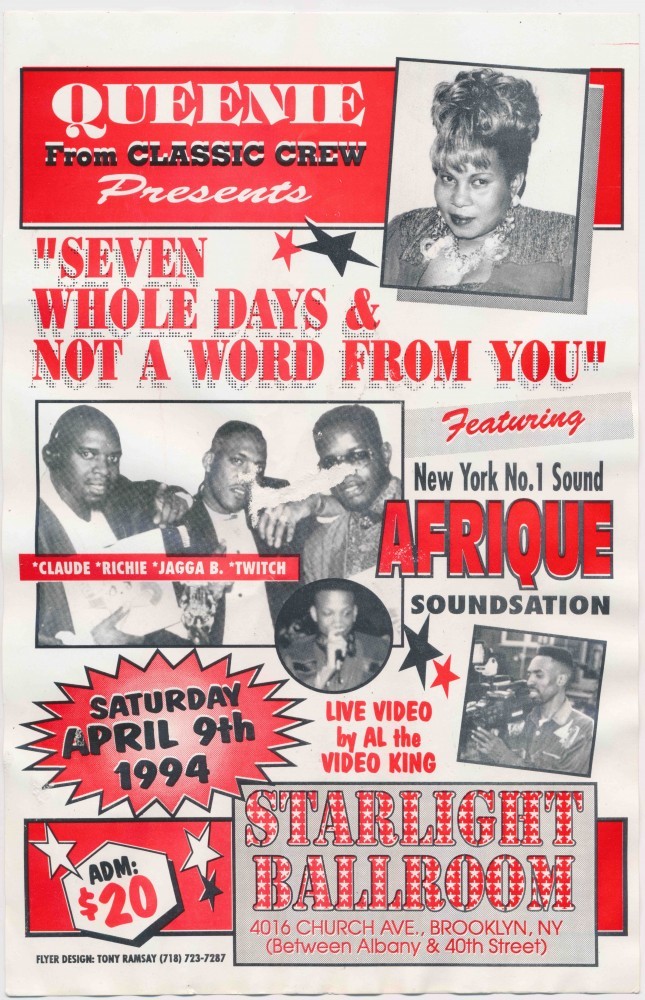

INTERVIEW: Akeem Smith On Recreating The Architecture Of Jamaican Dancehall

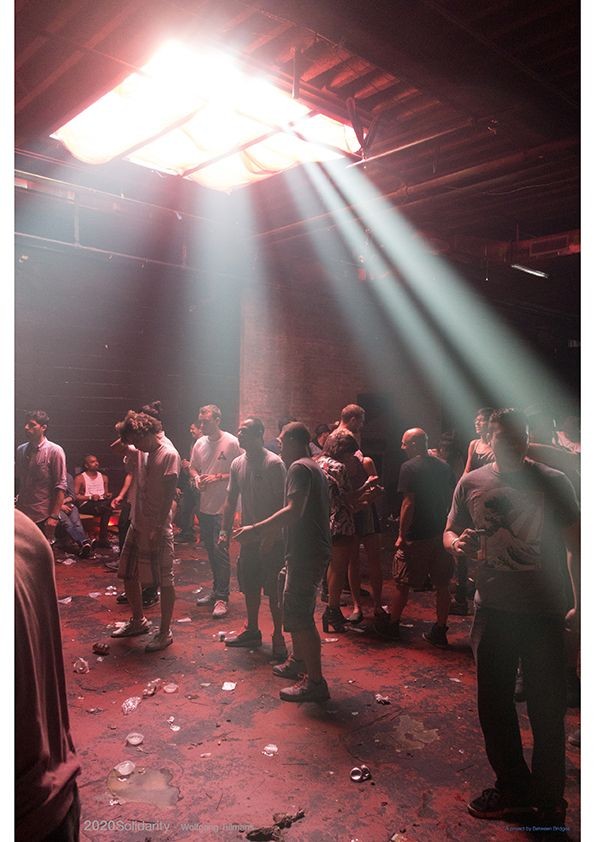

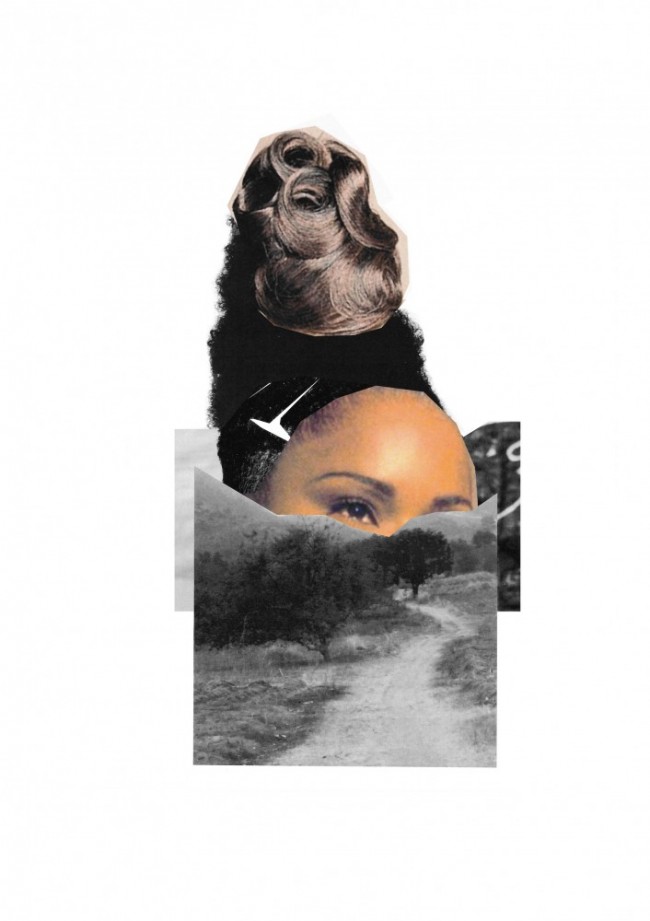

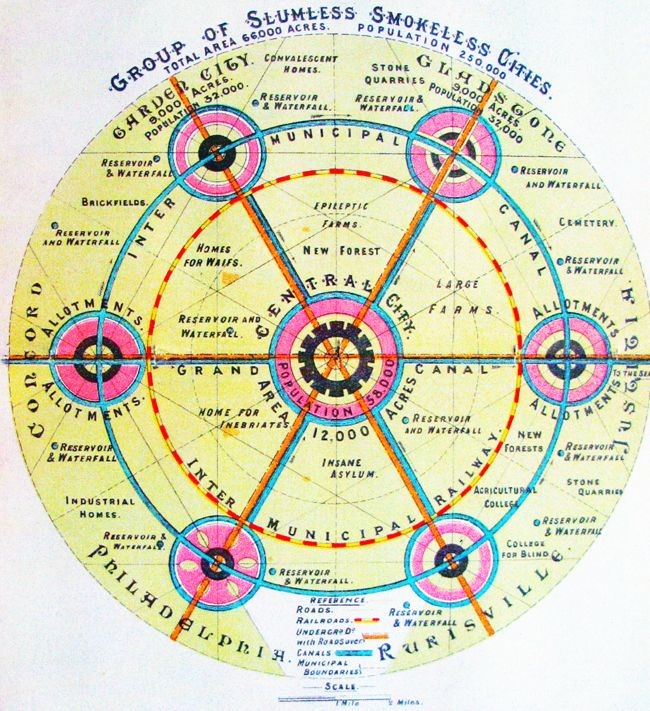

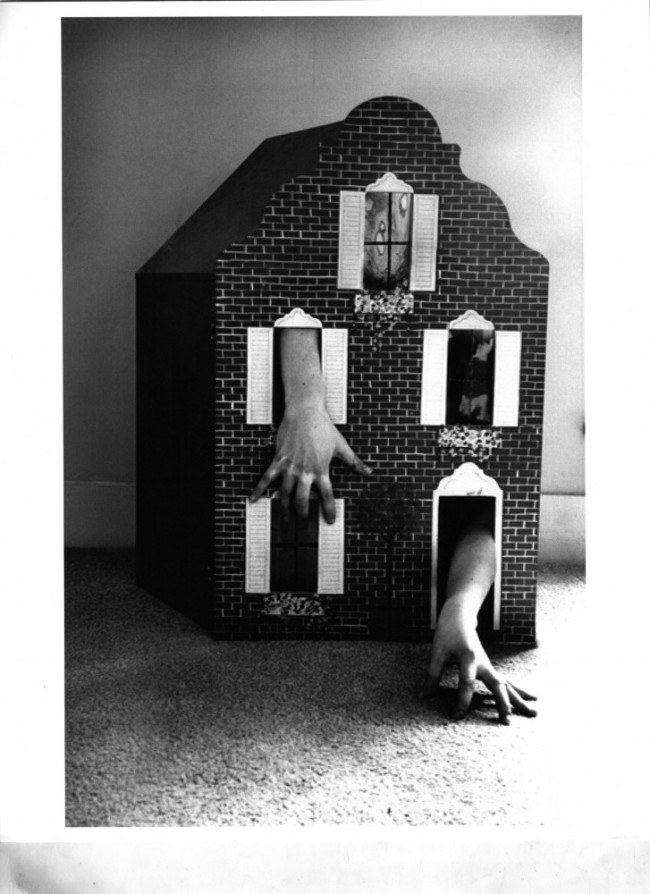

The artist Akeem Smith is the scion of the House of Ouch, the Jamaican fashion force founded by his godmother Paula Ouch who designed fearless looks for local dancehall parties. The exhibition No Gyal Can Test archived the scene’s community, which Smith grew up around, showcasing photos and videos from the Ouch crew’s heyday, from the late 1980s to the early aughts. But while the looks, videos, and music are impressive, it’s the architecture that really steals the show: Smith packed up and reassembled the spaces in which the parties took place and transformed them into walk-in sculptures, using paint-chipped walls, doors, and ornate cast-iron window grills, all of which he shipped directly from Jamaica to Red Bull Arts New York’s cavernous Chelsea location. Given the scope, it comes as somewhat of a surprise that the ambitious multi-floor exhibition is technically Smith’s art world debut. For most of his career, the 29 year old has been in fashion, quietly consulting for some of the most important players in the industry, discreetly styling big name celebrities, as well as starting his own line of womenswear, Section 8. But If No Gyal Can Test is any indication, Smith’s low-key days are over.

-

Akeem Smith, Soursop, 2020: Single-channel video installation, monitors, framed vintage photographs, salvaged building material, fabric, wood. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

Akeem Smith, Soursop, 2020: Single-channel video installation, monitors, framed vintage photographs, salvaged building material, fabric, wood. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

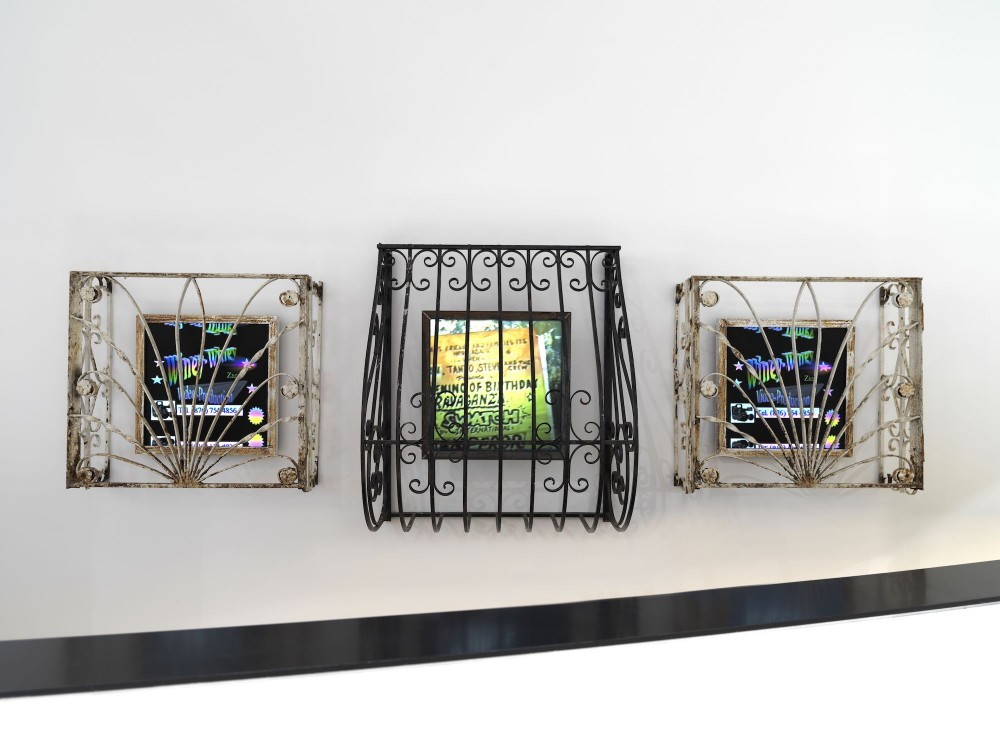

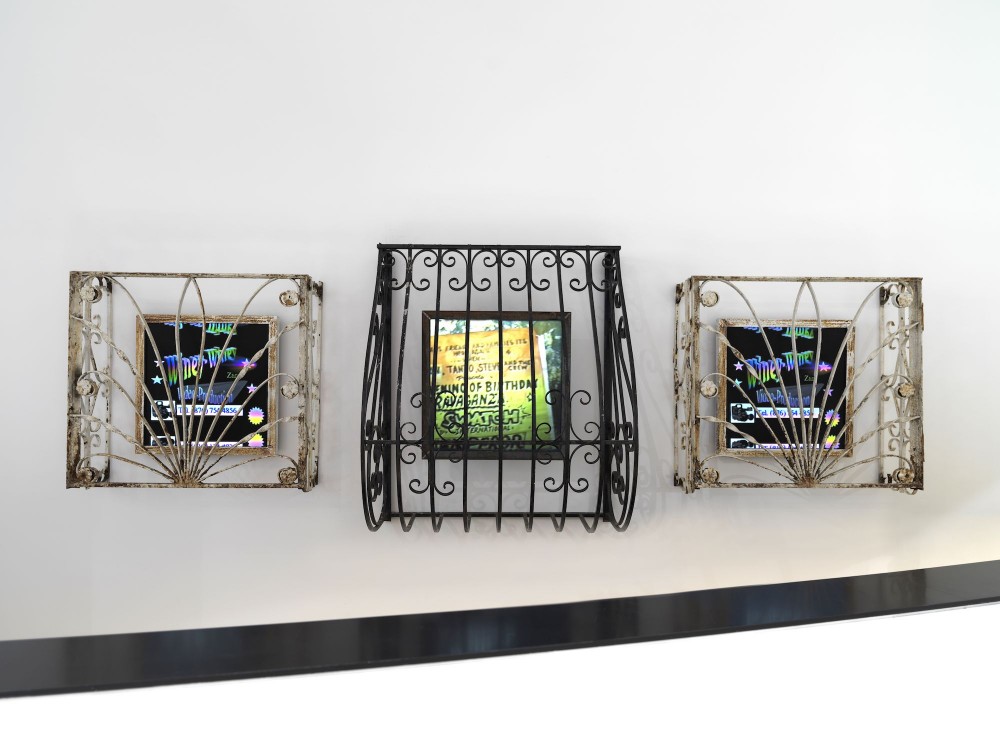

Akeem Smith, It’s the best to rise with a smile on your face/ just like the sunshine all over the place/ who god bless, no man curse,

2020: Three-channel video, monitors, salvaged window grates,

metal. Photography by Dario Lasagni. -

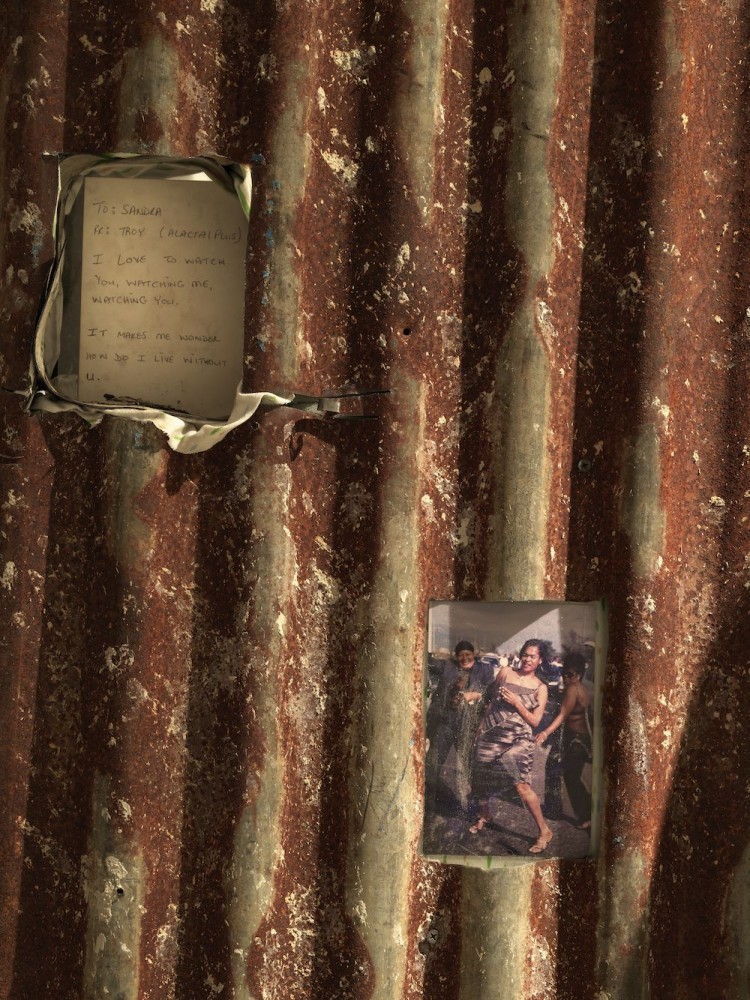

Detail of Akeem Smith, Altarpiece, 2020: Color photographs, salvaged metal, steel. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

Akeem Smith, Sugar Minott. 2020: framed vintage photograph, color photograph, salvaged building material, breeze blocks, wood structure. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

When did you start working on this show?

Twelve years ago, when I was 17 years old. I already had this idea for a show, but I didn't want to be an artist yet, at least not in a conventional way. The idea of the s how came first before figuring out my practice. I knew I had a bunch of great family photos and I thought people could get this view on what dancehall culture was about. I wanted to spread my knowledge without seeming like a cultural snitch. These days, it’s sort of hard to measure what should remain sacred and what should be informative. I think, with Caribbean cultural in general and dancehall specifically, it’s an oral history culture. This show is formalizing it a bit, but not in a way that is too academic. It’s through art. And it’s through first-person narratives — the people within the culture aren’t usually the people speaking.

-

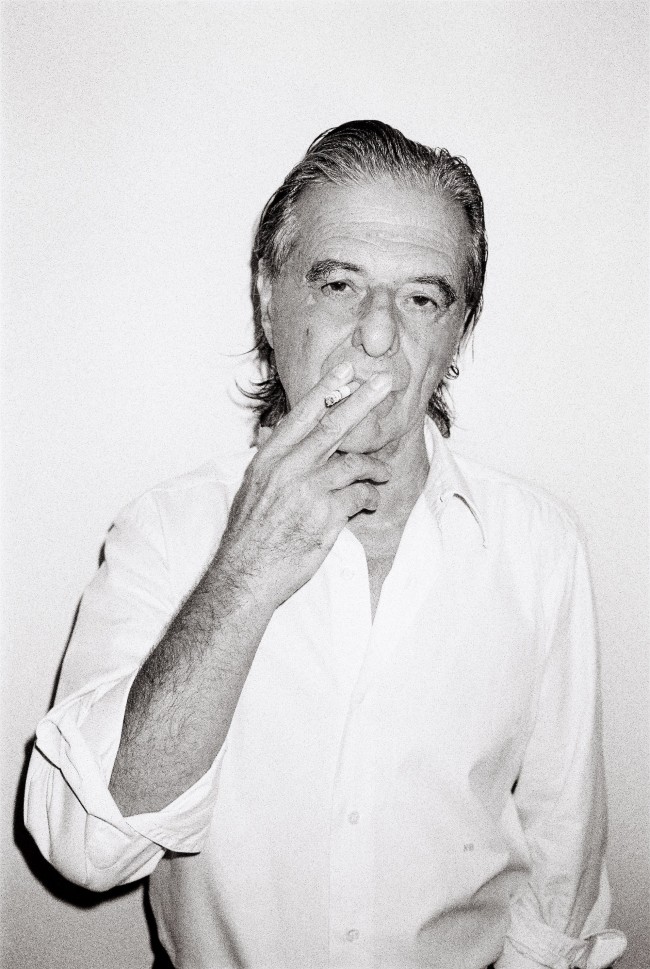

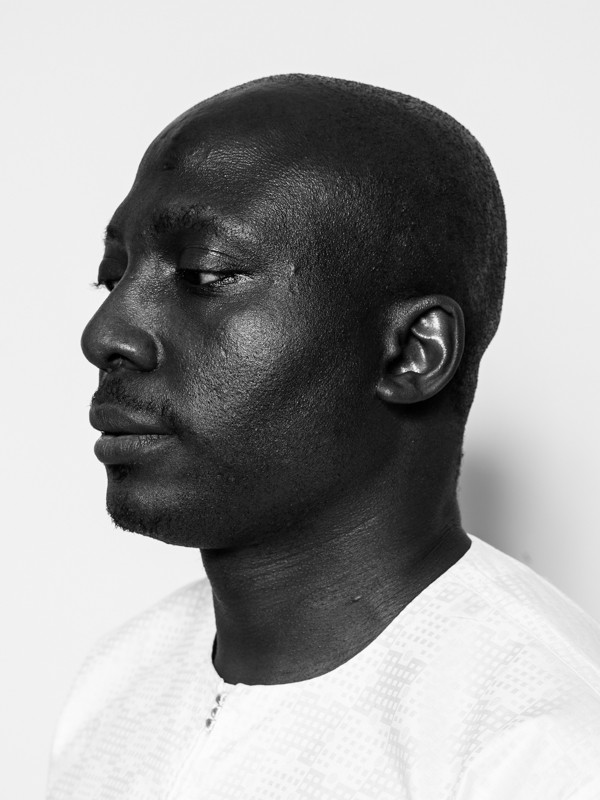

Akeem Smith photographed by Christopher Tómas for PIN–UP.

-

Detail of Akeem Smith, Soursop, 2020: Single-channel video installation, monitors, framed vintage photographs, salvaged building material, fabric, wood. Photo by Dario Lasagni

-

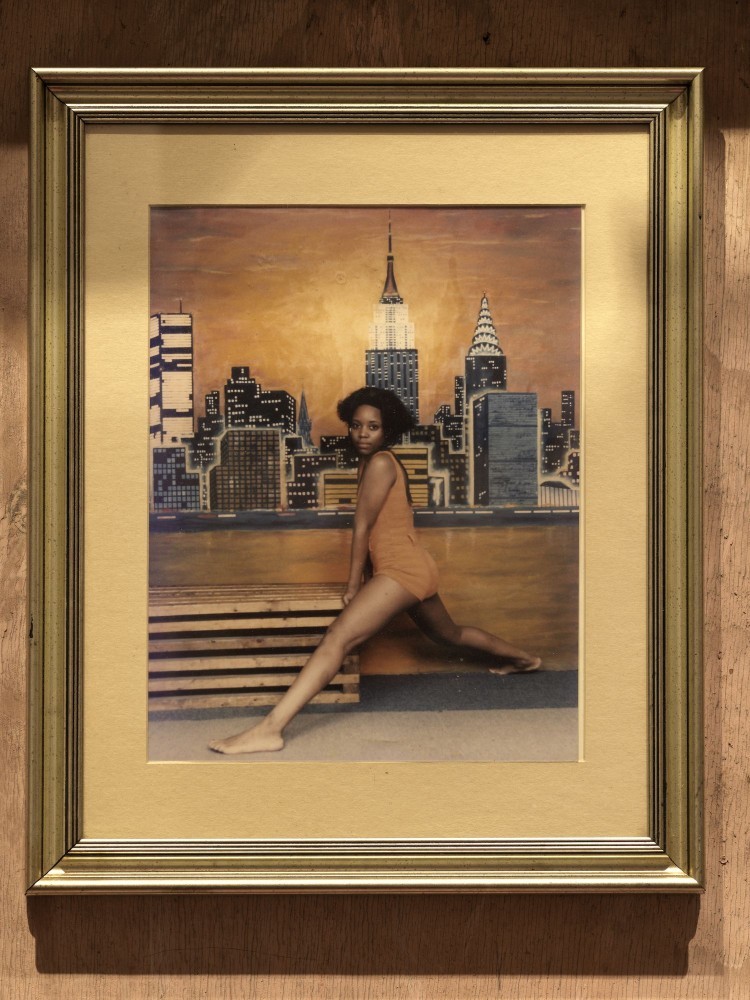

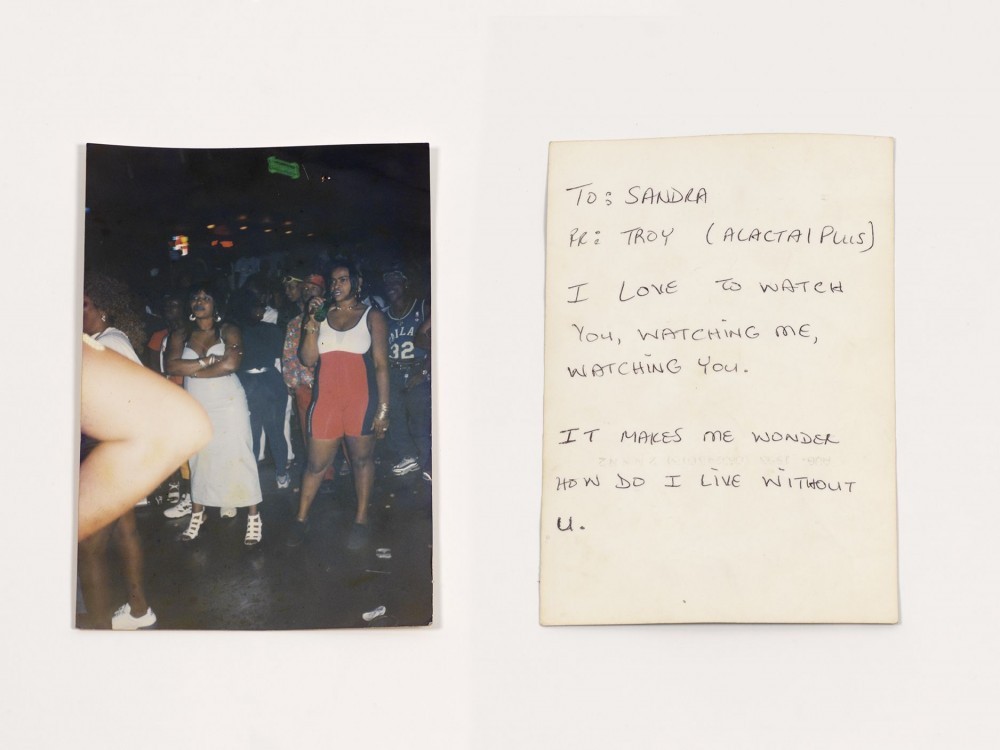

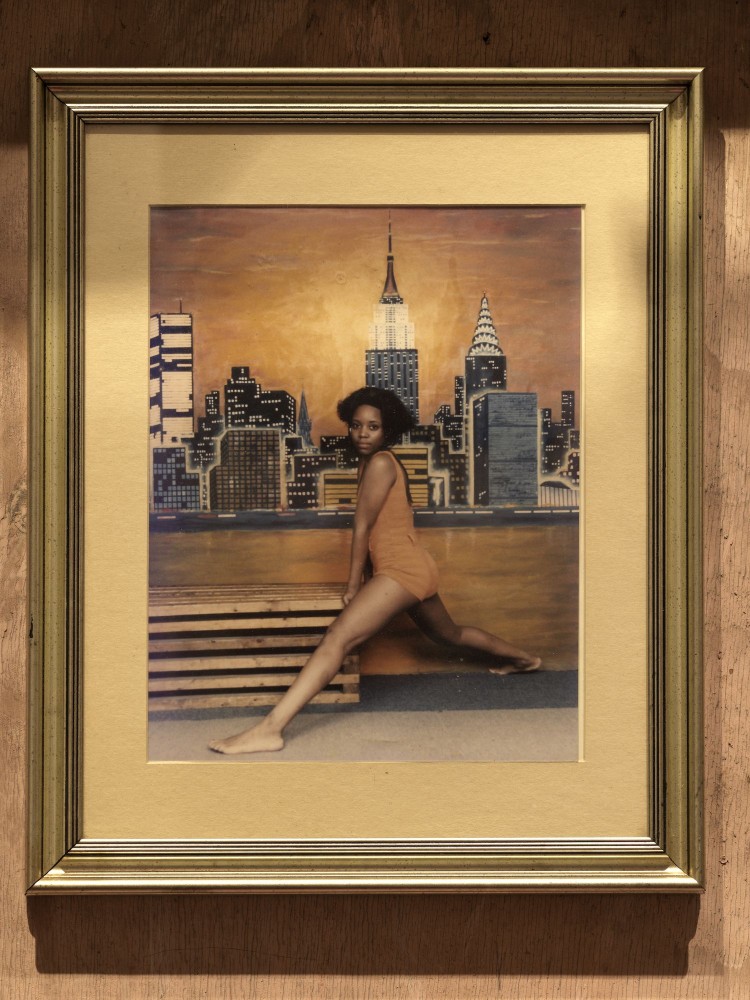

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Sugar Minott, 2020.

-

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Centerpiece (White Lane), 2020.

-

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Altarpiece, 2020.

-

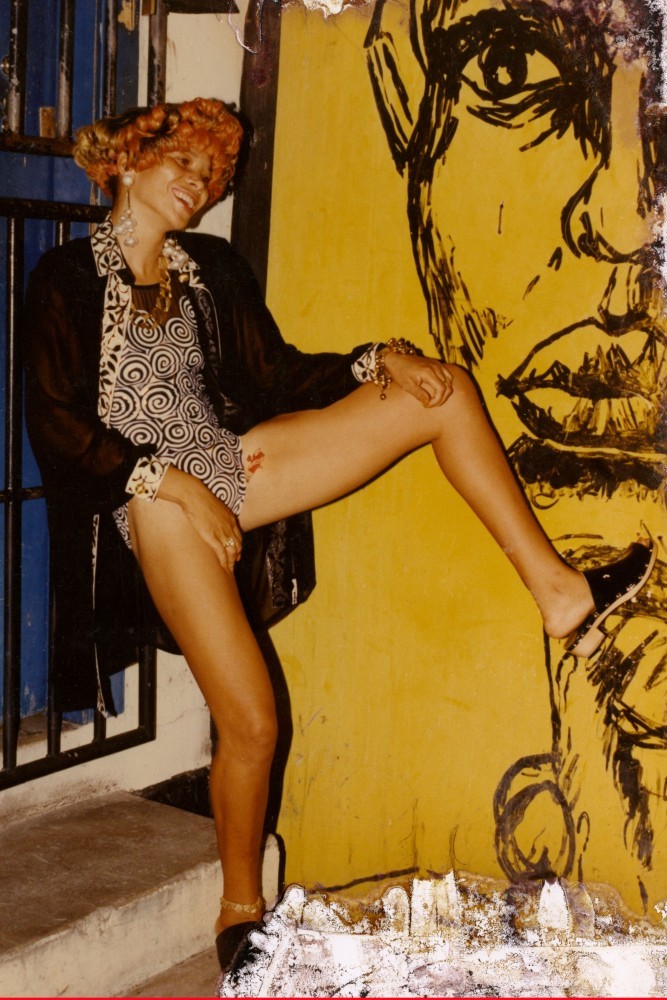

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Centerpiece no. 4, Untitled, 2020.

-

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Centerpiece (Matches Lane), 2020.

-

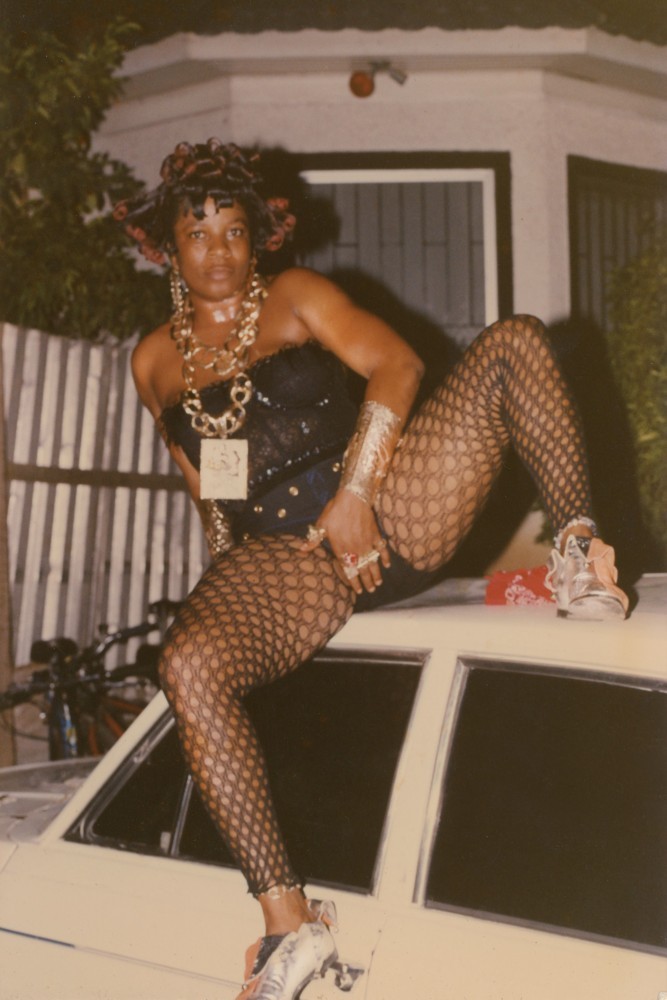

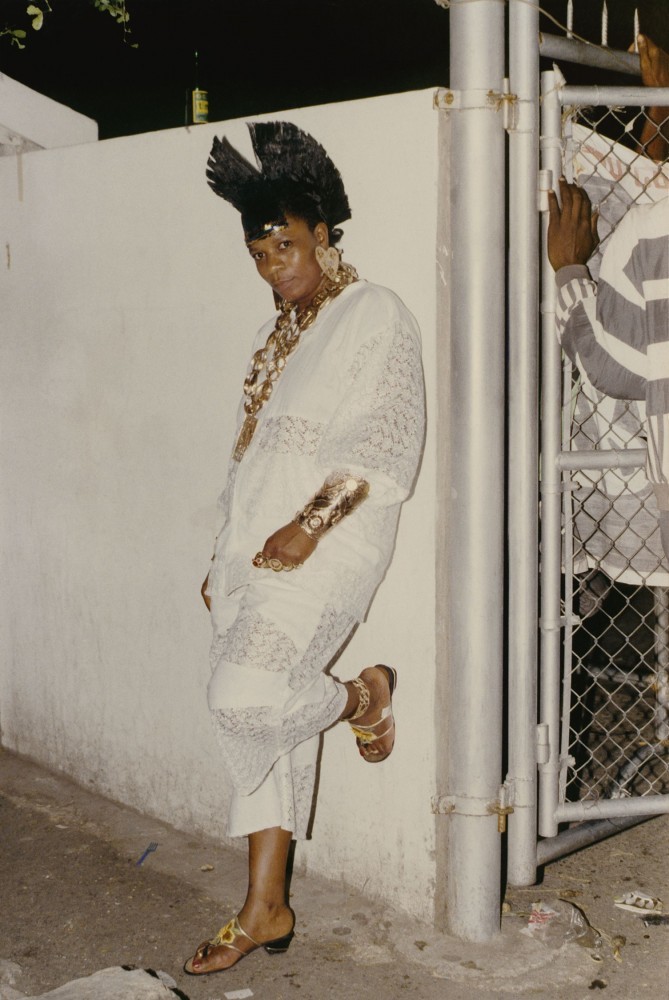

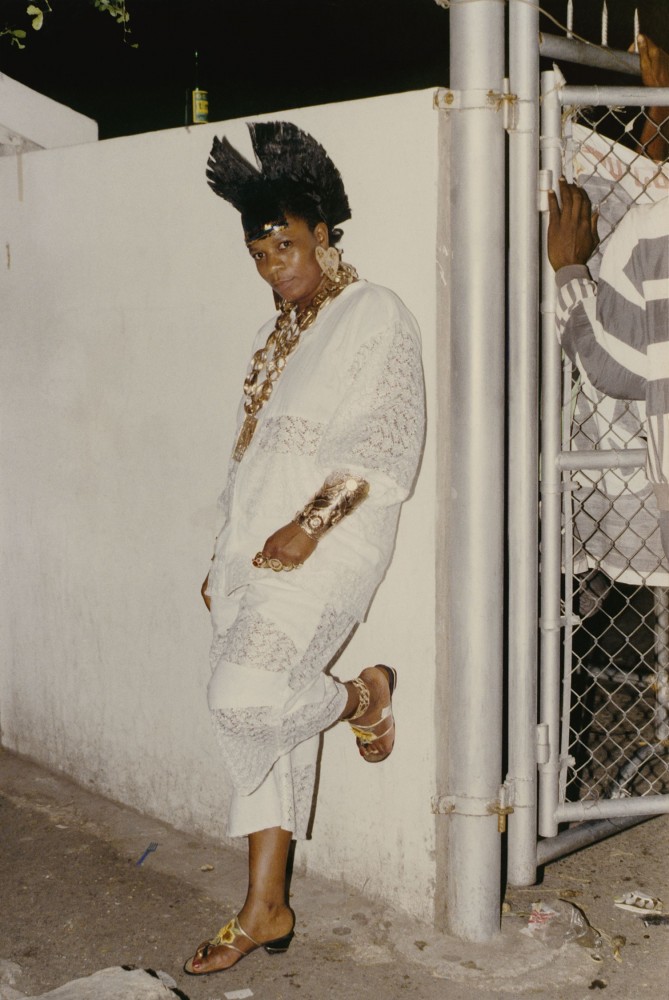

Photographer Unknown, chromogenic print, date unknown, No Gyal Can Test Archive, Bequeathed to Akeem Smith.

-

Vintage photograph, Detail of Akeem Smith, Centerpiece (Matches Lane), 2020.

When you had that original idea for the show, did it come from a place of feeling that the culture that you had grown up with was misrepresented?

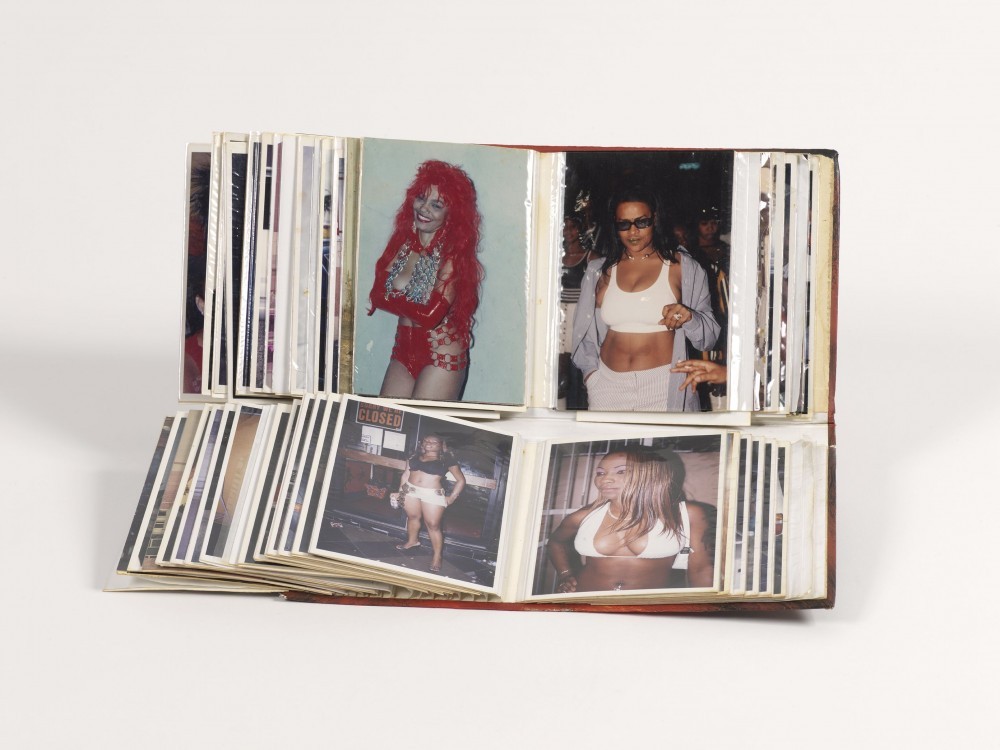

I think prevention is better than cure. In general dance hall is about the music, the sound, and all that. But I really wanted to also understand the visual loudness and why people of color are always considered loud, both sonically and visually. And I also wanted to put more focus on the women because the women were the nucleus of the parties, at least during the time that I grew up. It was their looks that really got the party going. The music is always there, but I was more interested in the anthropological aspect of it. This show is really for people in 2130 to see some sort of ancestry and familiarity. Sometimes we behave certain ways and we don't know why. I hope this project, in the future, can help people find answers within themselves. It could be someone's grandmother at the club in 1985, and they’ve never seen that before.

Did you ever go to any of these parties yourself?

I was too young to go, but I did have a birthday party once at a club that my grandmother used to co-own. It was called La Roose, in Portmore. Another spot was White Lane Ballfield where they used to have a bunch of parties in the street. There was no rivalry between venues or between parties. The rivalry was more in the looks and the crews. The first parties just happened in people’s backyards, and later they would evolve into other places. But they were all outdoor spaces because the sound system had to “boom.” Each DJ would bring their own sound system. People wanted to smoke and bust shots in the air, which is another reason to do it outdoors. Something that I really wanted to capture with the sculptures I made for the show is this in-between state: you could never tell if a place was like halfway done or halfway finished.

-

Akeem Smith, Memory, 2020: Single channel video, custom speaker system, color photographs, steel, score by Alex Somers.

Photography by Dario Lasagni. -

Akeem Smith, Social Cohesiveness, 2020: Three-channel video installation, score by Ashland Mines. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

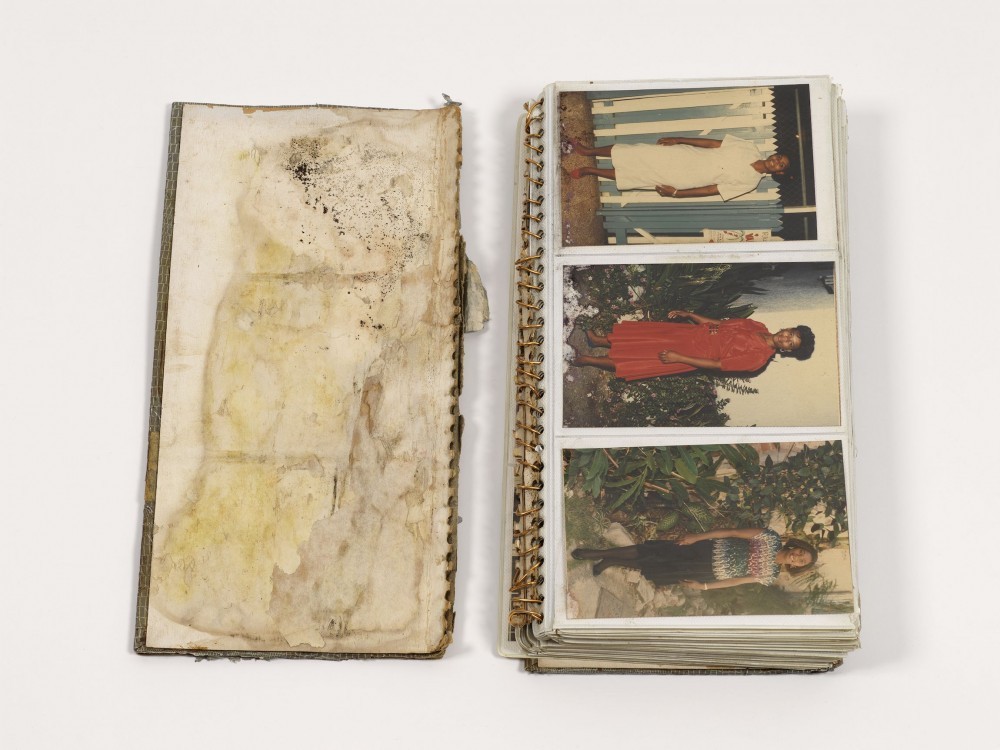

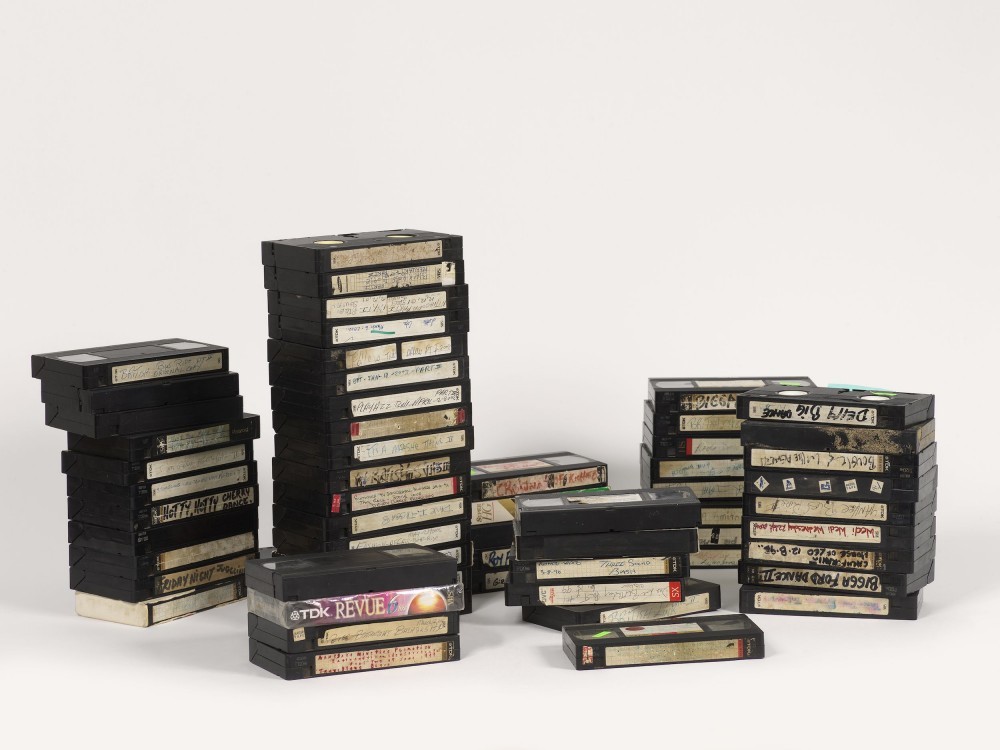

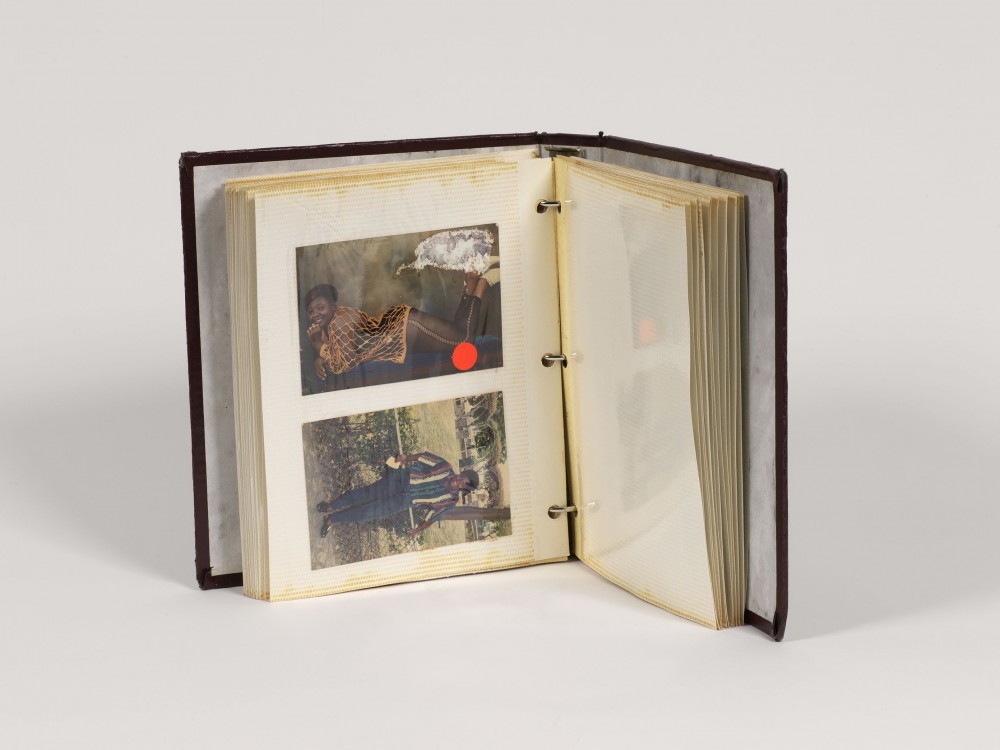

Akeem Smith, No Gyal Can Test Archive, Bequeathed to Akeem Smith.

What are some of the elements that you use for your sculptures?

In Jamaica there’s a lot of things that people do to their homes to represent climbing the economic ladder, so to speak. Making a grill for your gate, for your windows, or for your veranda, is one of those things. It’s called “Grilling your home.” We drove around in the neighborhood where I was raised in Jamaica, which is Waterhouse. I’m a party animal at heart, and so for me it was just weird to see all these old bar spots not being used anymore. I decided to buy them and break them down and use them for the show. We went to Portland where I have family, and whatever we saw — whether it was for sale, or if it was left on the side of the road — we broke it down and brought it over in a big container. None of the venues and none of the parties exist anymore. I think some people moved to America. Or they might’ve gone to jail.

-

Akeem Smith, Queens Street, 2020: Single-channel video, salvaged building material and fabric, breeze blocks, wood. Score by Ashland Mines. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

Installation View of Akeem Smith, No Gyal Can Test at Red Bull Arts New York, 2020. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

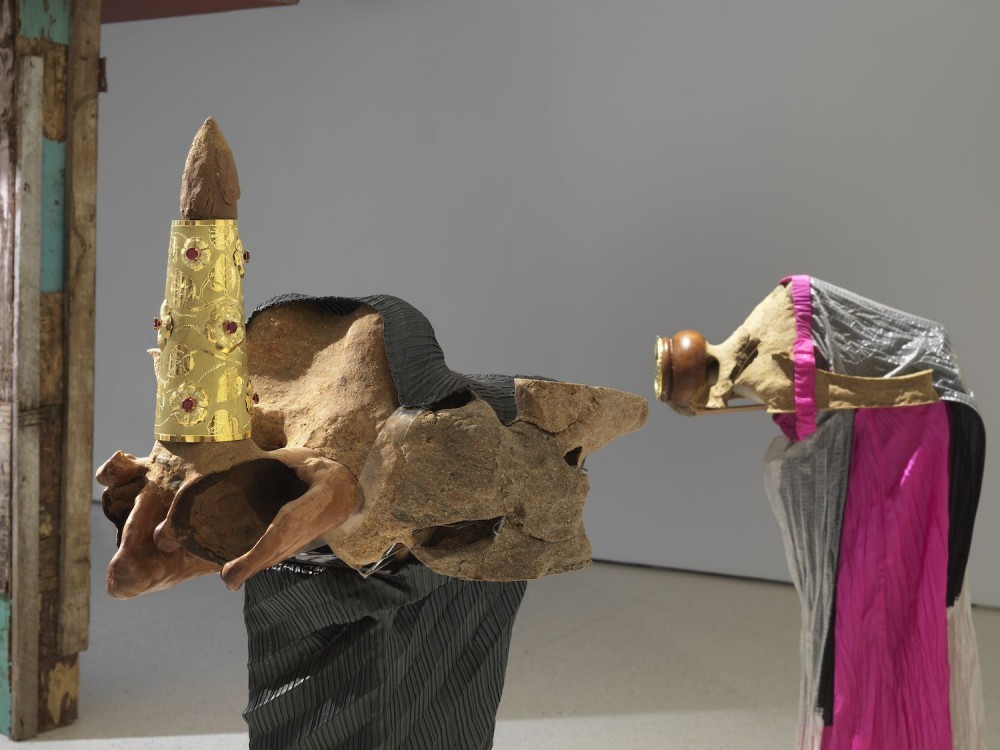

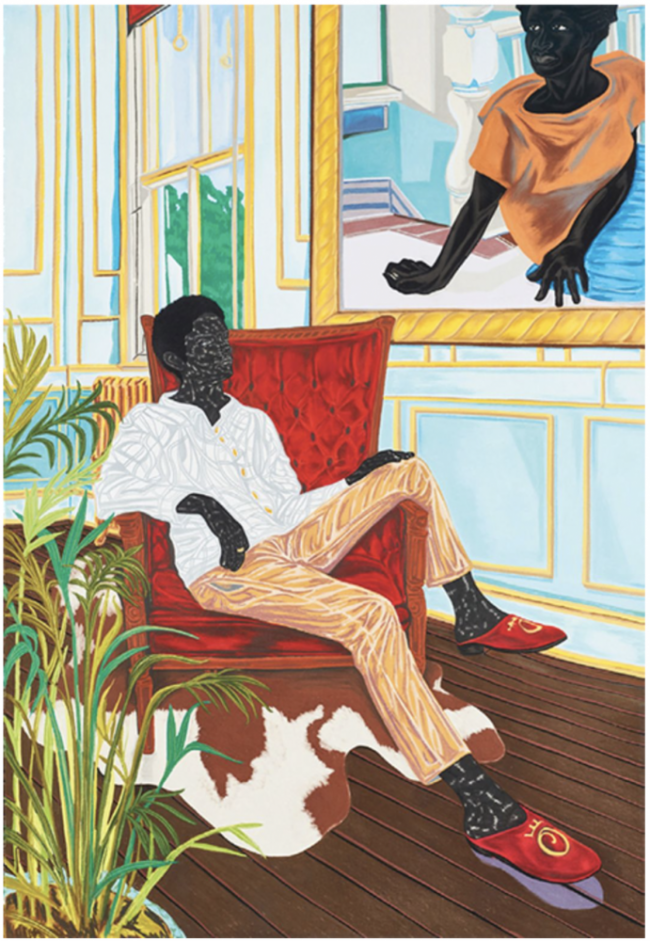

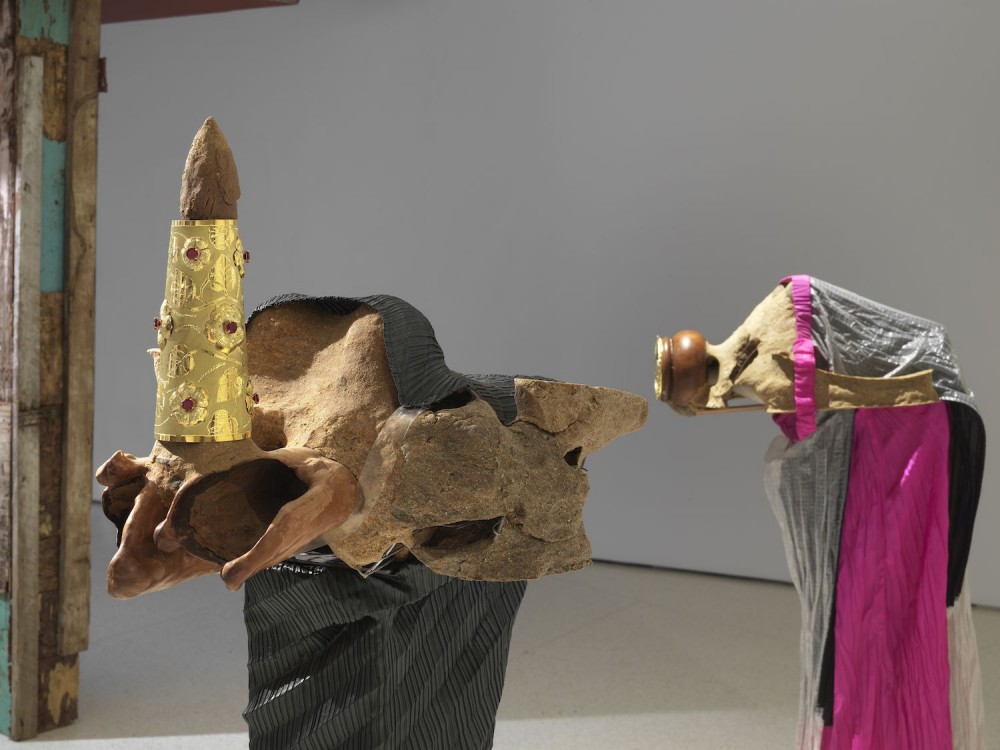

Detail of Akeem Smith in collaboration with Jessi Reaves,

Mannequin (with corset and expanded base) no. 3, Sandra Lee, 2003, 2020: Metal, sawdust, wood glue, wood, hardware, original

garments, custom jewelry. Photography by Dario Lasagni. -

Installation View of Akeem Smith, No Gyal Can Test at Red Bull Arts New York, 2020. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

-

Detail of Akeem Smith in collaboration with Jessi Reaves, Mannequin (with dress) no. 1, Sandra Lee, 2005, 2020: Metal, sawdust, wood glue, wood, hardware, original garments, custom

jewelry. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

Can you tell me about your collaboration with the artist Jessi Reaves for No Gyal Can Test?

We worked together on the sculptures. In the show the sculptures act as sort of reliquaries to dance hall culture in the sense that there's jewelry and outfits that were worn at the parties, and some of the jewelry was made by Brando — he used to date my grandmother and make the jewelry for everyone back then. There are some originals that he did back in the day, and then, there’s some remakes that he did for us. I'm not even like a recycle person, but there’s something about... I'll give you an example. Frankie Delessio, so his mom makes a tomato sauce, a marinara sauce, they Italian or whatever. Apparently, her mother-in-law made the best sauce, right, in this one jar. Ms. Carol hasn't washed that jar since her mother-in-law passed. She just puts new sauce in it. And since she hasn't washed it, the essence or whatever, some particle of her mother-in-law's sauce is in there, you know? That's sort of like how I make my sculptures, it starts from somewhere. It'll start from a specific object that I find at these spaces, in these communities.

Who were you most nervous about seeing the show, other than yourself?

The people that I've worked with, the original people that used to take the photos, the original video guys that used to film these events. There's been like a weird trust in me, honestly. I think everyone really trusts in me.

Text by Felix Burrichter.

Portraits by Christopher Tómas for PIN–UP. All other images courtesy the artist and Red Bull Arts.

Taken from the forthcoming PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.