EARLY ERGONOMICS: Designer Bill Stumpf and the Science of Sitting

Inventor Bill Stumpf had been studying the way people sit for years when in 1974 Herman Miller commissioned the designer to apply his scientific research to office seating. Two years later, the game-changing Ergon chair was born. Concluding our three-part series highlighting the comprehensive new book Herman Miller: A Way of Living, industrial designer Leon Ransmeier (who edited the book together with Amy Auscherman and Sam Grawe) walks us through the transformative effects of Stumpf's approach to ergonomics and the office chair. Herman Miller’s shift toward science-based innovation is also chronicled in an exhibition currently on view at the Herman Miller showroom at 251 Park Avenue South in New York (up until the end of July).

Eames chair prototype c. 1950s. © Eames Office LLC.

“This is an Eames experimental prototype from the mid to late 1950s that we discovered at the Eames Office. The design resembles Eames 670 lounge chair but more upright, and is evidence of the Eames Office considering the idea of luxurious comfort at the office. This would have been about ten years before Soft Pad, which was launched in 1969. The mainstream acceptance of active sitting and the ergonomic accommodation of work didn’t come about until the 1970s, together with word processing and information management. There was huge growth in the white collar workforce and the daily integration of technology into the office which more than ever required people to be seated in one place.”

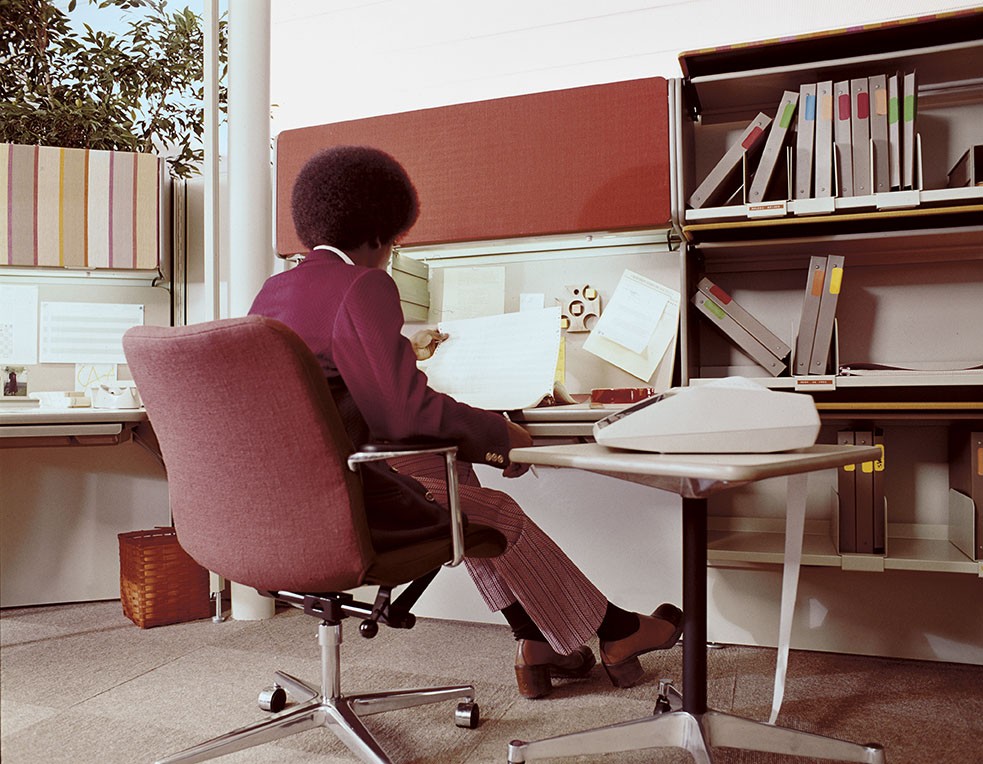

NS 106 Light Office Seating designed by George Nelson, 1971.

Credit: Courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives.

“This is an image of a man sitting on the Nelson lightweight chair that Herman Miller introduced in 1971. Despite being somewhat innovative in its construction, it was not very successful because it was a bit ugly and kind of expensive.”

Ergon “operational” chair with mannequin, 1976. Courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives.

“This is an outtake of an early campaign for the first Ergon chair, which was launched in 1976. Kevi, Wilkhahn, Olivetti and others were all making chairs that were somewhat ergonomic, but almost no one was researching ergonomics in seating at the level that Stumpf was. His process involved copious data collection, X-rays, and product testing. He had written his masters thesis about the subject. One of his criteria was that the chair would support your body in a wide variety of positions — whether you are reclining and slouching or leaning forward with your legs pushed up against the edge.”

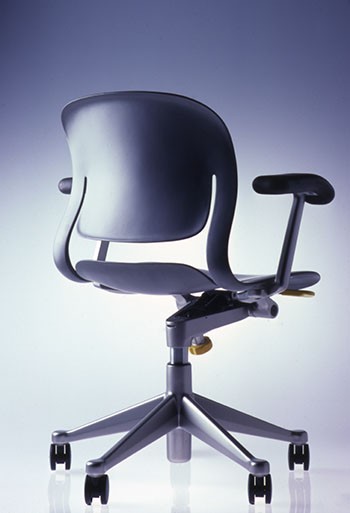

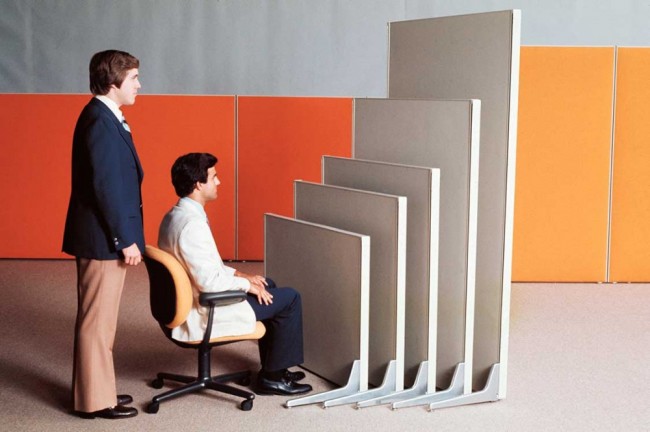

Rollback chair, 1976. Courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives.

“This is Ray Wilkes’s Rollback chair from the same year, also 1976. Wilkes’s most famous Herman Miller product is the Chiclet sofa. This chair came out the same year as the Ergon chair and was a misguided attempt at ergonomics but still an interesting piece sculpturally. The most striking aspect is probably the die-cast aluminum base which I jokingly call the squid foot. It’s innovative because there are casters obscured under the globes, but also hideous. I just wanted to include this chair because I’m in awe that it was actually produced.”

-

Don Chadwick holding experimental Equa shell with filled slot, c. 1981. Courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives.

-

An image of the Equa chair from the journal A Serious Chair, 1984. Image from the collections of the Henry Ford.

“Originally Stumpf was assigned to work together with Don Chadwick on an office system called BuroPlan, a very postmodern system. Their manifesto sounds almost like Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, they suggest bringing vernacular symbols and domestic familiarity to the office as the goal. The system never made it to production but one aspect that survived was what they called ‘humanomic seating.’ In their words, they wanted their seating concept to ‘synthesize the aesthetic elegance of Eames chairs, the comfort of the Ergon chairs, and a new level of ergonomic and technological simplicity.’ The program became Equa. The first image here is an early prototype at Chadwick’s office — you can see the palm trees. While Stumpf was based in Minnesota, Chadwick was in LA and stills lives there to this day. The second image comes from an issue of a journal published by the Walker Art Center in 1984 called A Serious Chair, that accompanied an exhibition of the same name.”

Sarah chair mechanical prototype developed by Don Chadwick and Bill Stumpf, c. 1987. Image from the collections of the Henry Ford.

“This is the Sarah chair. In the late 1980s Herman Miller began a program called Metaform and hired a number of different design offices, including Stumpf Chadwick & Associates. They developed the Sarah Chair as part of a design for an entire house for elderly and handicapped people. I like this image a lot because I think it says a great deal about how complexity and comfort are related. Sometimes the more comfortable and easy to use something is, the more complex the engineering needs to be. Stumpf liked to quote the novelist and philosopher William Gass who once described comfort as “a lack of awareness” — you’re not thinking about the fact that you are doing something because you are so comfortable. With the Sarah chair, they researched aeration to help people who were sitting all the time not develop skin disorders. The Sarah chair’s breathable textiles and stretched mesh later became a starting point for the Aeron chair.”

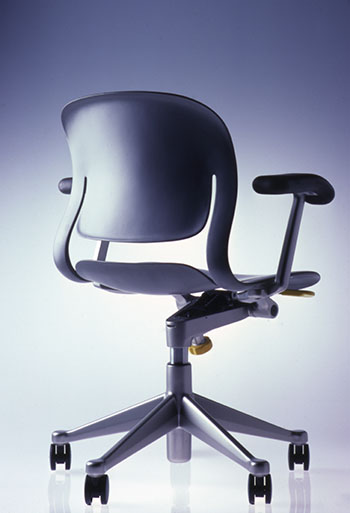

Aeron chair prototype, c. 1991. Image from the collections of the Henry Ford.

“This is one of the first prototypes of the Aeron chair. In this particular iteration, it’s reminiscent of an Eames Aluminum Group chair. The base and tilt are from an Equa chair and they’re experimenting with side profiles and the stretched mesh. What I like about this image is that it’s an early prototype of one of the most famous chairs ever created and probably the best example of a chair being designed as a piece of equipment. And still, the prototype looks rough, almost as if it could have been made by Jessi Reaves.”

Experimental Aeron frame with prototype suspension textile, c. 1992. Image from the collections of the Henry Ford.

“This is another prototype, maybe a little over a year later. You can see the frame is more or less in its final design and they’re just playing around with the pellicle, the trade name that Herman Miller uses for the woven mesh that is molded into a frame and then attached onto the chair back and seat. For a chair nerd like me, this is a beautiful image. You have this very basic wooden structure supporting a very technological innovative, breathable biomorphic form.”

Text by Leon Ransmeier as told to PIN–UP.

Images courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives unless otherwise noted.