FOUR TYPOLOGIES OF GARDENS

Nearly every culture in human history has found it necessary to construct a vision of paradise. Eden, Arcadia, Elysium, Shangri-La — no matter the name, paradise is an idealized notion of what could be, or what once was before sin, hubris, and human failing ruined things forever. Throughout the ages, the rich and powerful have always attempted to recreate a little piece of paradise on earth, charging the gardener and the landscape architect with wresting a semblance of order out of nature’s chaos. Historians date the earliest outdoor enclosures to around 10,000 B.C., rudimentary gardens that were cultivated in west Asia. Gradually the practice spread across the globe, assuming different forms to reflect the religious and political values, social hierarchies, and aesthetic preoccupations of the civilizations that sought spiritual refuge in the green spaces they created. So important are gardens to humankind that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon counted among the seven wonders of the ancient world, and the aura of great gardens has continued to stir the imagination in the centuries since, from the Moorish delights of the Alhambra in Granada, to the Renaissance charm of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, to the Baroque splendors of Versailles. To pay homage to the glorious history of global garden design, PIN–UP asked the visual artist Tom Hancocks to create four imaginary gardens, each one representing a hybrid version of a particular garden typology from the past millennium. In Hancock’s fantasy landscapes, the legacies of the two French Andrés — Mollet and Le Nôtre — meet to create the perfect jardin à la française; the gardens of the Alhambra enter into symbiosis with the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore; the English gardens of Stourhead meet the Prussian Romanticism of the Pfaueninsel in Berlin; and different traditions of Japanese, Korean, and Chinese rock gardens merge in mineral unity. Each imaginary garden reflects a particular historical approach to the cultivation, enclosure, and reordering of outdoor space. The results are a kind of compendium of major philosophies in the garden designer’s art, as well as a tribute to some of the world’s most majestic gardens, past, and present.

Landscape Garden

In the 18th century, in reaction to the hyper-manicured gardens of the continental aristocracy, the British invented the “landscape garden,” which idealized a wilder beauty, more naturalistic and more in tune with the topography of the given site, but ultimately just as calculated as its predecessors. Partly inspired by the Arcadian landscapes of painters such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, these bucolic confections feature poignant vistas punctuated by distant objects intended for wistful contemplation. Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the style spilled back into continental Europe and across the Atlantic, informing the sensibilities of the great American parks to this day. The Formal Garden

The manicured French garden, an evolution of the 15th-century Italian-Renaissance garden, sought to bring order and harmony to the chaos of nature. The designers of these über-formal gardens used military engineering to create vast axes and geometrical plans, which were decorated and regimented with parterres of pirouetting broderies, miles of hedges, and endless avenues of trees. The style found its apotheosis at Versailles, and less high-maintenance versions of it remained popular for centuries (and indeed, to this day) among the European aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Like its Italian antecedent, the formal garden exults in its interpretation of classical ideals of order and beauty, with a subtle note of sensuality forming a counterpoint to the strict Cartesian geometry.

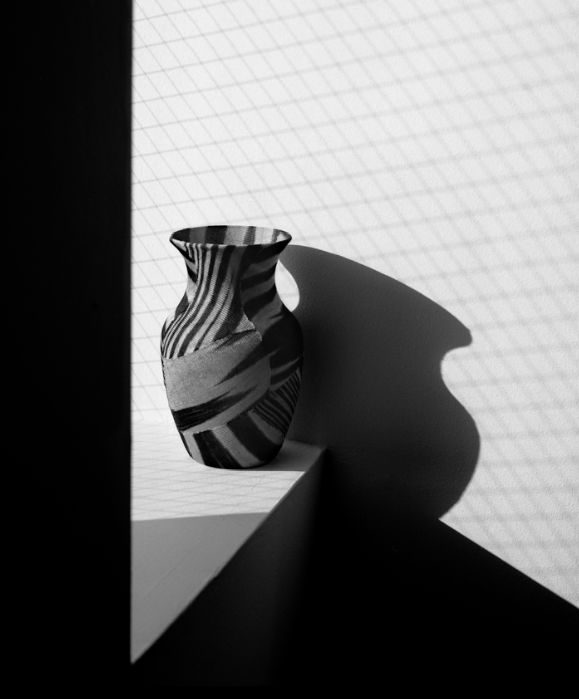

Rock Garden

In the Far East, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese garden virtuosos embraced the organic forms of rivers and mountains and distilled them into abstract forms. Classic Chinese gardens are often oriented around a series of unfolding and meticulously composed views that recall landscape paintings, and frequently feature evocative “scholar’s stones,” natural marvels of erosion that are used to symbolize mountains. The rise of Confucianism in Korea likewise kindled an interest in suseok stones, while in Japan Zen karesansui gardens emerged as masterpieces of austerity, where suiseki stones are fastidiously arranged amidst a calm sea of raked gravel. In the most refined Japanese Zen gardens, stone entirely dominates, vegetation being limited to moss at the base of the suiseki, while the delicate blossoms of briefly flowering trees are allowed merely to peek in from beyond the garden’s walls.

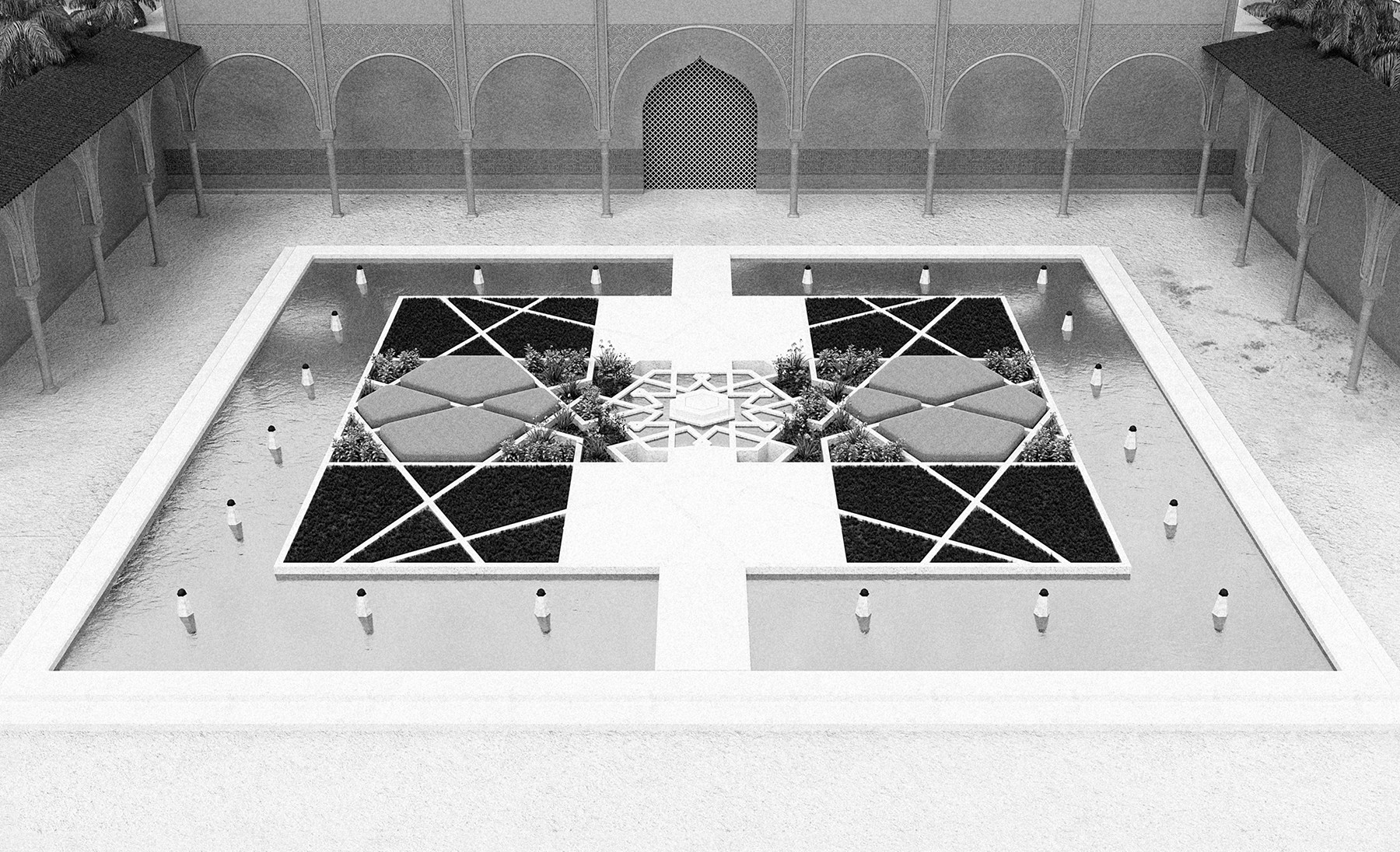

Islamic Garden

In one form or another, what has become commonly known as the Islamic garden has manifested itself from the Pakistani plains of the Indus River to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Andalusia, and beyond. The etymology of the term “paradise” can be traced back to the ancient Iranic language Avestan, whose word for “enclosure” or “park” was pairidaeza. The Islamic garden’s characteristic formal geometries and elaborate, decorative irrigation systems can be traced back to the Achaemenid Empire in pre-Islamic Persia, in the 6th century B.C., where kings showed their power by creating fertile enclosures out of the barren land, bringing symmetry and order out of chaos, and duplicating the divine paradise on earth. In the Islamic garden, architectural elements such as water features, arcades, and kiosks (a word derived from the Persian and Turkish for “pavilion”) provide shade and respite from the climate.

Text by Kevin Greenberg. Artwork by Tom Hancocks.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 20, Spring Summer 2016