CONCRETE POETRY: REVIVING EDWARD JAMES’S SURREALIST MEXICAN ESCAPE

Nestled between mountains deep in the dark, lush heart of Mexico’s Huasteca Potosina region lies the tiny town of Xilitla. Meaning “the place of snails” in the ancient Aztec Nahuatl language, Xilitla is the entryway to Las Pozas. A winding, man-made reverie of a landscape, Las Pozas lies 2,000 feet above sea level and covers 80 acres of rainforest, waterfalls, and natural freshwater pools (pozas means “pools” in Spanish) to which reinforced-concrete bamboo shoots, petrified cascades, massive petaled columns, and Piranesian staircases have been added at every turn. The history of this concrete fantasy garden turned cult destination can be traced back to the late 1940s, when the eccentric British millionaire, Surrealist art patron, and avid bisexual Edward James left his family’s 300-room stately home in Sussex first for Taos, California, and later for Cuernavaca, Mexico, before settling in the Huasteca region. In search of his own personal Eden, James had originally fancied farming rare orchids on the site, but in the early 1960s, after a freak frost destroyed most of the flowers, he opted for a less fragile form of beauty. At times employing as many as 100 workers, James spent the next 20 years, until his death in 1984, transforming this remote jungle location (the nearest airport is over three hours’ drive away) into a Surrealist concrete folly, funding the construction by selling off part of his vast collection of paintings, which included Carringtons, Dalís, and Magrittes.

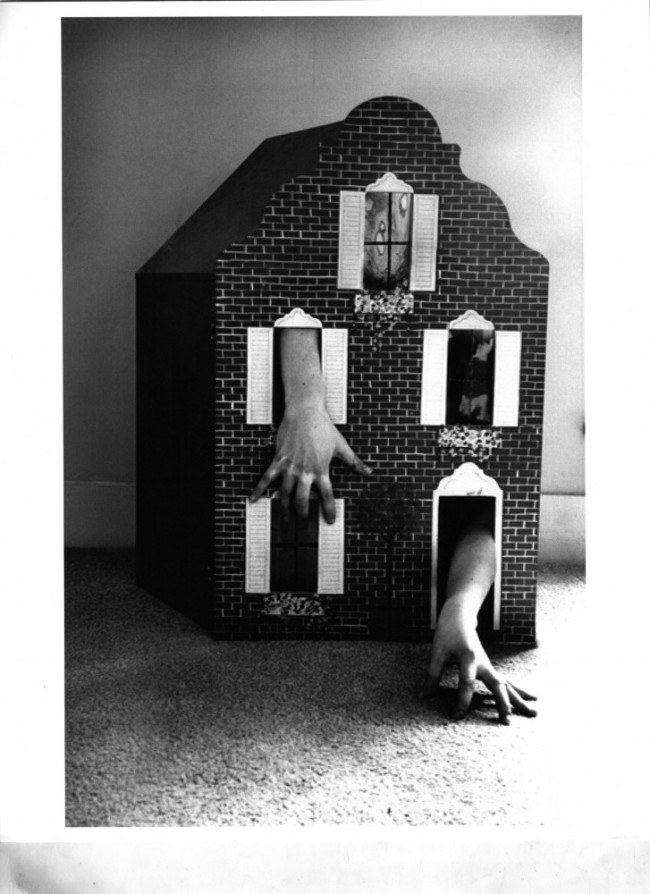

Since 2014, architects Umberto Bellardi Ricci, Carlos H. Matos, and Kanto Iwamura have been leading an experimental concrete summer workshop in Las Pozas with support from London’s Architectural Association. By reviving James’s carpentry workshop and locally sourcing raw materials such as wax, clay, gravel, wood, and natural dyes, they perform a sort of reverse archeology, designing modular sets and fragments of would-be ruins. Together with a team of construction enthusiasts, both local and international, they set up shop — surrounded by exotic birds, multicolored centipedes, anteaters, and armadillos — to experiment with formwork, casting techniques, and organic aggregates. Not only are they mirroring James’s own exercises in the production of concrete structures in a remote location under challenging climatic and technical conditions, they are also investigating a tradition of monumental, geometric abstractionism and a fascination with pre-Hispanic aesthetics that has framed Mexican Modernist architecture for almost a century.

Text by Mario Ballesteros. Photography by Lucas Cantú.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 20, Spring Summer 2016