MACHINES FOR DANCING: Club Design and the Evolution of Desire, Seduction, and Utopia

What does it mean for a museum to stage an exhibition about club culture and design in 2018? For a generation more familiar with Berghain than Studio 54, the concept of tasteful club furniture must seem in diametric opposition to the carnal smut of the post-industrial warehouse, which has become everyone’s idea of the contemporary nightspot. Yet design and clubbing are entwined in many surprising ways, as revealed in Night Fever, the latest exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany. Subtitled Designing Club Culture, 1960–Today, it was curated by Jochen Eisenbrand with Catharine Rossi and Katarina Serulus, and features scenography by Konstantin Grcic and lighting by Matthias Singer. As the subject of design, in fact, the nightclub can be considered an immersive canvas for active participation by users willing to play with codes of behavior; and while clubs have become an increasingly threatened species in today’s economy of instant commodification, many of them continue to prove that it’s possible to foster and maintain their liminal or informal communities, even if only temporarily.

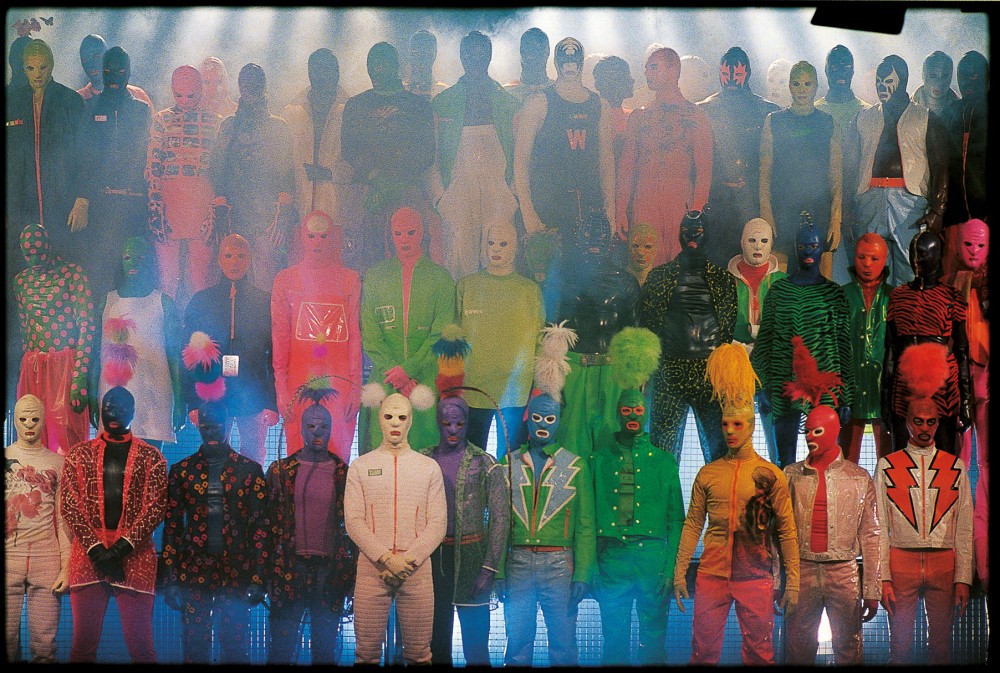

Walter Van Beirendonck, fashion show of Wild & Lethal Trash (W.&L.T.) collection for Mustang Jeans, Fall / Winter 1995/9. © Dan Lecca / Courtesy of Mustang Jeans.

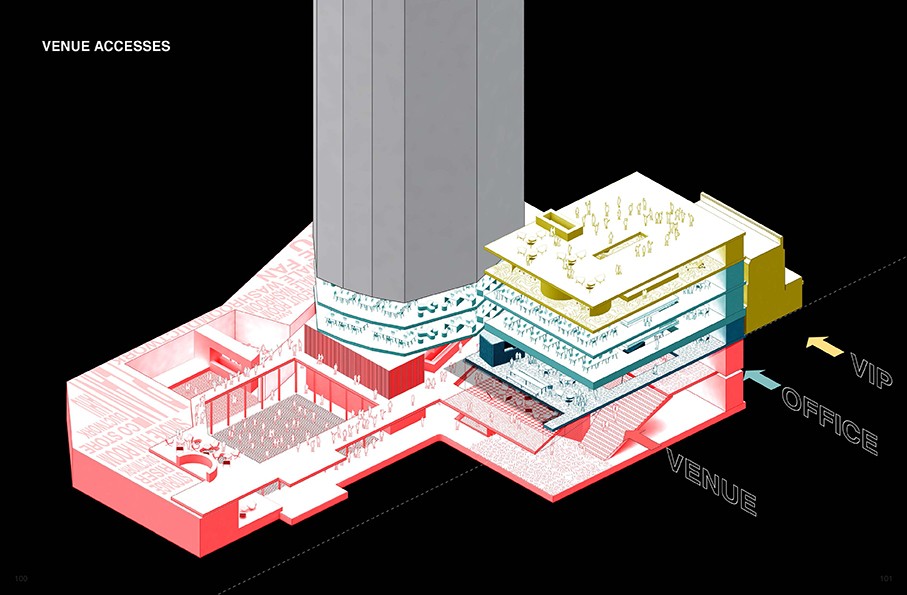

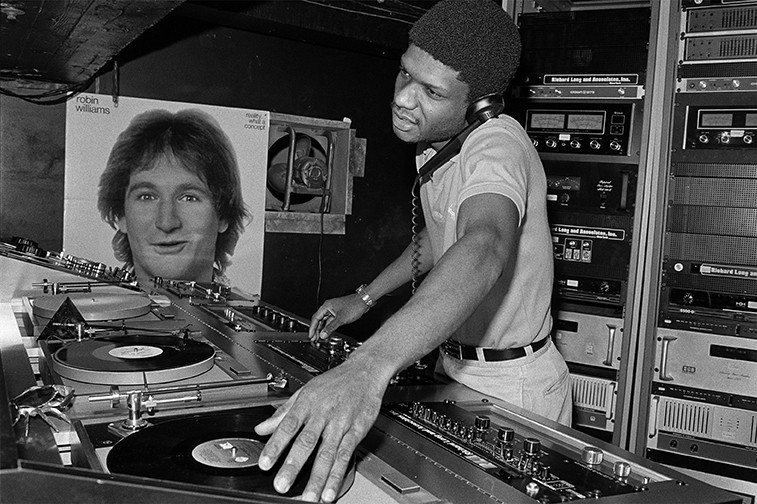

Dark, technologically saturated environments had served 20th-century designers as laboratories for enveloping spatial effects long before the advent of Area, the Palladium, The Saint, or Paradise Garage. At the 1964 New York World’s Fair, Charles and Ray Eames designed the IBM Pavilion as a place for multimedia entertainment through non-linear narratives, including simultaneous film clips and sounds that celebrated the relationship between humans and machines. At the same time, in Italy, radical young architects like Gruppo 9999 and Studio65 were designing the first discoteche that we might recognize as the ancestors of today’s clubs. “In the Piper in Rome and Turin or Space Electronic in Florence,” says Eisenbrand, “the idea was to create multivalent, modular spaces that could be used for all kinds of activities — not only dancing but also performances and experimental theater.” Designers’ fascination for nightlife lingers on to this day — albeit in less youthfully utopian forms — in projects like OMA’s Miu Miu Club (2015), a temporary installation for Prada that was influenced by the firm’s proposed redesign of London’s legendary Ministry of Sound, which they’d wanted to “reinvent as a desire-making machine.”

Discotheque Flash Back, Borgo San Dalmazzo, ca. 1972. Interior Design: Studio65. © Paolo Mussat Sartor.

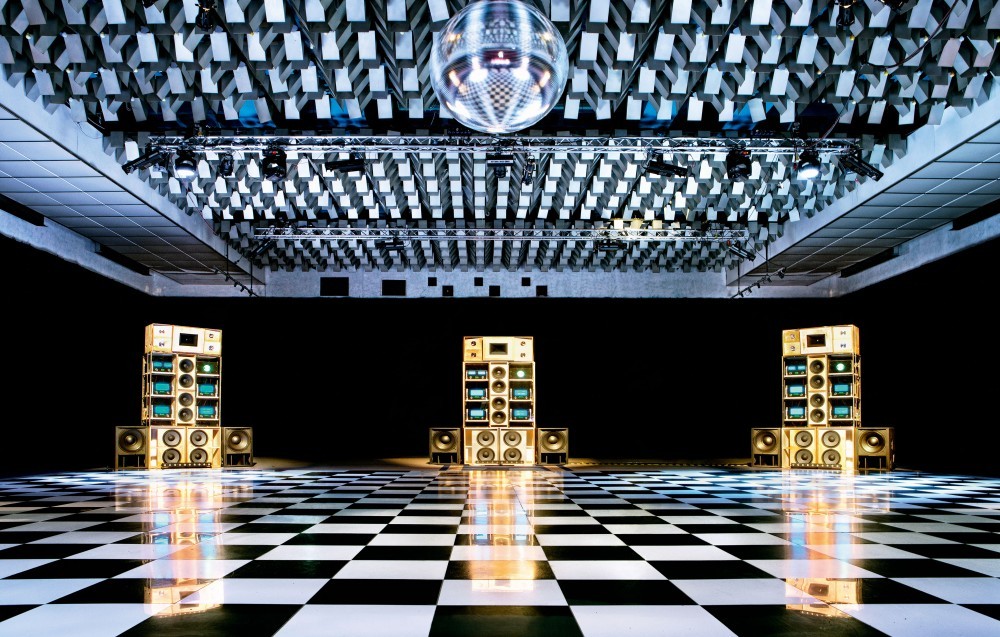

That affinity becomes particularly clear in the Vitra show’s highly comprehensive catalogue, which takes the form of a nightlife-design encyclopedia. Edited by Mateo Kries, it revels in the ability of design to create alternative spaces of interaction. While its many photographs cannot recreate the overwhelming power of music, strobe lights, and intoxicants, it does reveal the less-acknowledged role of physical materiality in creating a new protocol for club audiences. In particular, the pair of images that opens the book — on the one hand the ad-hoc aesthetic of rainbow projections for white-robed audiences at Cerebrum, photographed in 1968 by John Veltri, and on the other the sheen of the golden Despacio sound system reflected in the checkerboard tiles of Manchester’s New Century Hall in 2013 — shows the flexibility of design as both a methodology of urgency and an aesthetic of Surreal imaginaries.

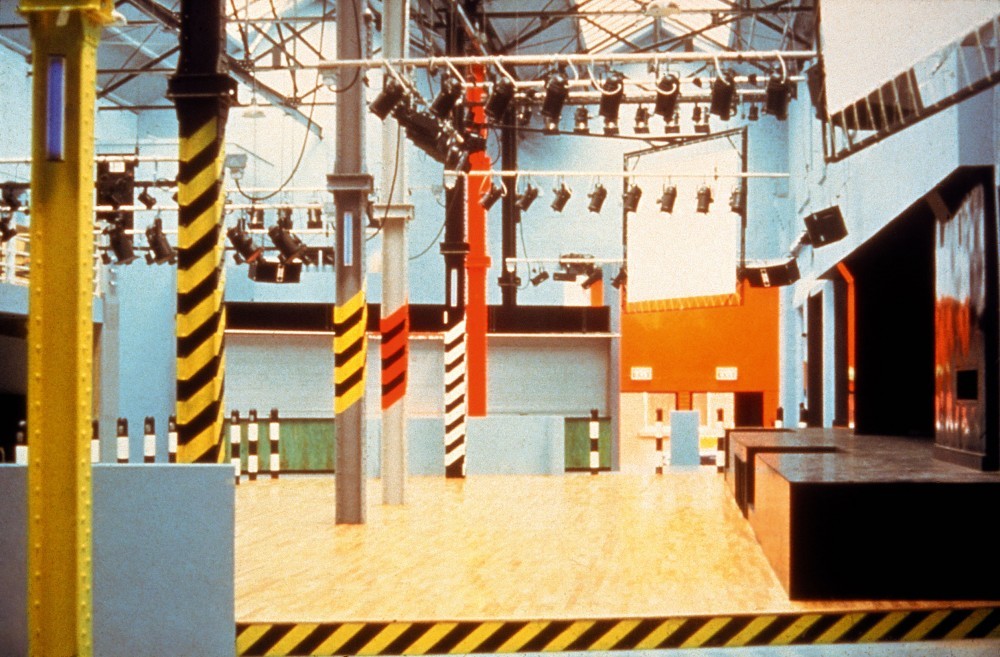

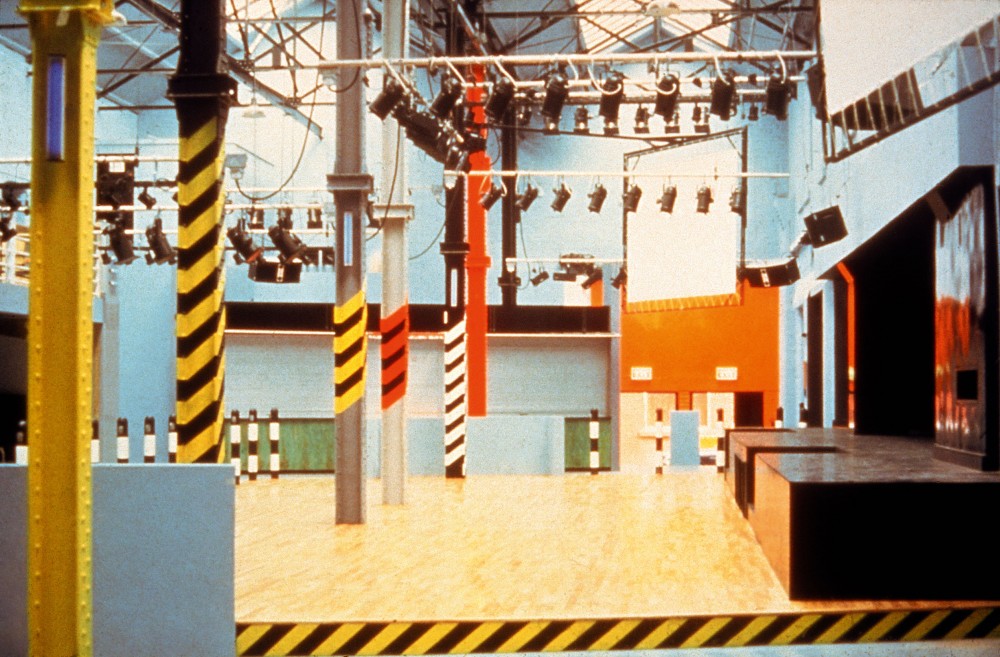

Interior view of Haçienda, Manchester. Courtesy of Ben Kelly.

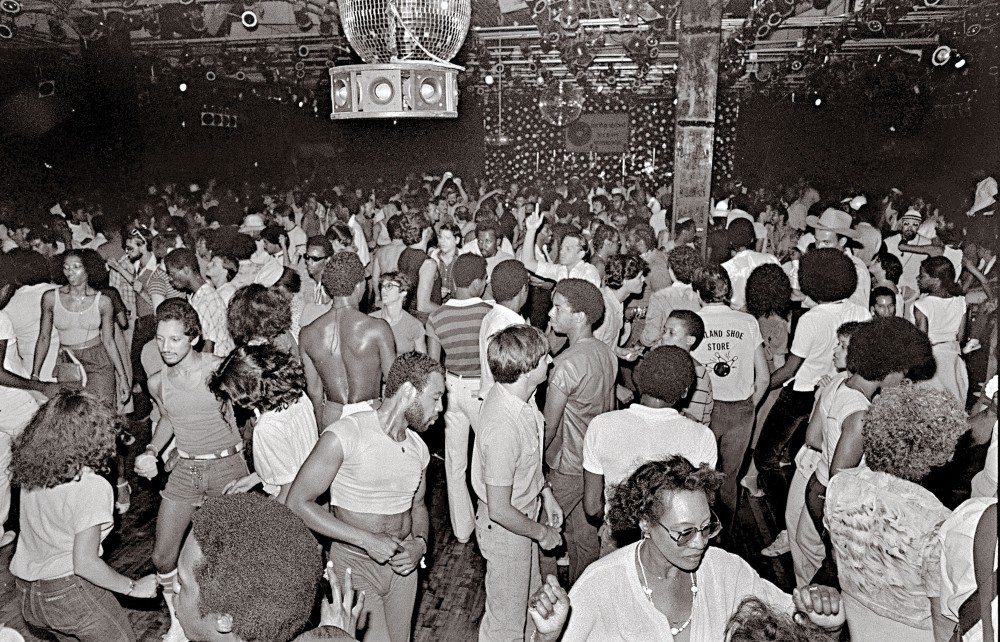

Another connection explored in the exhibition is the vulnerability of both industrial design and club culture to financial crisis and to the rise of ubiquitous networked high-resolution technology. The latter has largely obviated the need for physical presence or concrete objects in the provision of experiential entertainment. In fact, over the past few decades, nightlife has often inhabited the fossils of extinct or outsourced industries, from the old yacht showroom which became Manchester’s Haçienda (1982–97) to the former newspaper print house that was Trouw in Amsterdam (2009–15), not forgetting of course the converted power plant that is home to Berlin’s evergreen, the aforementioned Berghain (which opened in 2004). The Vitra show also highlights innovative social initiatives like the Mothership (2014), a mobile DJ booth designed by the Detroit studio Akoaki, in collaboration with members of Parliament-Funkadelic, as a way of uniting the popular appeal of the club and the architects’ sensitivity to urban fabric to foster unique local heritage in terms of music, dance, and buildings.

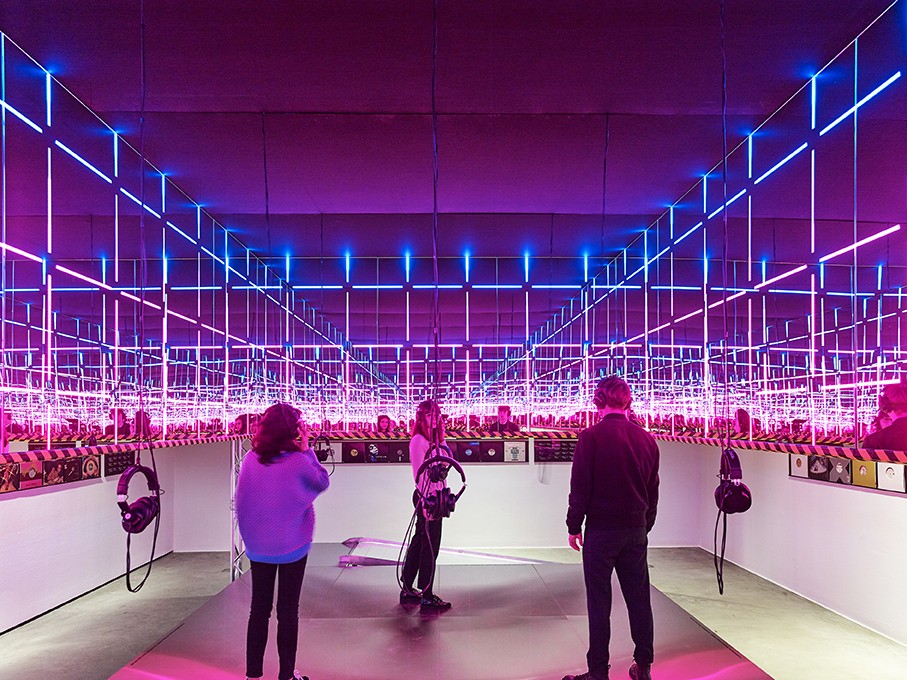

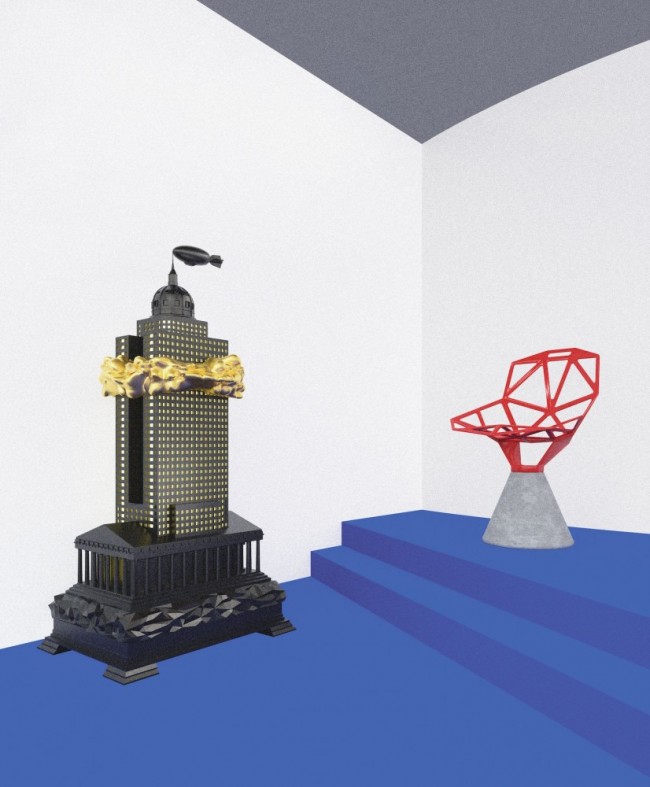

Night Fever installation view. Image courtesy Vitra Design Museum.

While architects generally claim a monopoly on spatial discourse, the club is one of the few places that non-designers are comfortable speaking about in terms of spatial and sensory qualities. It is also where we all consciously and subconsciously adapt our behavior in response to unusual conditions of lighting, visibility, texture, sound, and animation. “Going into a club for the first time, you never really know what to expect,” says Grcic, whose exhibition design muscles an entirely un-museum-like experience into the middle of the chronological narrative. “You see the crowd outside, you feel the bass pumping out through the walls of the building, and you enter that door — something surprising will happen.” In Night Fever, that surprise manifests itself as a space in which sound, light, and spatial effects take the place of archival documents in animating what the nightclub archetype means and how it frames and operates on the club-goer. “For that moment, the viewer forgets where they are — they are not in a museum, they are somewhere else,” Grcic continues. His scenography for Night Fever celebrates the simple beauty of the precisely functional, industrial objects found in clubs — galvanized-steel balustrades, elevated walkways, aluminum trusses — and uses them as recurring spatial elements. He also reimagines the loudspeaker box, with its tough, textured, black-lacquer surface, as a vitrine to showcase photographs and other display material. In so doing, he inverts the direction of aesthetic influence pioneered by Ben Kelly in the Haçienda, where exposed steel columns were painted in bold reds and yellows and floors marked with hazard stripes, in reference to Factory Records.

Musa N. Nxumalo, Wake Up, Kick Ass and Repeat!, photograph from the series 16 Shots, 2017. © Musa N. Nxumalo / Courtesy of SMAC Gallery, Johannesburg.

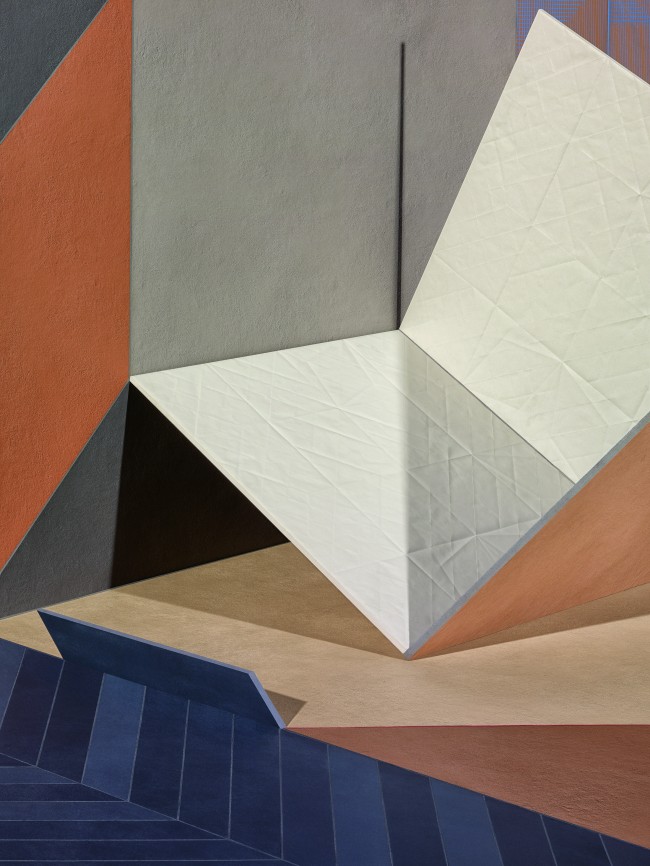

By transposing the visual language of the club to the sphere of the design museum, Night Fever pushes today’s design practitioners to learn from the urgency and avant-garde nature of clubs, even if they now have to look further afield to find that “explosive quality and revolutionary atmosphere,” as Eisenbrand puts it. Whether it’s the Johannesburg clubs documented by South African photographer Musa N. Nxumalo or the surreal atmospheres staged by contemporary Chinese artist Chen Wei, these spaces prove that, all nightlife nostalgia aside, a club remains the space where politics, performance, and the uncanny can intermingle through the lens of design.

Text by Tamar Shafrir.

Taken from PIN–UP 24, Spring Summer 2018.

Night Fever. Designing Club Culture, 1960–Today is on view at the Vitra Design Museum until September 9, 2018.