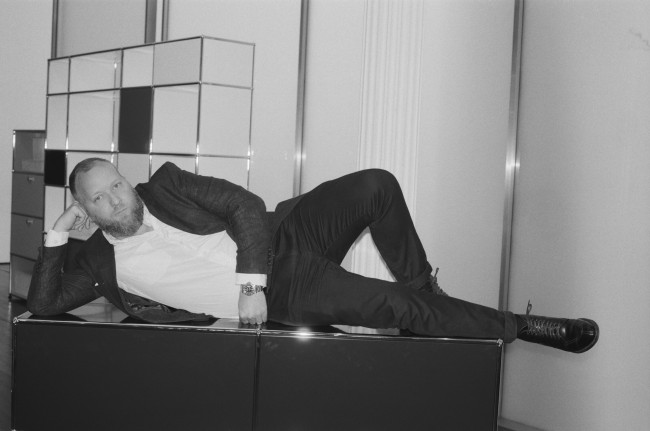

DADA ISSUES: INTERVIEW WITH ARTIST ADAM PENDLETON

Encompassing painting, performance, video, and archival documentation, conceptual artist Adam Pendleton’s practice spans disciplines, hinges on experimental use of language, and employs historical references and re-appropriated imagery to sly and subtle effect. At this summer’s Venice Biennale, the Virginia native’s work was showcased at the Belgian Pavilion. PIN–UP caught up with the 32-year-old artist back in April, a few weeks before the opening of the pavilion (which closes this upcoming weekend), to talk about his concept of Black Dada and the manipulation of space.

Your work will be shown in the Belgian Pavilion at the upcoming Venice Biennale, as part of a show which is being billed as an exploration of “the history and afterlife of colonial modernity.” What does that mean?

The idea is to explore Belgium’s colonial past through a group exhibition. The artist Vincent Meessen’s work will function as an anchor, and also as a lens through which to view other people’s work, including my own. There’s also a larger concept at work, namely: what does Belgium’s colonial past represent within the context of the Biennale and the pavilion itself? The Belgian Pavilion, it turns out, was the first foreign pavilion to be built in the Giardini, under the reign of King Leopold II, who is of course known for creating his personal Congo Free State. The organizers, Meessen along with curator Katerina Gregos, chose artists whose work examines or deconstructs, one way or another, colonialism or decolonization.

Do you or your work have any direct connection to Belgium or colonialism?

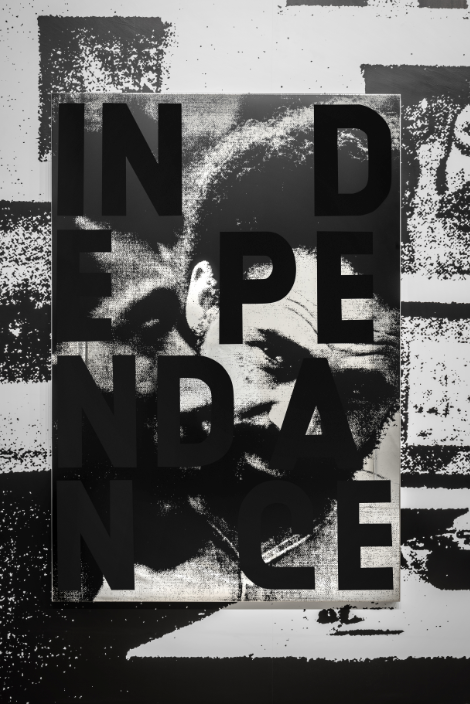

I’ve been working on a project that looks at the independence of the Congo, but through a kind of multi-faceted and at times oblique method. Quite simply, I think the organizers were drawn to the idea of “Black Dada” which I’ve explored in my work, and in examining the influence of Africa on Europe and of Europe on Africa.

What is Black Dada?

Originally I came across the expression in an Amiri Baraka poem entitled Black Dada Nihilismus, and it has since informed a number of my works, spanning from paintings to an ongoing, ever-shifting archive which I document in the Black Dada Reader. There, something enters and becomes archived and then, rather than letting it go, I’m perpetually looking for its poetic potential or its symbolic potential by asking it to function in many different contexts. Black Dada is a way for me to talk about the future of the past.

Are you creating new work with the Belgian Pavilion in mind?

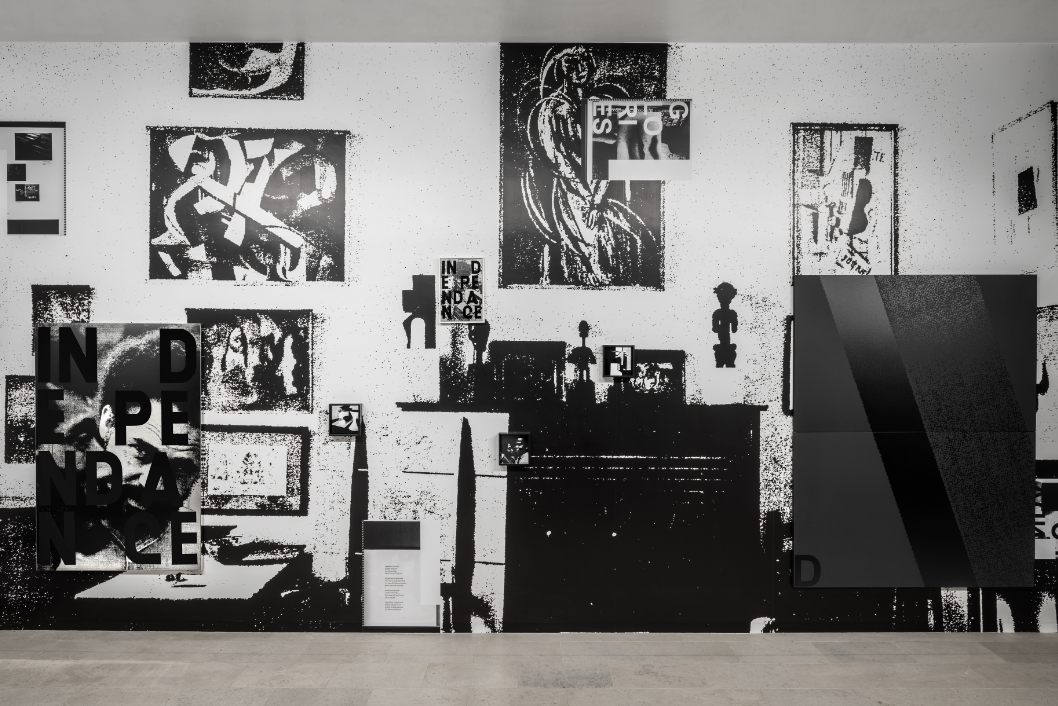

I’m creating new ways of viewing existing work particular to the setting at hand, along with some new pieces — but the new pieces are continuations of ongoing projects. I tend to start a project and work on it for a long period of time. The Black Dada paintings that will be displayed in the pavilion, for example, are part of a project that began around 2009 and has shifted and changed conceptually, as well as in terms of content and aesthetic approach. The Belgian Pavilion is a large central space around which there’ll be a series of individual projects presented in small or medium-sized satellite galleries — they’re kind of like a series of solo projects.

Do you think that particular arrangement of space will have an impact on the way your work is perceived or interpreted?

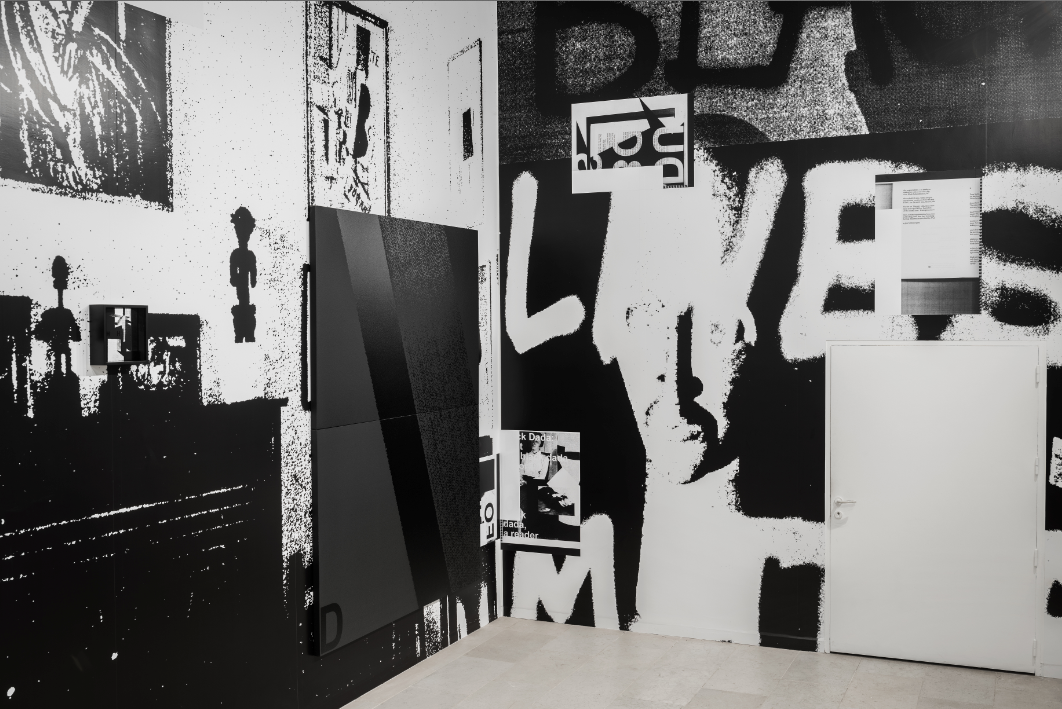

I always ask myself, “How does Black Dada function?” I think the pavilion offers a unique lens, spatially, through which to frame that question. I’ll be installing on a very large wall, and I’m going to wallpaper it with a very large reproduction of the Arsenberg apartment in New York as it was photographed in 1918 (the home of art collectors Walter Conrad and Louise Arsenberg). Their home was filled with art and objets from Africa as well as pieces in the Dadaist tradition. Their apartment was a kind of salon in which a diverse group of artists from the early 20th century would meet and converse. So I’m kind of recreating that space and hanging my work on top of it — I’m creating and shaping an environment without physically changing the space.

Have you ever collaborated with an architect directly?

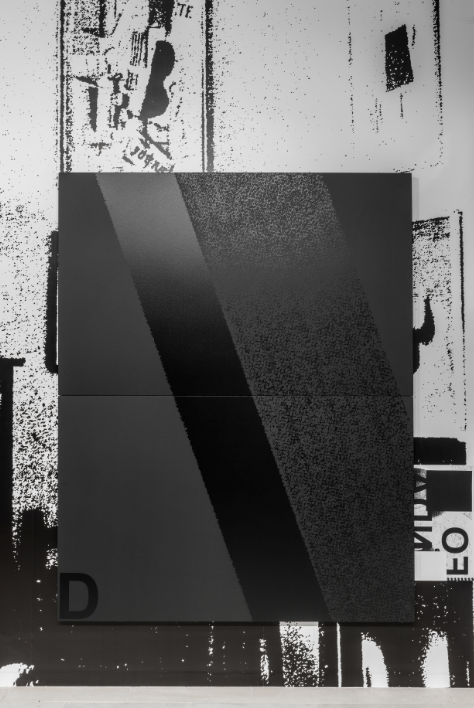

I’d love to work with an architect to create an environment specific to my work. I use a lot of mirrored surfaces, and I’m very interested in how people like Joan Jonas, Robert Smithson, or Dan Graham employed mirrors in both performance and in static objects. Mirrors can foreground and transform space. The built environment can be a real conundrum in terms of the way different pieces act in conversation with each other. For me, space, object, and idea are inseparable, and I view architecture in perhaps a strange way as the creation of an object. Sometimes it’s the fabrication of an object, while sometimes it’s the literal space that the object creates.

How so?

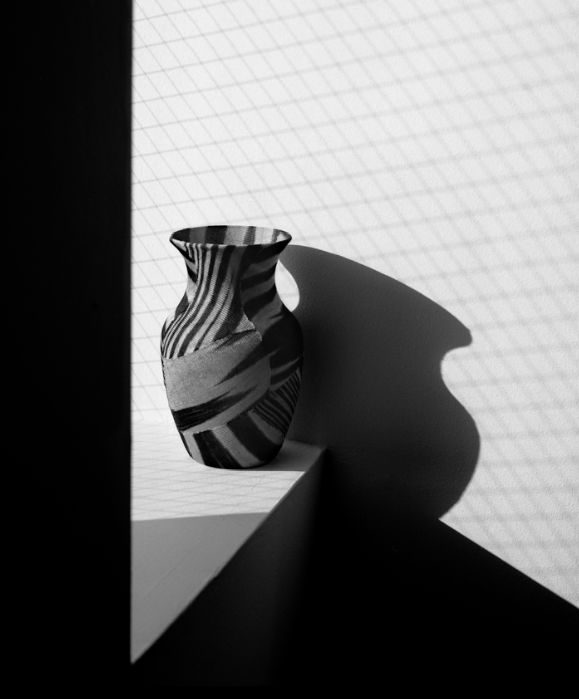

Take for example the System of Display series (2008–09), which features works that are mirrored or fabricated in printed glass. The objects themselves create a three-dimensional space within the gallery, but the gallery is of course its own space, another site, that has to be reckoned with. For me, the object itself is not finite or complete, it’s really a point of departure. It’s this idea I always come back to, which is about viewing the object as a site of engagement. I’m interested in finding a mid-space location, which is maybe how revolutions start.

Taken from PIN–UP 18, Spring Summer 2015.