MANCHEGO MODERN: The Peculiar Architecture of Miguel Fisac

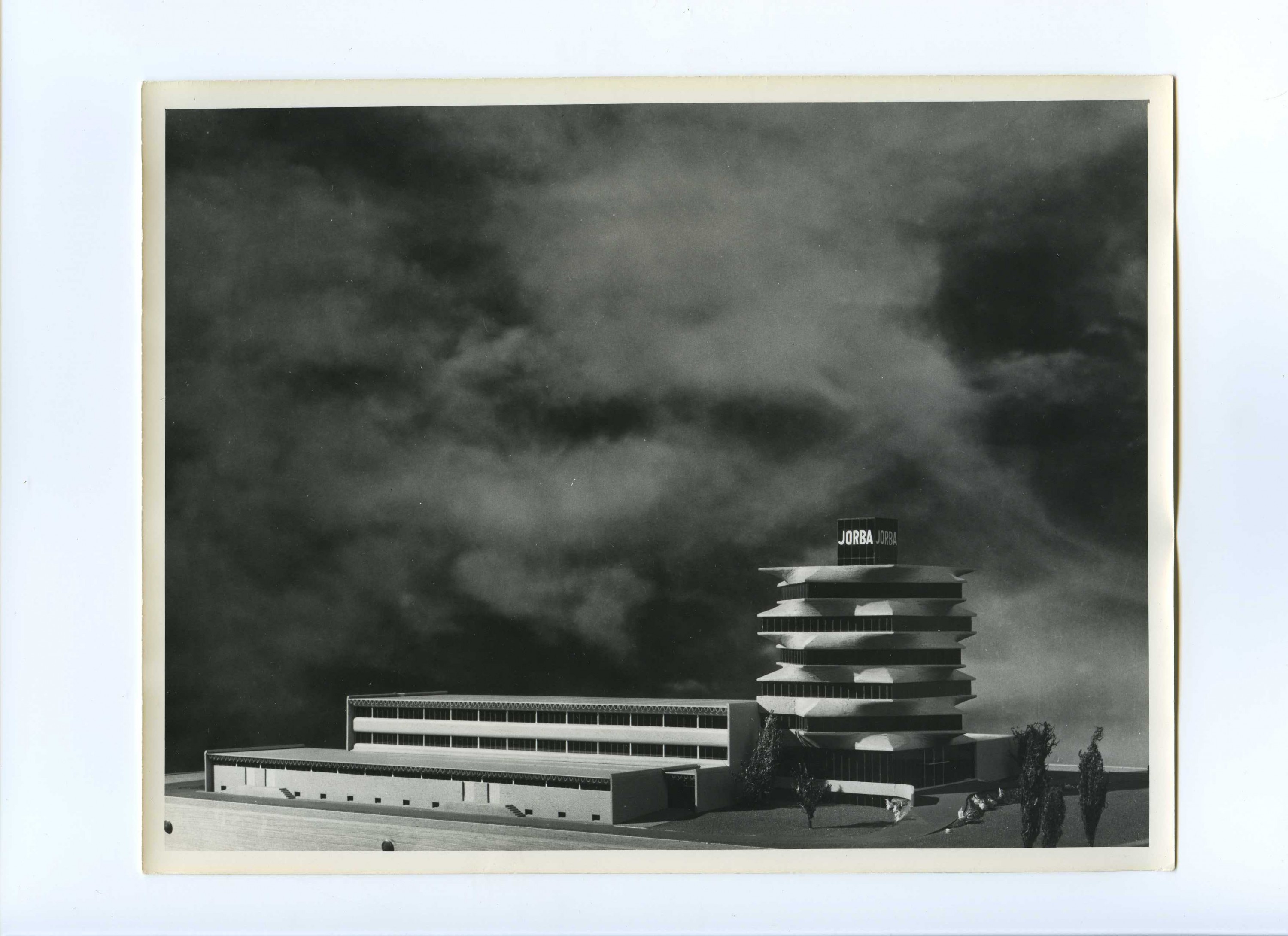

Built in 1965–67 on the outskirts of Madrid, Miguel Fisac’s Laboratorios Jorba was one of the most formally daring structures of the Franco dictatorship. It was nicknamed the “Pagoda” for its peculiar tower: a stack of five square-plan stories with every other floor rotated 45 degrees, creating a corkscrew of hyperbolic paraboloids crowned by eight concrete spires, giving it an exotic, far-eastern feel. Shortly after its demolition in 1999, the then 86-year-old Fisac shrugged off a question from Spanish daily El País regarding his lack of work, despite his having enjoyed a fruitful career spanning over three decades and 400-plus built works: “I guess my architecture has been kind of hortera, They only want luxury condos nowadays.”

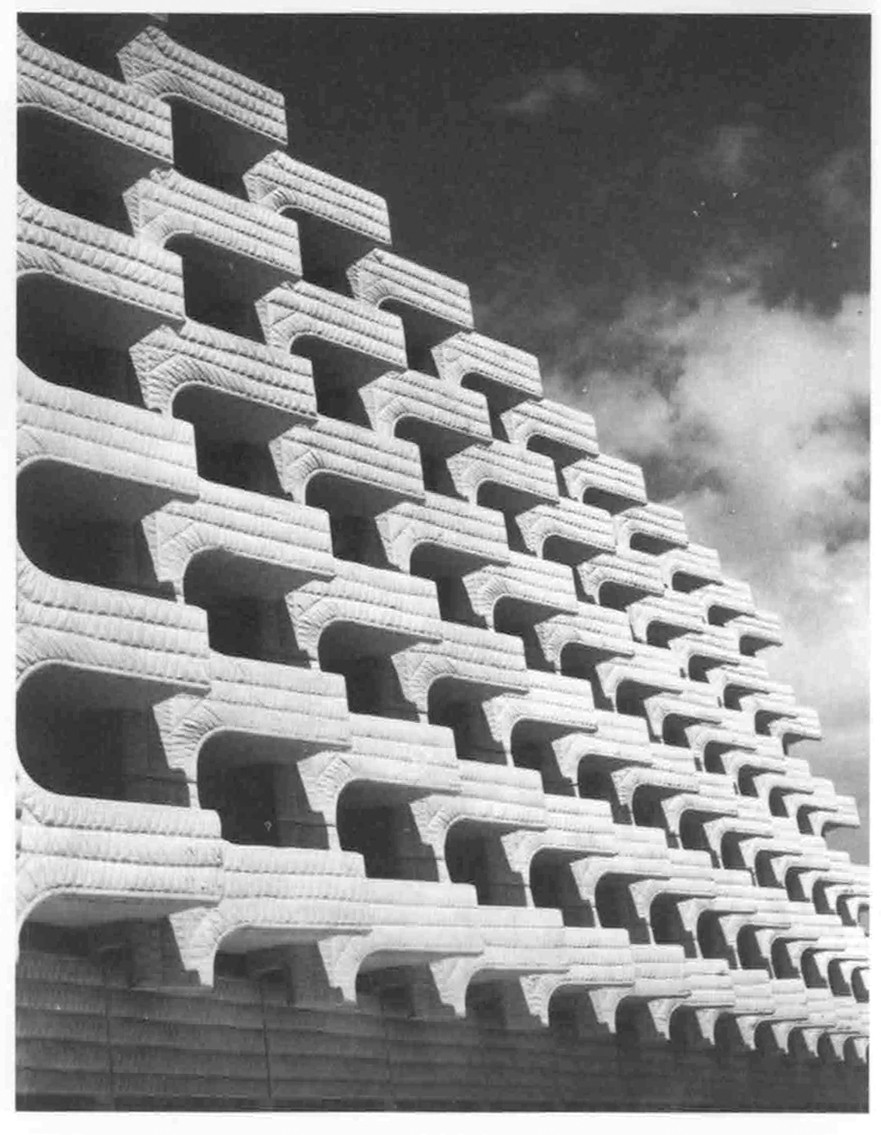

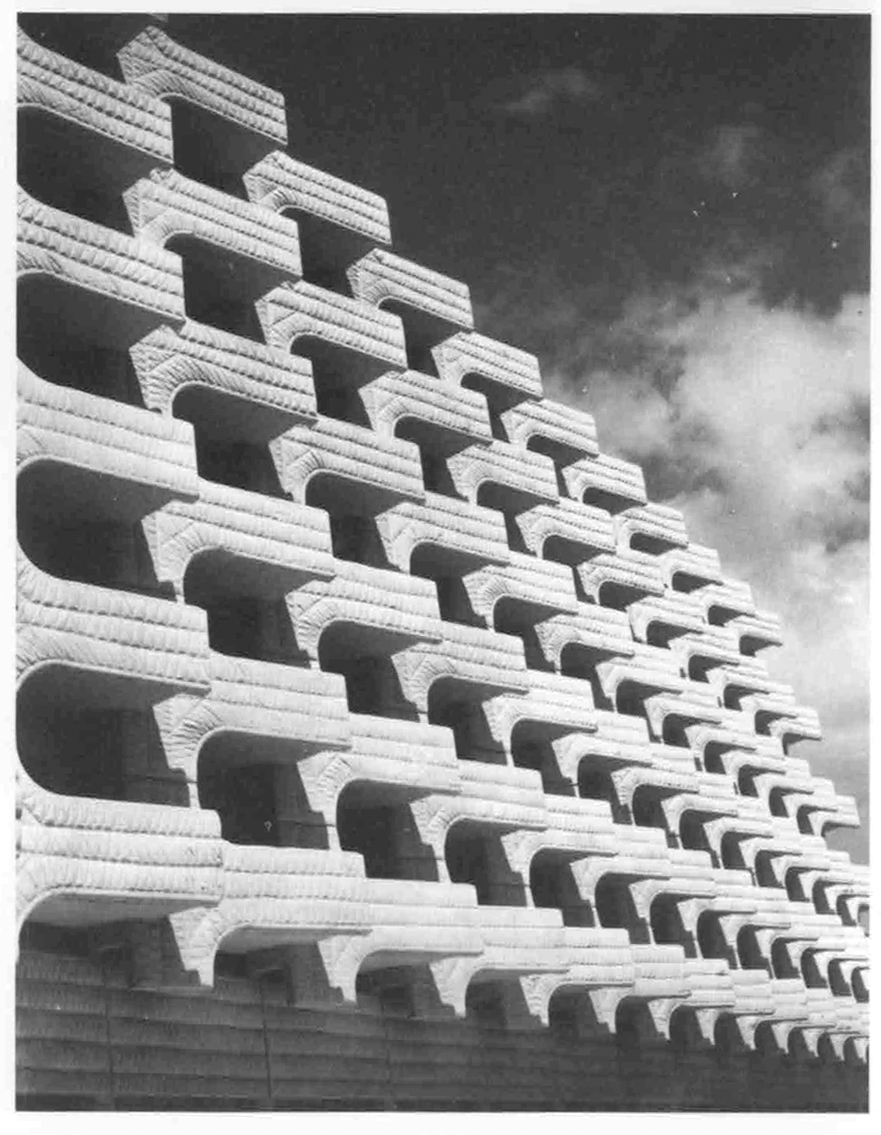

Hotel Tres Islas (1973–75), in Fuerteventura, Spain. © Fundación Miguel Fisac

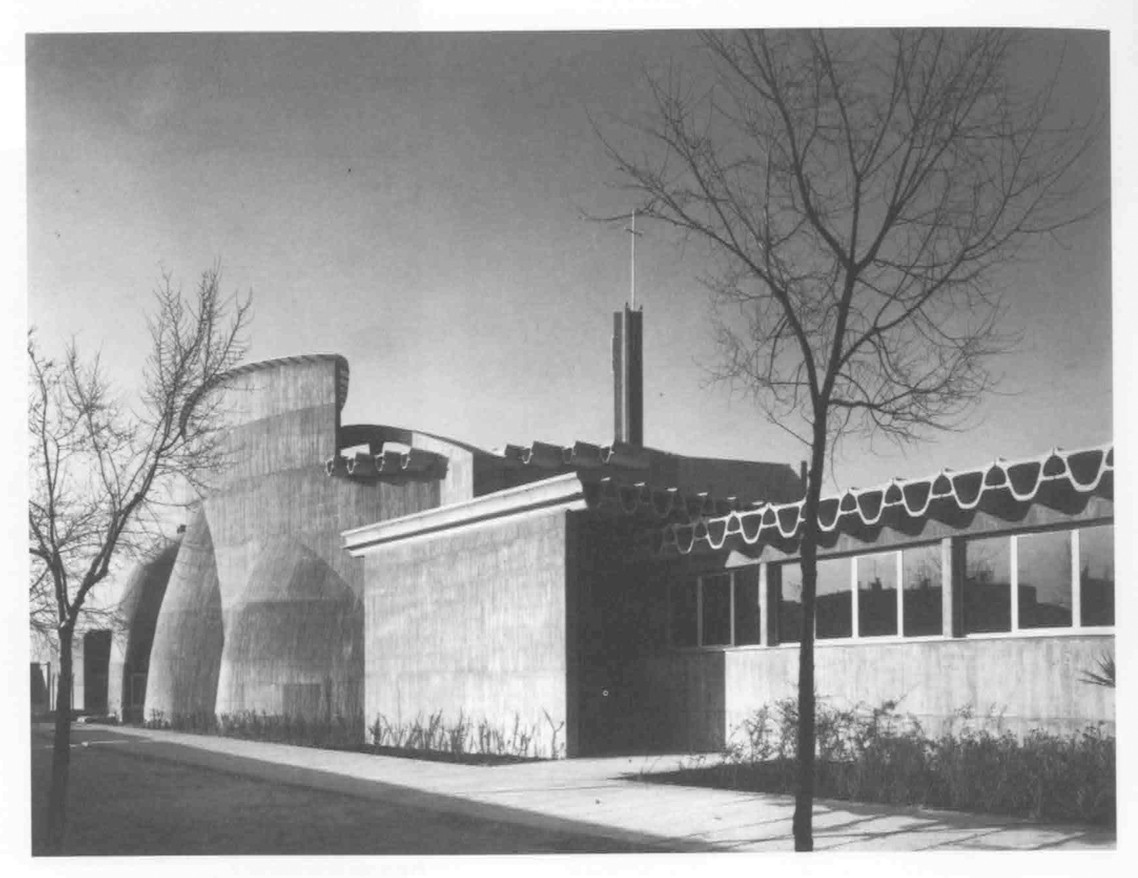

Why would a man as serious, sensible, and polished as Fisac ever consider his work even the slightest bit hortera? (a word that roughly translates as “tacky,” and which found its way from the literature of 19th-century costumbrismo to become a key cultural signifier in post-transition Spain: touching on exaggeration, crudeness, and questionable taste, lo hortera tangentially relates to kitsch and camp). Born in 1913 in the tiny Manchego town of Daimiel, Fisac was forced to leave his architecture studies in Madrid at the outbreak of the Civil War. A devout Catholic, he sided with Franco and even became an early member of the cult-like Opus Dei. His wartime allegiances landed him his first commissions after graduating in 1942 and, despite his strong, independent disposition — he liked to think of himself as the regime’s architectural bête noire — clearly defined his early work. Fisac’s first project was a chapel for the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), which was built over the war-destroyed remains of a Modernist auditorium by Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez — part of a research cluster that had been a hive of intellectual and political activity during the 1930s before being taken over by Opus Dei after the conflict. Fisac wanted to respect his predecessors’ clean rationality despite the programmatic and symbolic overturn, but nonetheless couldn’t help but dress the structure with the historicist, Classicizing embellishment expected in state-commissioned works.

Miguel Fisac surrounded by prefabricated elements used during construction of the Center for Hydrographic Studies (1962). The Spanish architect developed many prefabricated, prestressed concrete beams inspired by the structure of bones and featured them prominently as design elements in many of his projects. © Fundación Miguel Fisac

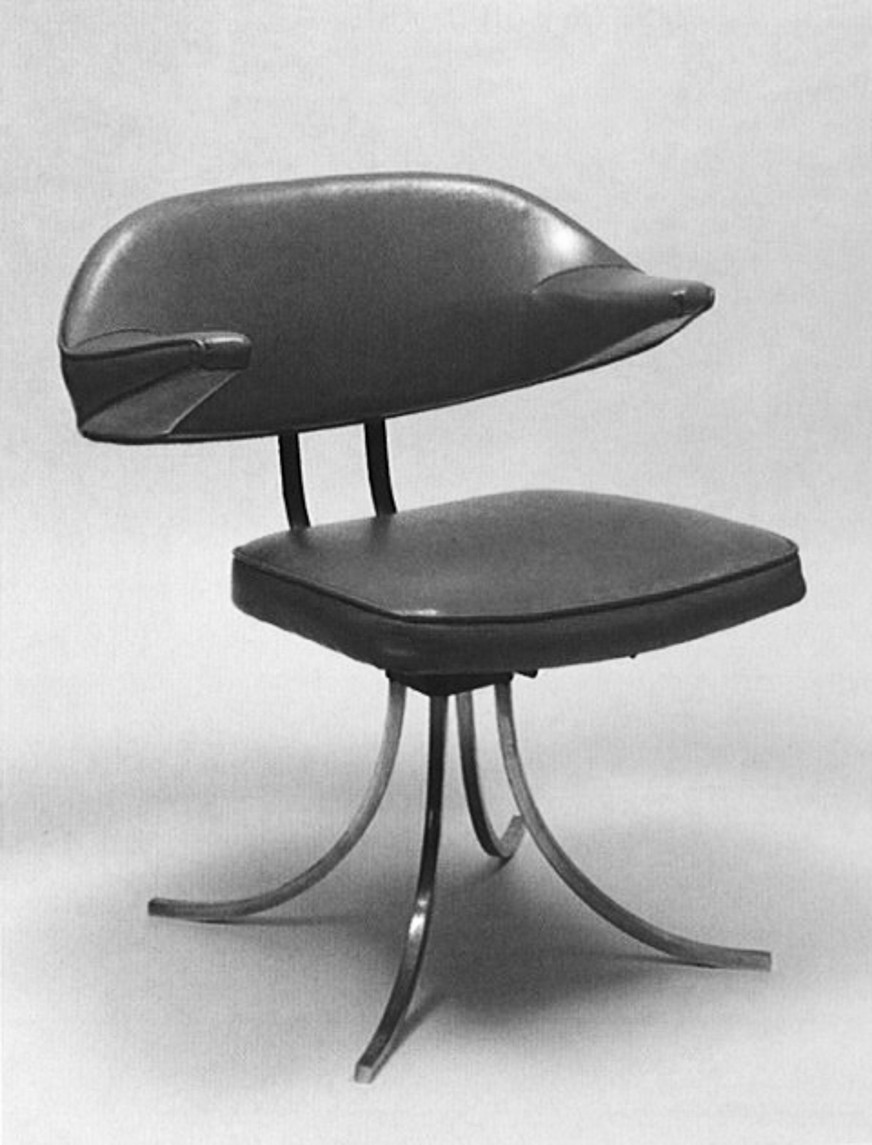

As he gained recognition and experience, Fisac managed to become more independent, even while working for the regime. The modest Instituto Laboral (1951–53) in Daimiel, with its combination of traditional Manchego building techniques and striking Nordic-inspired modern interiors, signals a clear shift from his earlier projects. In the mid-1950s, Fisac left Opus Dei, got married, and traveled to Japan, Israel, and the U.S. This period of personal and spiritual reckoning further intensified his unique design vision. In the late 1950s and early 60s, he began a “purer,” more serious form of experimentation, eschewing stylistic considerations and focusing on design procedures and techniques: housing prototypes, prefabrication systems, assembly processes, pre-stressed-concrete testing, and the development of construction patents. Still, there is a hint of humor and irony in the primitive and symbolic connotations of his huesos (bones) — large-scale, hollow, pre-stressed concrete girders initially developed for the Instituto de Estudios Hidrográficos (1960) that played with formal references to skeletal structures. And there are winks of hortera in his sleek yet sleazy Toro armchairs (1950 onwards), whose combined back/armrest is shaped like a bull’s head.

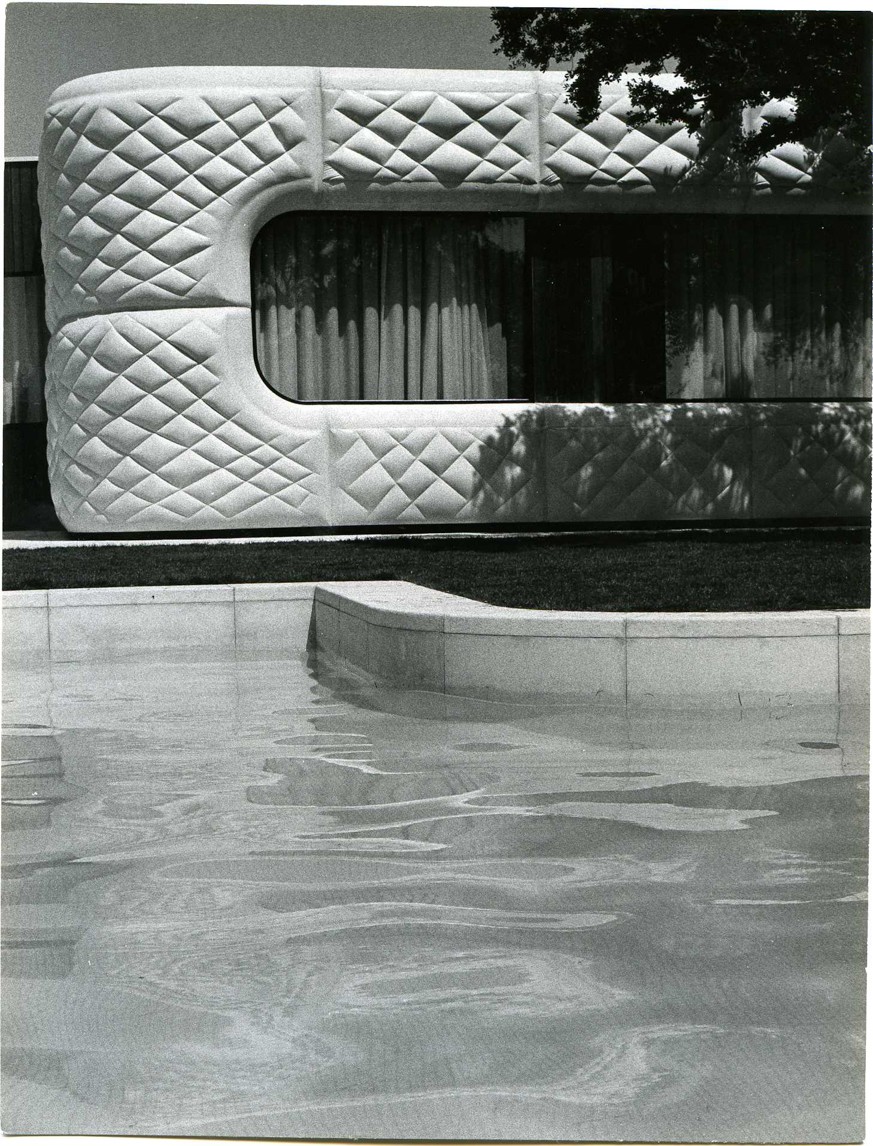

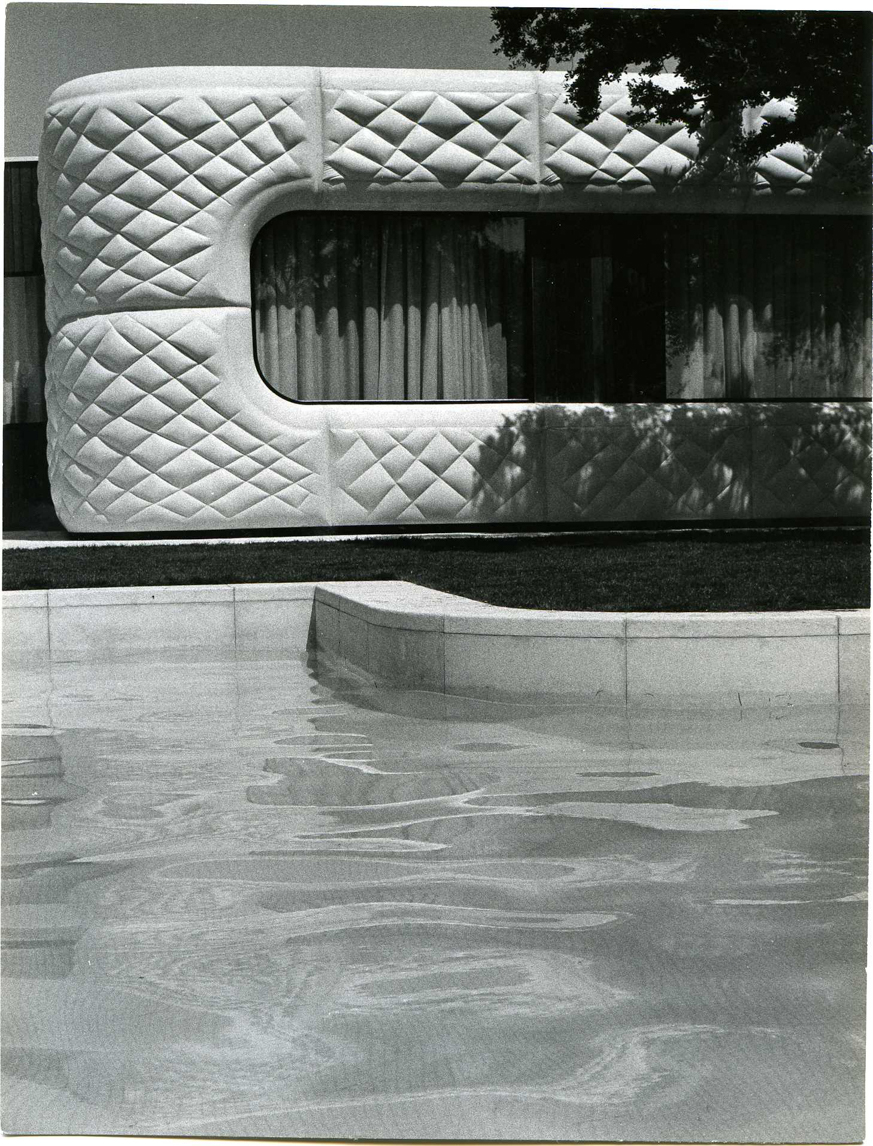

View of La Moraleja House (1973), in Madrid, Spain. © Fundación Miguel Fisac

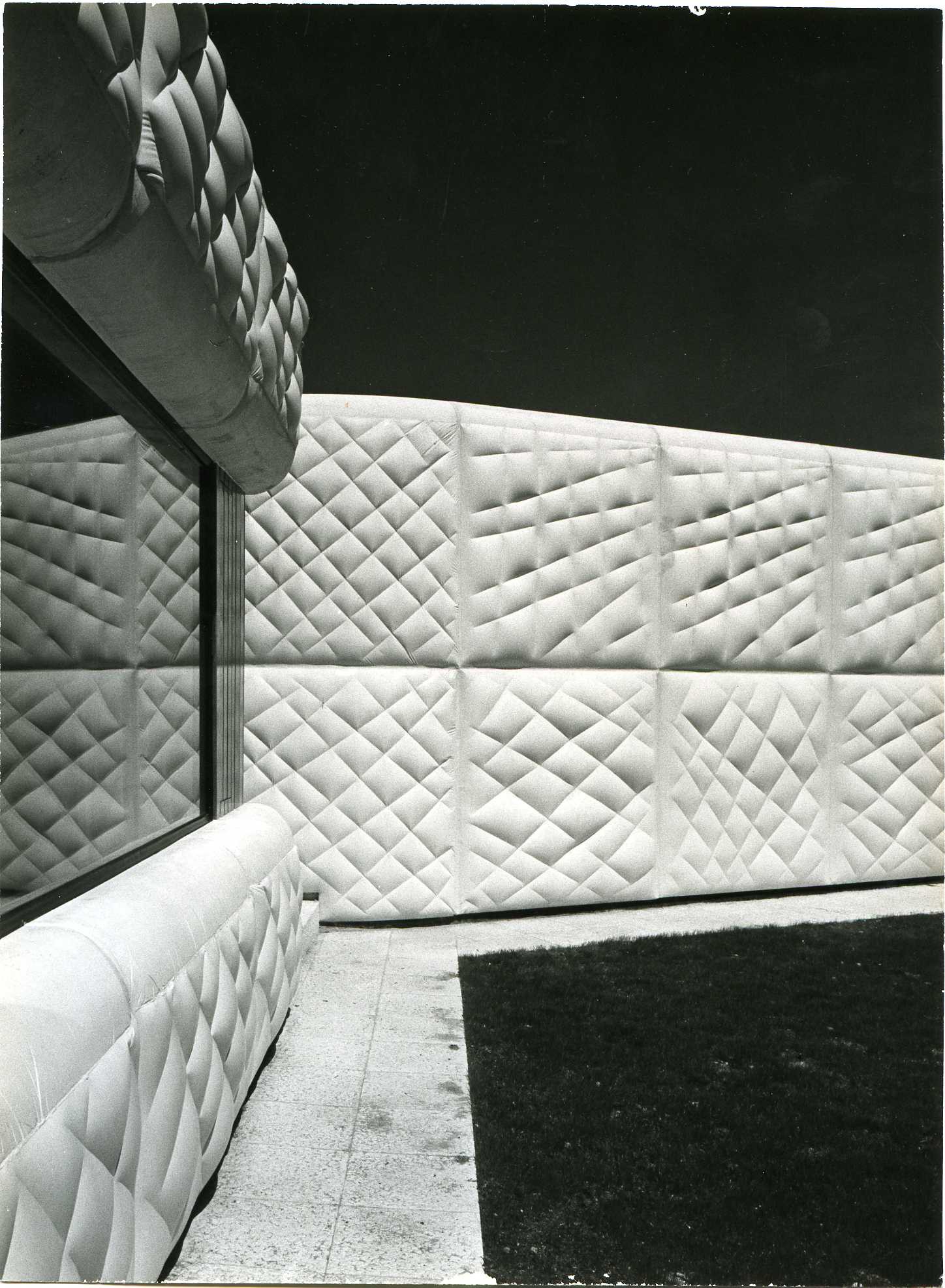

But the true hortera in Fisac came out in the late 60s and early 1970s, when he undertook a series of precocious experiments with flexible formwork, which he improvised out of wire frames and plastic sheeting. He first used this method, which captures the fluidity of poured concrete in textured, spongy surfaces, in the MUPAG rehabilitation center in Madrid (1969), and later adopted it for what might be his most hortera building of all, a house in La Moraleja (1973–75). Located near Madrid’s Barajas Airport, this home for an engineer and his family is a Pop-age country cottage, resembling an inflatable that has landed in a bizarrely pastoral landscape dominated by woodland and heavy air traffic. The white-concrete façade appears plump and cushiony, as though you could bounce off it, the padded effect being intended to “leave some trace of (its) having been soft.” Custom-fitted neoprene window profiles keep out airplane noise, while external oak paneling and ventilation louvers soften the divide between house and landscape. It’s a melodramatic structure, playful yet defensive, turning itself over to both the stoic romance of the peasantry and the discreet leisured charms of the middle class, all the while flipping the bird at the ugly urbanization of Madrid’s periphery.

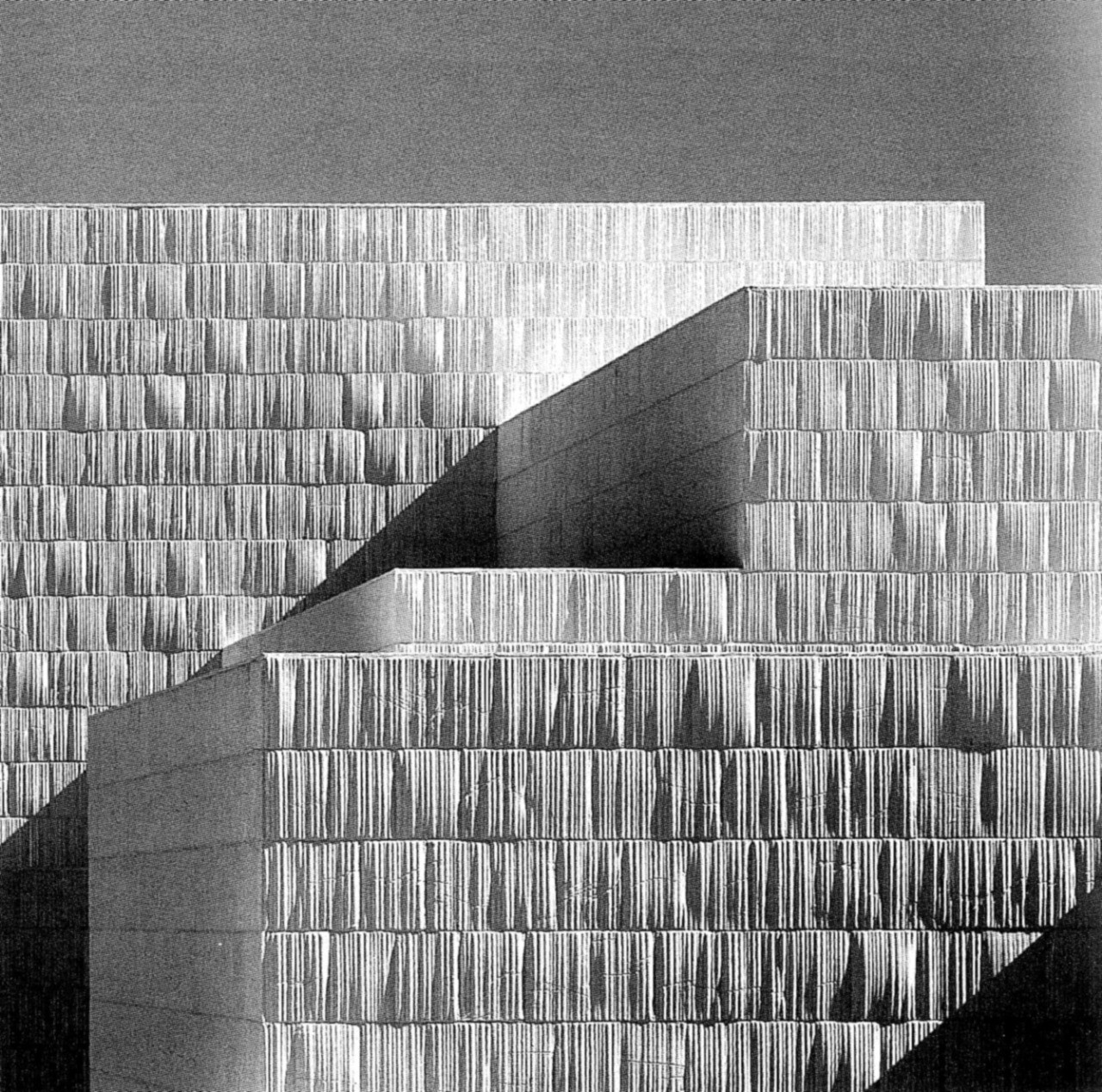

IBM Office Building (19966–67), in Madrid, Spain. © Fundación Miguel Fisac

Fisac’s architecture is hortera not because it is crude or obvious or over-the-top (though it may be at times), but because it managed to turn the trite and aspirational frippery of Francoist Spain into a unique adaptation of Modernism characterized by touches of traditional regionalism, technical innovation, and a slightly subversive humor. Lo hortera, to quote Susan Sontag’s Notes on Camp, “doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is to offer a different — a supplementary — set of standards… (it is) the sensibility of failed seriousness.” And just like camp, the point of lo hortera is to “dethrone the serious.” Fisac’s witty architecture sheds light on Spain’s rough transition to modernity — good, bad, and ugly — and is at once both a product of and a resistance to this transition. Playing within but gnawing at the limits, it pushed for change even when the times weren’t quite ready for it.

Text by Mario Ballesteros. Taken from PIN–UP 18, Spring Summer 2015.