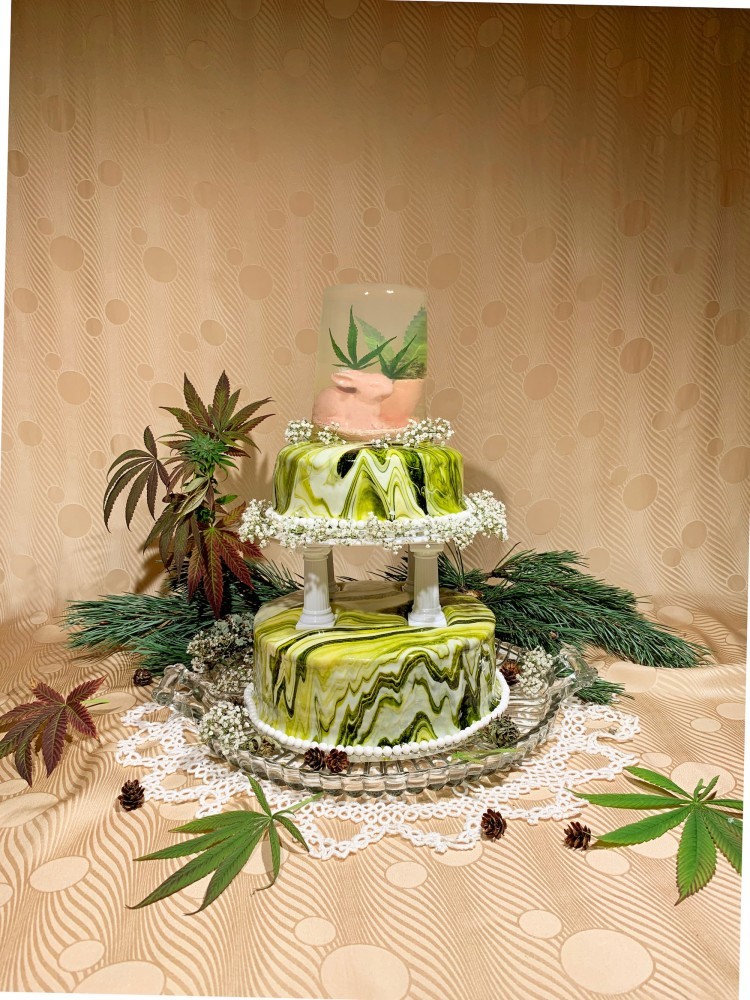

The Politics Behind Sharona Franklin’s Sculptural Jelly Cakes

Sharona Franklin is perhaps best known for the botanical jelly sculptures she shares on Instagram as @paid.technologies, her edible gelatin creations enveloping ethereal plant life like flowers, thistles, or weed leaves. Born with a rare degenerative disease, the Vancouver-based artist suggests there’s a parallel between her translucent works and her efforts increasing visibility for disabled artists. She also makes a parallel between the fragility of the gelatin and that of her own body. In her upcoming show New Psychedelia of Industrial Healing at Kings Leap gallery in New York opening February 29, Franklin uses ceramics and textiles as well edible works to explore her relationship to both new-age wellness treatments and the inherently masculine biopharmaceutical system, examining ideas of healing and the thorny ethics surrounding sometimes controversial medicines made from human and animal cells. Subverting the domestic associations of craft, Franklin’s new works include a tapestry quilt, dinner plates, and a 17-inch tall jelly sculpture, her most complex yet, which will be left to decompose over the course of the show, offering an example of what an organic degenerative condition looks like.

Canadian Thistle Jelly with Heliopsis and Baby’s breath on a paper maché armature.

Vivien Lee: You’ve mostly been known for your gelatin cakes, but you’ve also published written work, and now you’re making ceramics. How does medium play into your examination of medicine?

Sharona Franklin: I grew up on a street called Pottery Road and made clay stuff as a kid, but this is the first time I’m showing pottery. At the turn of the century, poetry used to be written on plates, so I decided to write poems on mine. I talk about sustenance and how some people can only be sustained by biotech. So it’s a play on what’s digestible for people. The medicines I take are made with human and animal cells, so a lot of work in the show is about those treatments and antibodies that are ingested intervescularly. It’s complicated because I’ll have this cake in my fridge that people love, yet the medicine right next to it that some people have an aversion to is what sustains me and lets me make these cakes. It’s a play on desiring the physical product of a person without considering the body, and how things need to exist for a person to produce something.

When did you begin to think of your treatments as being bio-rituals?

From such a young age, the thing that was precious to me was spending time with medical treatments. A lot of religions like Buddhism and Ayurvedic practices are anti-animal use, and originally I turned to these religions that matched my spiritual beliefs but not my medical practices. So it’s been a bit of a challenge, rather than thinking of them as spiritual rituals, I think of them as more as bio-rituals. There was a lot of confusion around these treatments and being judged for them, so I hit a point where I wanted to do a radical acceptance project. Rather than hiding it, or feeling excluded by having dinner with friends and rushing home to do my treatments, I decided to give them visibility.

Psychedelic glaze on an Aleppo Pepper, ginger, cayenne, cocoa, vanilla melt cake with spicy candied ginger buttercream, ginger beer floral jellies and lychee basil seed jellies, topped with ginger beer jelly filled white chocolate shot glasses.

Do you have to go to a doctor to get treated?

I receive my treatments in styrofoam packages from Sweden and they don’t go through a pharmacy here, so there’s a lot of invisibility around what they are and unless someone lives with me, they don’t understand it. I know there’s other people who experience the same things I do, but the problem with rare diseases is that it’s hard for people who have them to be understood. I spend time with treatments in a mindful way, which I hadn’t before. When I was a kid, all my medicines said “keep away from children.” There’s this idea that needles are bad, but it isn’t true. They’re a lifeline for so many people.

How do psychedelics play a role in living with your condition?

I started using psychedelics for escapism and trauma-related stuff when I was 11 or 12. I always use psychedelics as a radical therapy method. When I was younger there was no media or pop culture reference for me to exist within, so I always thought it’d be cool to be able to see art books with treatments in them. Some people think of psychedelia as something new and amorphous. With the project, I’ve been trying to allow a new world to exist.

Do you eventually want to make radical children’s books?

Yes, I want to make a storybook about having an illness as a kid. I think that’s also why I put my writings on plates. It’s like being served a treatment. I like putting objects in unexpected places. Antibodies are so interesting because they’re body naturalized but invisible to people.

Can you expand on the significance of antibodies for this show?

Antibodies change the way my body reacts to genes. It changes the function of my genes. With veganism too, a lot of people don’t realize a lot of medication comes from pigs, etc, and are produced with animal cells. I think that’s what’s interesting about bioethics because at what point does an animal prioritize the life of an ill child? There’s a lack of understanding and cross over. Treatments are privilege, it helps people understand barriers that people might face.

-

Otherworldly prosecco rosehip tea jelly delights.

-

Psychedelic glaze on an Aleppo Pepper, ginger, cayenne, cocoa, vanilla melt cake with spicy candied ginger buttercream, ginger beer floral jellies and lychee basil seed jellies, topped with ginger beer jelly filled white chocolate shot glasses.

Do you ever talk about the type of drugs or treatments you take? I can understand it’s a sensitive topic.

Yeah, it can be hard because not everyone understands them or what they are. Some of the meds I take now are used on the black market for abortions. Some of these drugs are used for different purposes in different regions. This regionalism is big with psychedelics too. There’s this organization in California called MAPS, Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, and they’re working on MDMA therapy treatments. Ketamine for depression can be used in certain places but there’s red tape in others. The problem with rare diseases is that there’s not many people to be tested on, and not many people to sell them to.

What are some of the points around femininity and labor as a disabled individual that are also prevalent in your work?

A lot of disabled people are homebound which inherently makes you domestic but the domestic things you have to do are difficult for you. You’re surrounded by blankets and food if all you do is sleep and eat, but acquiring food and cleaning your bed can be impossible. As a kid you’re being told that no one’s gonna marry you or that you can’t be a mother. It has a lot to do with class.There’s never representations of ill people or kids in the media unless it’s a tragic Hallmark story. If you can’t get a great education because you’re ill then you get these labor heavy jobs because that’s all you can get, so a lot of institutions aren’t disability-forward. Most of my disabled friends haven’t finished school.

You mentioned you’ve written a lot about food in most of your poems. When did you develop an interest in food and cooking?

As a kid my parents didn’t have much money so food was all we had to think about. I used to clean houses and my mom did too, sometimes I skipped school to clean houses with her and it was very survivalist because (securing) food was the first issue we faced. In the winter it’s harder to get fresh produce in Canada where I am from, so especially fresh food was something I didn’t have access to. I didn’t have television but my grandma had one, and she’d record cooking channel shows on VHS. My dad cooks and hunts and traps animals, so I also learned a lot from him.

Ecstasy Cloud Lime Jasmine Cloud: cake with lime peak sponge, lime curd swirled into jasmine icing, and gold fleck peach white tea mini moon jellies and handmade gold fondant, for @soulmistresssupreme’s birthday.

That’s a heartbreaking story, but it makes a lot of sense why you emphasize the digestible being political. What does biocitizenship mean to you and your relationship to food and medicine?

For me I think about the soil that our food comes from, the air and the water that we drink, how our blood is sustained. I grew up with well water and a lot of these things affected our health. A lot of people in Flint or the Appalachians have such poor water and food sources, so illness and low education rates are high. There’s also the aspect of access to medication. Some medications are distributed through manufacturers, others aren’t. I can’t take medications in certain countries because they’re not legal or provided there. Biocitizenship connects your citizenship to your body and underscores how you’re reliant on these bureaucracies.

Interview by Vivien Lee.

Images courtesy Sharona Franklin and Kings Leap.