BOOK CLUB: Snarkitecture, Architecture’s Excavation Artists

Snarkitecture creates places and spaces, furniture and objects, but the practice is perhaps best known for what it doesn’t do. The New York-based studio — co-founded in 2008 by artist Daniel Arsham and architect Alex Mustonen, who were joined by architect Benjamin Porto in 2014 — has carved out a bright, white, shape-shifting niche with projects that are neither art nor architecture: a flotilla of inflated cylinders forming a welcome pavilion, a mass of architectural foam dug out to create a cave, a fashion show invigorated by a thicket of blanched confetti, a cement “pillow” permanently imprinted with the profile of an iPhone. And so antipodes — rather than chronology or typology — are the organizing principle for Snarkitecture’s eponymous first monograph, recently published by Phaidon.

Pillow (2013), with folds cast from white gypsum cement, provides a dedicated resting place for your keys or phone. Keychain by Various Keychains

“As we were trying to figure out how to tell the story of the last ten years, patterns emerged,” says Mustonen. “With the book, the largest thing we resolved was this idea of the format, of placing our projects within a range that goes from ‘not art’ to ‘not architecture.’ These things are kind of both and neither at the same time.” If that sounds like the “jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, but never jam today” conundrum championed by Through the Looking Glass’s White Queen, it is, of course, by design. Snarkitecture took its name from another Lewis Carroll fever dream, The Hunting of the Snark, an 1876 poem that can be summarized as the impossible journey of an improbable crew to find an inconceivable creature. “Their ocean chart is a blank white piece of paper,” says Arsham. “So for us, there was a link between trying to find something that is undefinable and using limited resources to achieve that.”

Installation view of Fun House (2018), Snarkitecture’s anniversary exhibition at the National Building Museum, Washington D.C., curated by Maria Cristina Didero. Photograph by Noah Kalina.

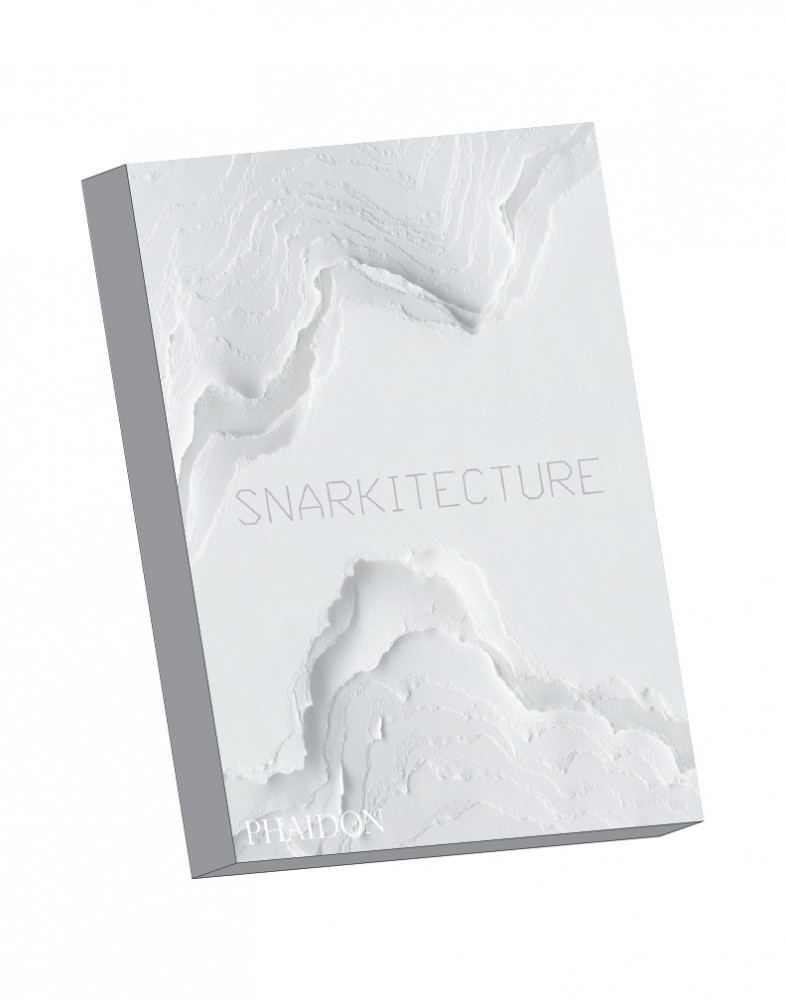

Making — the physical realization of ideas — has always been at the heart of Snarkitecture (at their Long Island City studio, one enters through the workshop), and the practice has developed a knack for transforming familiar materials into beguiling and memorable experiences on scales ranging from the intimate — Beats headphones in ghostly white enshrined in their own cultured-marble pillow — to the immersive — 10-foot-tall climbable concrete letters that evoke the memory of Miami’s demolished Orange Bowl Stadium. The 256-page monograph documents a remarkable range of 73 projects, complete with an alphabetically ordered “technical index” of diagrams, stats, and specs for each one. Examining Snarkitecture’s work to date clarifies the practice’s defining talents: as expert calibrators of multiplicity and restraint, they are constantly seeking new ways to balance seriality with subtraction — to dazzling effects. In July 2015, Snarkitecture filled the soaring atrium of the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., with an ocean of nearly a million plastic balls to create The Beach, where more than 160,000 visitors frolicked in the all-white “sea.” And through the seven stores they’ve created for Ronnie Feig’s streetwear brand Kith, the studio has emerged at the forefront of contemporary retail design. Kith’s Los Angeles emporium, which debuted in February 2018 on a steeply pitched corner of Sunset and La Cienega, leaves half of the store below grade, a subterranean opportunity snatched by Snarkitecture, who set the illuminated glass façade inside the garage and behind a perforated concrete wall (excavation, the peeling back of layers, is a recurring theme for the practice, as evidenced by the book’s glacially craggy, laminar cover photo). Now that Snarkitecture opened Fun House, an exhibition curated by Maria Cristina Didero about their ten years of work staged at the National Building Museum in Washington D.C., Arsham thinks back about the Snarkitecture’s beginnings: “We always thought our work was going to be about collaboration with architects, working inside existing structures. But the practice has actually gone in a direction that’s more about the creation of unique spaces.”

Text by Stephanie Murg.

Taken from PIN–UP 24, Spring Summer 2018.

Snarkitecture, by Snarkitecture (Phaidon, 2018).