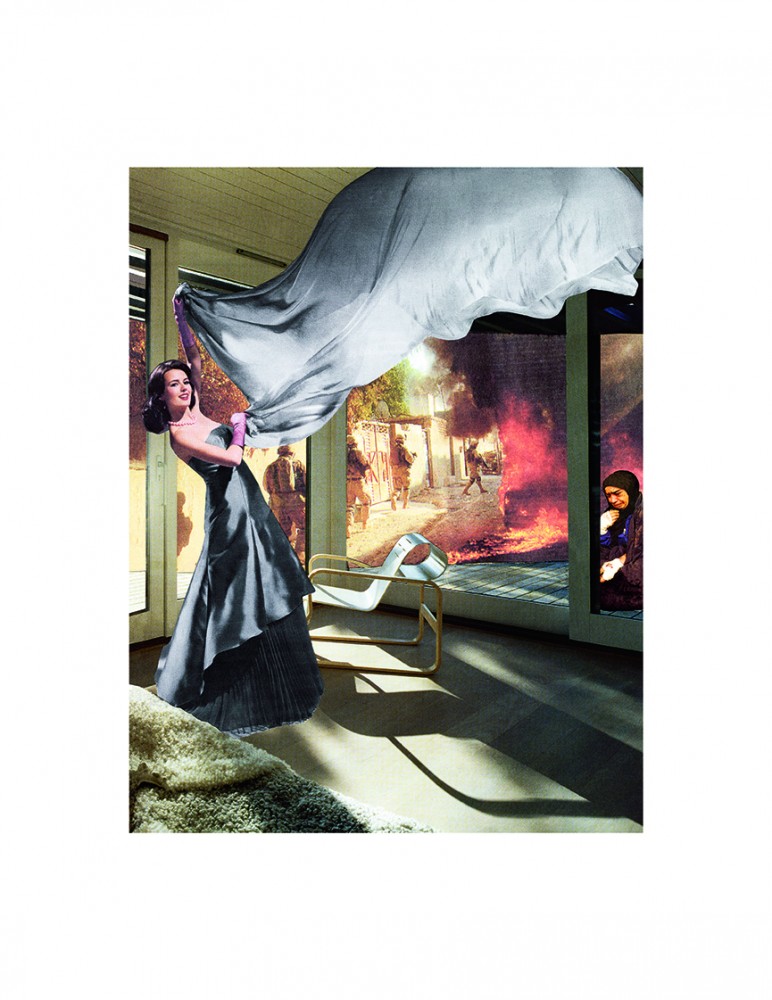

Cleaning the Drapes, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, (c. 1967–72); Photomontage. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

One of your most iconic series is House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c. 1967–72), where you brought together familiar, domestic, relatable spaces with grueling images of the Vietnam War. And you brought out a new series of work with the same title at the time of the second Iraq War (2003–08). How did you first develop the idea?

Back then, even though we had our mental boxes for what war looked like, we didn’t ever put them together with our own habitations and territory. And to be very simple-minded about it, I wanted to say, “Well it’s one world, and in fact, we here in our pretty little houses — or the houses we aspire to be in — are deeply implicated in this.” It was another form of identification for the viewer.

You first made that work almost 50 years ago, but it seems as if today when we are engaged in similar conflicts — whether it’s Syria, the refugee crisis, or even the Mexican-American border — there is still such a remove. Do you think that in our modern media age something has changed in the way we experience and understand these events?

There has been some change, but I’d like to point out that one of the biggest spurs to my doing this was that we got to see the (Vietnam) war in our homes, on TV. It wasn’t live TV, it was filmed, so it was never quite the same day that we were seeing it, but we didn’t know that, so we got to see conflict with dinner! And that was why the war was called “the living-room war.” So it’s not as though we see more of the war, in some ways the framing around it is worse, but in other cases, there is a lot of advocacy for people in other situations who are, we can say, victims of (U.S.) drone strikes and other forms of warfare. I’m thinking in particular of the Iraqis who really had nothing to do with 9/11 but somehow became the target of our ire. That goes back to the idea that there are people who we claim are threats to us and our homes, but actually, they aren’t. So there has been a lot of change and a lot of conversation on various, maybe not mainstream sites, but on social media about the experience of people in those other realms. Nevertheless, the dominant motivation for our support (of war) is nationalism and fear. Everybody fears that their own homes and their own families will be under threat. So the fact that the U.S. was attacked (in September 2001) made a lot of people feel that we needed to defend ourselves by any means necessary, even when it was actually an offense.

Turning to the home front, a lot of your work is concerned with investigating our assumptions about home and the house and what’s between those two in terms of expectations. Why do the home, housing, and especially the domestic interior appeal to you as a fertile ground for exploration?

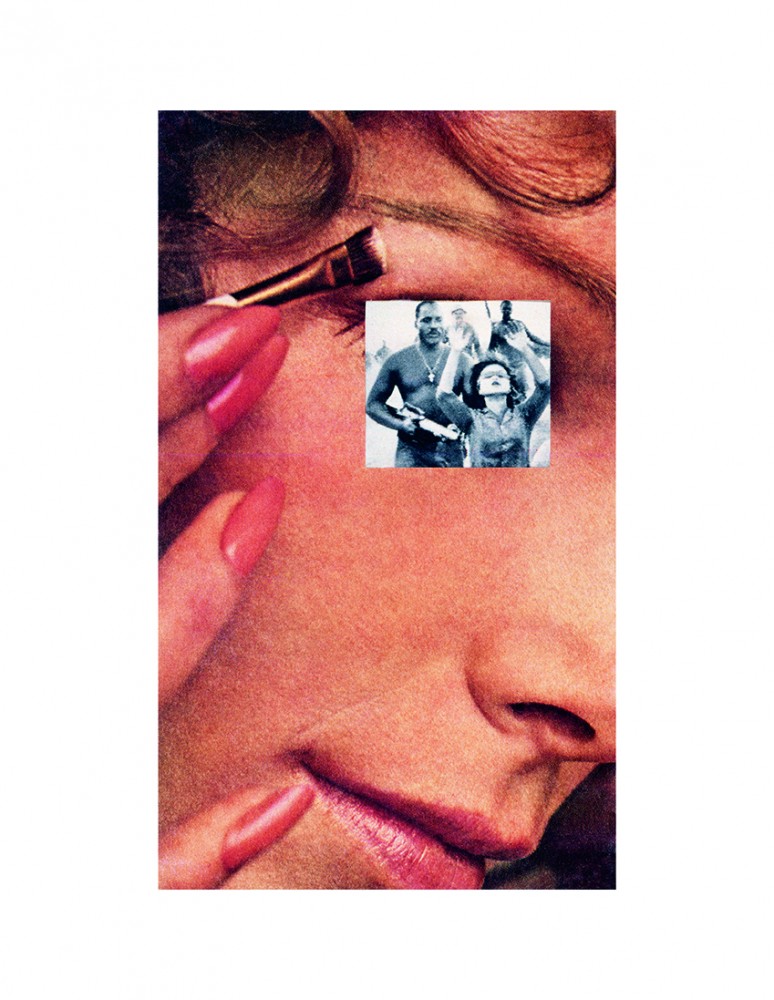

My first foray into that was actually as exteriorized as you can get. I was particularly irked and exercised by the images of women and women’s bodies in advertising in the 1960s and 70s that we saw every day or every week, whether it was in The New York Times or in various lifestyle magazines. I was really shocked at the way there was an easy slide from the image of the woman to the image of the woman’s surroundings. But it made sense because we have always assumed, even though it’s pretty much a Victorian idea, that women are responsible for the care and maintenance of the home and family.

Makeup/Hands Up, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, (c.1967–72); Photomontage. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

A Victorian idea, yet a remarkably enduring one.

Yes. And when I say “Victorian,” what I mean is the exclusivity of it was blessed as a viable idea in the Victorian age, if then, and by the time I was a teenager it was already being ridiculed. And yet it continues to have a powerful hold on us today. I will not contest the idea that women are responsible for reproduction and also the maintenance of the family and the home, and that we are nurturers. We are. But there was this idea that this was somehow melded into the home, the furniture, and all that other material, and there was a particular way that women were both seen as infants — because the 1960s especially were a highly infantilizing era for what women were supposed to look like — and at the same time had to be responsible for everything relating to kids and the home itself. So for me, it was an easy slide between the woman’s body and the woman’s home, and I think that actually there is some psychological resonance with that. Women really do identify with their homes — our homes, I should say.(Laughs.)

You graduated in 1965 from Brooklyn College and then spent time in California in the late 60s and 70s. Do you remember a particular moment when you first took notice of the misrepresentation of women in the media? Or is that something you already felt at a much younger age?

I was always surprised at the differentiation between what girls were supposed to do and what boys were supposed to do because I was pretty much a tomboy. But I didn’t realize until I was probably in late high school, I guess, and maybe even early college, that this was completely translated into these infantilizing images of women in advertising. Pop art generally tended to produce an image of a woman who was a pre-pubescent girl — and anorexic at that. It was completely acceptable and considered cute.

In 1975 you made Semiotics of the Kitchen, a 6-minute parody of a cooking show with you as a host. I still enjoy seeing how people react to it the first time they watch it.

Especially kids! Kids love it. (Laughs.)

SM: How did Semiotics in the Kitchen come about?

I had been doing a lot of thinking about and even writing about cooking, and the way that cooking transferred onto women the role of both producer and consumer of what formerly was haute cuisine. So, because we don’t have servants any more in the middle classes, women were supposed to be able to make something very special and also, of course, entertain and sit down and eat it with the guests. And I thought that was pretty crazy — and also pretty un-thought-through. (Laughs.) So I had written a couple of postcard novels about women in food, and I was writing a ridiculous extravaganza called The Art of Cooking, a fictional conversation between Julia Child and Craig Claiborne, who was the most influential food critic at the time because he was The New York Times (restaurant) reviewer. It actually just popped out of the drawer recently and I’ve been working on it again. This cooking culture was just something I was completely saturated in — questions of women and the kitchen and also the way it was portrayed on television. So one day I was walking down the street with my boyfriend, and let’s see, I was on Broadway approaching Astor Place. We had access to a video camera, and I thought that I would like to make this video using the alphabet. It just popped into my head, and we sort of did it on the spot.

-

Martha Rosler in her backyard in Brooklyn.

-

Martha Rosler in her backyard in Brooklyn.

What about your choice of aesthetic?

I was especially interested in the idea of a late-night local-TV look, where somebody just rents some time and then they sell you their Veg-O-Matic or something or other. And that’s what I did. We just filmed it at a friend’s loft. When we showed it for the first time, the reactions to it were very clear-cut. Most people, mostly men, hated it. They’d say, “This is not a serious artist.” I have that in writing! And I laughed when I read it because it was in Artforum, and I thought, “Here you are writing about me, and yet I’m not a serious artist!” And they didn’t understand what it could possibly be about, that’s what one curator said. And women loved it.

Zooming out from the domestic interior, how did you become interested in investigating public spaces and housing?

For a long time I wasn’t. I thought shelter was the most boring thing you could ever imagine. I used to think, “I’ve done work about food, I’ve done work about clothing, but I will never do anything about housing!”

-

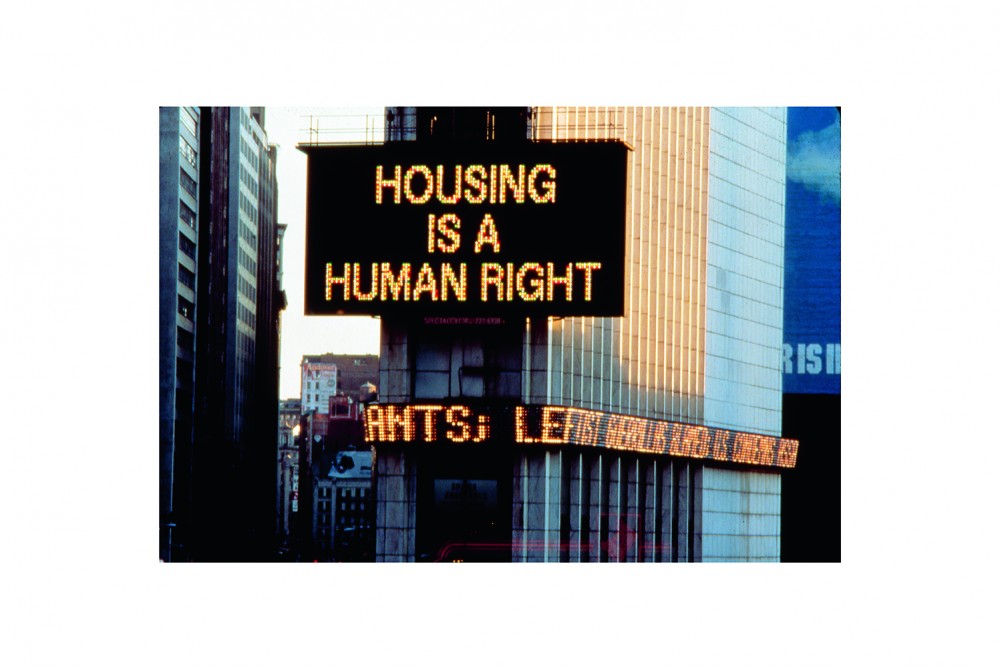

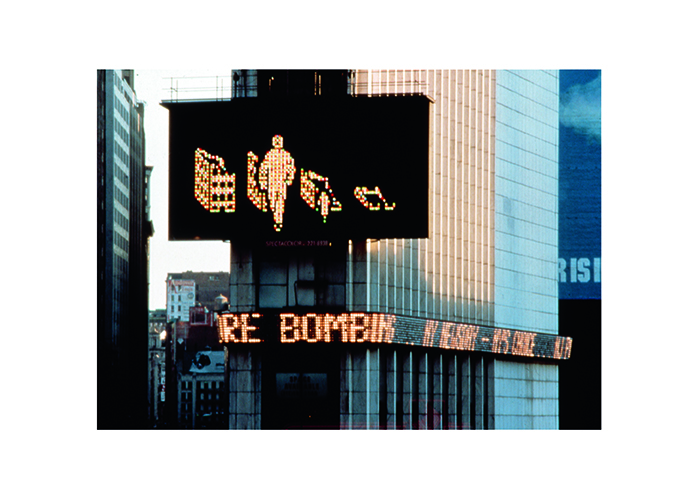

Photograph of Housing is a Human Right, (1989); Times Square Spectacolor animation, New York City. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

-

Photograph of Housing is a Human Right, (1989); Times Square Spectacolor animation, New York City. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Why do you think you originally rejected addressing the issue of shelter?

I think that in the 1970s women thought space was a male-artist issue, and process was feminine. And it took a while for it to penetrate with me, that space was also something that feminists should care deeply about. It sounds idiotic to say that nowadays, but you have to realize that the 1970s were a different universe.

And what made you change your mind?

I moved from San Diego to San Francisco and I heard about the crisis of affordable housing, and I learned about gentrification, and I started reading about it, and investigating it, and then I moved back to New York in 1980, and I thought, “Wow, people actually can’t afford to live in Manhattan anymore.” Like me! I had to move to Brooklyn! I’m from Brooklyn, so I thought it was awful. It’s a place to escape from. Or at least it was! I don’t still feel that way anymore today, obviously.

-

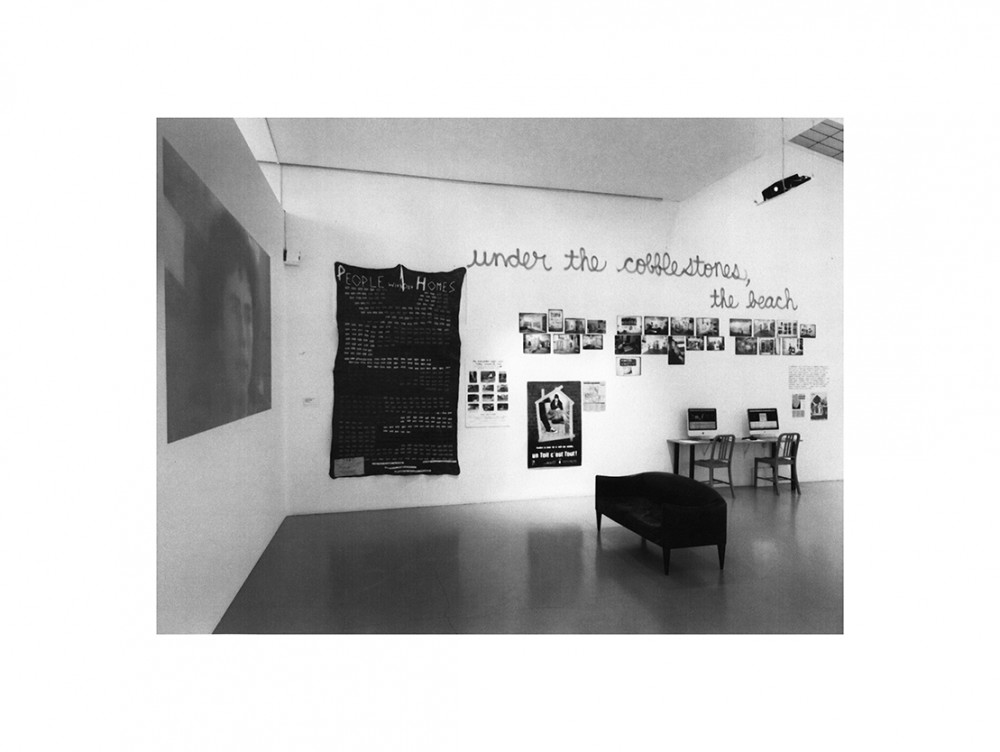

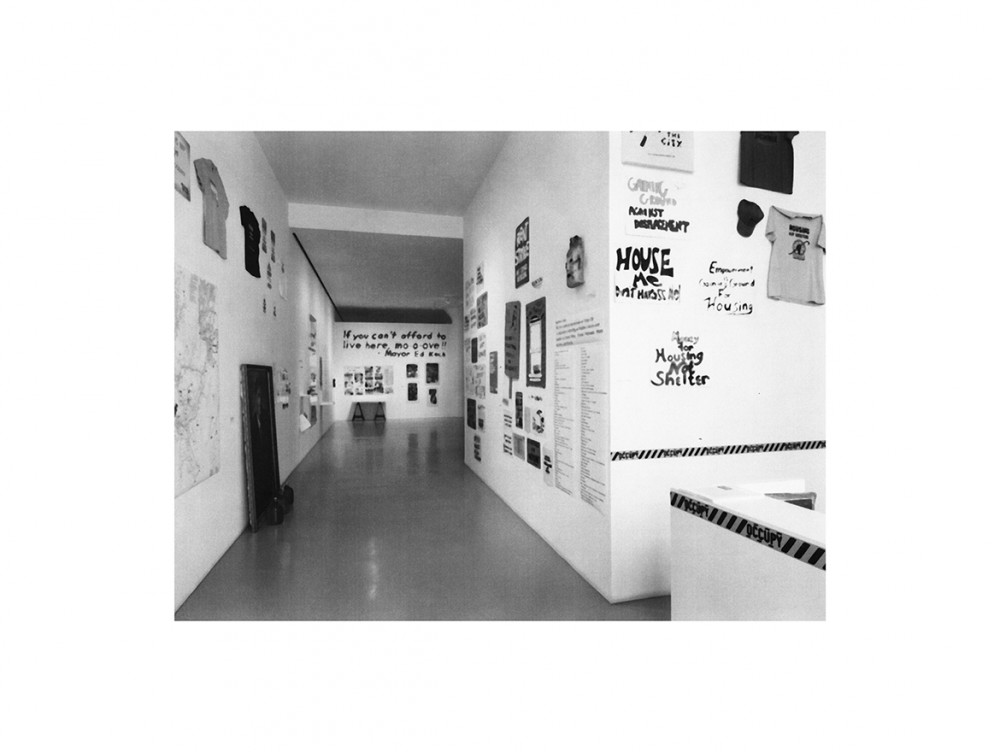

Installation view of If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ove!!, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York City, (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

-

Installation view of If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ove!!, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York City, (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

-

Installation view of If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ove!!, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York City, (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

And once you returned to New York, that’s when the exploration evolved into making actual work?

I didn’t actually make any work about it until the homelessness crisis in the late 1980s. We had never seen that before in New York. The idea that people could be sleeping on the streets and that they were considered not people for that reason completely horrified me. When I was given the opportunity to have a solo show at Dia (Art Foundation) in Manhattan, I said that I would love to do something about homelessness. They were a little bit leery, but I managed to do that, and to realize that so many people have so much to say about it in the art world that what I should do is collect people’s responses and curate a show, and that’s what I did at Dia (in the 1989 exhibition If You Lived Here...). I also started writing about it, and I published two books about it — about housing and access and gentrification and its relationship to art, because artists are both the gentrifiers and they are the ones who are being gentrified out.

Photography didn’t really start to play an important role in your work until the 1980s. Why is that?

That’s exactly the time when I was dealing with these issues such as housing and gentrification in relationship to the political, financial, and art systems of New York City. I decided I needed to pay more photographic, or you might want to say documentary, attention to the spaces we inhabit, and, more importantly, to those we pass through. Those spaces that define, in some sense, the public, but also transportation, which is essential to communication and to life in general. That’s when I spent a couple of decades using my camera, and of course still do to this day.

The Gray Drape, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series (2008); Photomontage. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

One of your more recent photographic series is Off the Shelf: War and Empire (2008–18). Can you tell me a little bit about these photographs?

If you don’t look closely, they look like piles of books, arranged fairly straightforwardly, but they are actually digital images of free-floating spines, and there is no book behind the spine. It’s based on a traveling library I had for a while, which was really a reading room with about 7,500 books. It was primarily in New York but also went to a number of cities in Europe, and was even supposed to go to Asia. But I had to call a halt to it at a certain point, because the books got very tired and wanted to go back home. In the end, I was not that happy that it was interpreted partly as a portrait of me, because it was intended primarily as a vital resource for artists. We need to remember that there is a lot of information and knowledge and wonderful stuff out there, mostly non-fiction but fiction as well — the library was mostly non-fiction — that we need to draw upon in order to remain invested in our world as everything goes online, and it appears as though everything is present, but in a way that means nothing is present and we don’t know how to pay attention to serious arguments. The library was intended as something that would say to younger artists, “Please remember to engage with millennia of knowledge,” and also, “Look how beautiful books are!”

Do you consider Off the Shelf another kind of floating library?

I really don’t know how to describe it. It was a way of pointing at it without saying, “This is a heavy reading list,” because those works are not reading lists, they are suggestions of where a reader might want to go if they want to know about art, activism, and education; or about urban space; or about the history of occupation in the public sphere, like Occupy, which I was a participant in, but also the Paris Commune and other forms of occupation.

Martha Rosler in her livingroom.

Would you say that living in the age of Trump has affected you in your artistic practice?

It’s affected us all. I also made a work about Trump. It’s called POINT AND SHOOT, a mourning thought (though I am more enraged than in mourning), (2016), and it’s another kind of photomontage — it’s part of the exhibition at the Jewish Museum. And I’m in the process of editing a video about Mike Pence. And of course I have spoken about this publicly, reminding artists that we can do things that make a difference. I was part of a group of artists against the war in Iraq. And then Obama was elected, at which point we all sat back down, which is a little bit sad but totally understandable. So in a sense my aim now is to rally the forces again, and say, “Come on! Get out there and do all the things we can do — performances and theater and protests and postering and constantly being visible in the world.” The only thing I don’t want to do anymore is be a graphic artist and design the posters. (Laughs.) There are many people out there who are much better at it than I am.